Who Was Josephus?

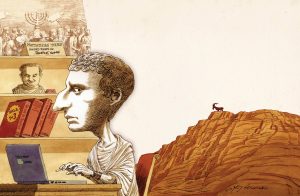

Two thousand years after his death, Josephus remains controversial, admired by some and loathed by others, as if the historic events he reported occurred just yesterday. His insights into the turbulent Second Temple period starkly contrast with the vague picture painted by rabbinic literature. Priest and rebel, military commander, shrewd politician and occasional fortune-teller, Josephus was an outsider in his own land but a Jew in exile. He wrote in Greek, his second language, and until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, his works provided almost the sole window into the esoteric, sectarian world of Second Temple Judaism.

Josephus’ testimony leaves us confused: is our view of ancient Jewish history, guided by rabbinic tradition, too narrow? Could this man whom many of us love to hate, whose writings reveal an inflated ego, actually have known the sages better than we do? Josephus’ Sadducean practices and Hellenistic ideas make it hard to accept him as a guide to the personalities quoted in the Mishna and Talmud. But it is even harder to ignore him. He was there: he spoke with the sages, witnessed the Temple rituals, and knew all the names, intrigues, and factional loyalties of the high priests during and after the Great Revolt, which ended in 70 CE. In contrast, the only high priests of the period mentioned by rabbinic sources are Joshua son of Gamla and Hananiah son of Hezekiah, and even they appear only in a religious context.

Jerusalem Aristocrat

Almost everything we know about the late Second Temple period, including about Josephus himself, comes from his writings – with all their biases. He provides uniquely graphic descriptions of life in the Roman Empire, including victory parades and military maneuvers. Yet this obsessive writer who was so desperate to present his own self-portrait for posterity, and who rubbed shoulders with the greatest leaders of his age, did not create a fawning, one-sided version of history. Josephus knew objectivity was a must for a historian, but he still gave vent to his feelings as to who was responsible for his people’s troubles:

However, I will not go to the other extreme, out of opposition to those men who extol the Romans, nor will I determine to raise the actions of my countrymen too high, but I will prosecute the actions of both parties with accuracy. Yet shall I suit my language to the passions I am under, as to the affairs I describe, and must be allowed to indulge some lamentations upon the miseries undergone by my own country; for that it was a seditious temper of our own that destroyed it; and that they were the tyrants among the Jews who brought the Roman power upon us…. But if anyone makes an unjust accusation against us, when we speak so passionately about the tyrants, or the robbers, or sorely bewail the misfortunes of our country, let him indulge our affections herein, though it be contrary to the rules for writing history. (Josephus, The Wars of the Jews, preface, pp. 427–8)

Ironically, Josephus’ avowedly unobjective historiography has provided his opponents with much ammunition.

Joseph son of Mattathias was born in Jerusalem in 37 CE, the year Caligula became emperor of Rome. Descended directly from the priestly family of Jonathan the Hasmonean, he received a broad Jewish and general education and grew up surrounded by mishnaic sages.

Remains of a first-century house in the sectarian community of Qumran, near the Dead Sea, an area frequented by the youthful Josephus in his search for spiritual direction

Inquisitive and independent, Josephus abandoned the luxuries of Sadducee society to study the religious sects in and around Jerusalem (including in the Judean Desert), trying to forge his own path through the labyrinth of divergent opinions in the late Second Temple period. When he was about twenty, having formulated his own religious views, he joined the Pharisees, the anti-Sadducee architects of rabbinic Judaism. Josephus describes himself as a brilliant student who discoursed with all the sages, but he mentions only one we know of – Simeon son of Gamliel, grandson of Hillel the Elder.

As a priest, Josephus knew all about Temple rites. In addition, numerous talmudic homilies appear in his synopsis of biblical history, proof of his close ties to rabbinic Judaism. He was also familiar with the Hellenistic Judaism of his day, which is not discussed in talmudic sources but exerted extensive, even international influence. The Herodian Jerusalem in which Josephus grew to manhood was among the largest, most cultured cities of the ancient Near East. Its Greek-speaking citizens would not have felt out of place anywhere in the Roman Empire. Furthermore, Josephus’ lineage guaranteed him respect as well as status, and he was assigned several important national missions, including a journey to Rome at age twenty-six, where he met Emperor Nero’s wife Poppaea.

Rebel and Traitor

Josephus was twenty-nine when the Great Revolt broke out in 66 CE. Appointed commander of the Galilee, he struggled to organize and fortify its Jewish communities. As a mere pawn in a much larger game, however, he could scarcely withstand Roman general Vespasian, who conquered the Galilee fortress by fortress in 67, sowing death and destruction.

Josephus was under siege in Jotapata for several weeks before Vespasian breached the walls of this Lower Galilee village. The last remaining fighters voted to commit suicide rather than surrender, but left to the last with one companion, Josephus changed sides. Describing the event in the third person, he claimed prophetic vision:

And just then he was in an ecstasy, and setting before him the tremendous images of the dreams he had lately had, he put up a secret prayer to God and said: “Since it pleaseth Thee, who hast created the Jewish nation, to depress the same, and since all their good fortune is gone over to the Romans, and since Thou hast made choice of this soul of mine to foretell what is to come to pass hereafter, I willingly give them my hands and am content to live. And I protest openly, that I do not go over to the Romans as a deserter of the Jews, but as a minister from Thee.” (Josephus, Wars of the Jews, III, viii:3)

The Roman destruction of the Jewish town of Jotapata didn’t stop Jews from living there. The Jerusalem Talmud confirms as much, and liturgical poems from Byzantine Palestine mention the priestly Miyamin family as residents of Yorfat, synonymous with the Hebrew Yodfat. The archaeological site of Jotapata today

Josephus’ defection recalls Rabbi Johanan son of Zakai’s escape from Jerusalem (Gittin 56). Both men deserted besieged towns already doomed to defeat. Like Rabbi Johanan, Josephus, by his own account – and we have no other – anticipated that Vespasian would become emperor, while expressing his scorn for the Zealots, whose infighting had destroyed Jerusalem. Like many sages, Josephus also argued that omens had foretold the destruction of the city and the Temple for years.

Josephus’ capture by the Romans began a new chapter in his life. As Vespasian’s protégé he became part and parcel of the Roman camp, supporting the general’s son Titus after his father returned to Rome as emperor. Josephus traveled all over the country with the Romans, fighting on their side (including in the siege of Jerusalem) and urging his fellow Jews to lay down their arms in this hopeless war. Understandably, the Jews branded him a traitor.

After sacking Jerusalem, Titus returned to Rome, taking Josephus with him. In another professional about-face, Josephus turned historian. His Wars of the Jews describes the Great Revolt to its bitter end at Masada, some three years after his departure from the scene. Josephus places passionate speeches in his heroes’ mouths. While not wholly factual, these orations express the political and religious views held by such personalities at the time, and were an accepted literary convention. A classic example is Eleazar son of Jair’s plea that his co-defenders choose death with honor over surrender and servitude on the eve of the fall of Masada. Obviously Josephus didn’t know exactly what Eleazar had said, but the speech summarizes the Zealot ideology with which the author was so familiar:

Since we, long ago, my generous friends, resolved never to be servants to the Romans, nor to any other than to God Himself, who alone is the true and just Lord of mankind, the time is now come that obliges us to make that resolution true in practice. And let us not at this time bring a reproach upon ourselves … for the laws of our country, and of God Himself, have, from ancient times, and as soon as ever could use our reason, continually taught us … that it is life that is a calamity to men and not death; for this last affords our souls their liberty and sends them … where they are to be insensible to all sorts of misery. (Josephus, Wars of the Jews, VII, viii:6–7)

Silver coin minted in Judea in 79 ce, depicting the conquest of Judea by the Flavian emperors. Titus’ head appears on the obverse, with an armed Roman soldier standing over a captured Jew on the reverse

Despite his outspoken opposition to the Zealots – and although he had found himself in a very similar situation and taken the opposite course – Josephus captures the pathos of their tragic end, preserving their heroism as an inspiration to future generations. No wonder he chose this stirring episode to end his book.

Written for the Diaspora

Titus kept his loyal protégé with him on his victory circuit through the cities of the Mediterranean Basin. Josephus recorded such festivities as the victory parade through Rome, which must have included the spoils of the Temple as well as many of his own less fortunate compatriots. Thanks to the patronage of the Flavian imperial family – Vespasian and his dynasty – Josephus was given an estate, a livelihood, protection from his enemies, and a new name: Titus Flavius Josephus. In the service of this family Josephus produced his life’s work, earning immortality by chronicling the dynasty’s campaigns and triumphs.

Josephus’ books vary in both genre and perspective. Around the year 80, some ten years after arriving in Rome, he published Wars of the Jews, the story of the Great Revolt and its failure. He devoted the next fifteen years to his magnum opus, Antiquities of the Jews, which traces Jewish history from its origins to his own day. In Antiquities, Josephus tried to lend proportion and depth to the story of his people, and to show that – the revolt notwithstanding – the Jews had a contribution to make to the world. In addition to these two great works, Josephus produced several shorter, more personal books: Life of Joseph, an attempt to defend his own name against Jewish and Roman attack; and his last work, Against Apion, a defense of Judaism.

Although Josephus wrote in Greek, his writings were translated into Latin by Christian monks who saw them as evidence of Jesus’ divinity. Illuminated manuscript of Josephus’ works

We don’t know which sources formed the basis of Josephus’ writings, though Antiquities mentions numerous Greek, Jewish, historical, and other works. In Wars of the Jews he relies mainly on his memory and military experience as a rebel and later as a member of the Flavian entourage. Here too Josephus borrows from other authors in describing cities, regions, and landscapes with which he cannot possibly have been personally acquainted, but he rarely cites his sources, perhaps to emphasize his own involvement in the events he relates.

Although first-century Rome was the world’s greatest metropolis, the city’s elite spoke Greek. Josephus likewise immersed himself in Hellenistic culture. His books draw heavily on Greek writers, particularly the historians who preceded him, and the format of his works closely resembles theirs. Yet he is never mentioned in Roman literature, and over time even his relations with his royal patrons seem to have cooled, although he continued to submit his books for their review before publication. Alone in Rome, Josephus devoted himself to his histories, determined to restore his people’s reputation and remake them as heroes in Roman eyes:

… There are not a few who are induced to draw their historical facts out of darkness into light, and to produce them for the benefit of the public, on account of the great importance of the facts themselves with which they have been concerned. Now of these several reasons for writing history, I must profess the two last were my own reasons also…. Upon the whole, a man that will peruse this history, may principally learn from it, that all events succeed well, even to an incredible degree, and the reward of felicity is proposed by God; but then it is to those that follow His will, and do not venture to break His excellent laws. (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, preface, p. 23)

Josephus’ personal circumstances undoubtedly influenced his portrayal of events. Many scholars have pointed to his depiction of Titus as a compassionate leader with no desire to burn the Temple. Yet Josephus occasionally denounces the crueler aspects of Roman society, including its emperors. The Romans and their leaders did not necessarily take offense at such descriptions; the spectacle of gladiators locked in mortal combat before a cheering crowd was a subject of pride, not shame, as far as Rome was concerned.

Josephus’ principal motive seems to have been to record the events of his time from a Jewish perspective, which for him meant blaming the Zealots for the tragedy that had befallen his people. This angle conveniently diminished Roman responsibility for the destruction in Judea, but Josephus would not have seen that as a distortion of the truth. Wars of the Jews opens with the armed struggle between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, both sons of Hasmonean queen Salome, and its emphasis on the disastrous nature of Jewish civil war continues right up until Josephus’ own era. Like the Talmudic sages, Josephus firmly believed that causeless hatred between factions ultimately caused the destruction of the Temple and the loss of Jewish sovereignty. But in marked contrast to the sages’ oblique criticism, Josephus details the savage infighting, betrayals, and assassinations that led to the fall of Jerusalem.

Officially, Josephus’ target audience was the Roman-Hellenistic world. He attempted to portray Jewish society as intellectually attractive and challenging, a culture worthy of Roman admiration. In fact, he clearly sought recognition and legitimacy from his own people, continually stressing that everything he did was for its own good. But he – and he alone – reports that the Jews rejected and maligned him. Josephus’ introduction to Wars of the Jews claims that he initially wrote this work for his own brethren in his mother tongue – Hebrew? Aramaic? – but no copies of this version have survived, and it may well have differed altogether from the one we know, which uses concepts and language familiar to the educated, Greek-speaking Roman reader.

Inevitable Defeat

Most of the speeches in Josephus’ books are voiced by Rome’s supporters among the Jews, and the notion of Roman invincibility is a recurring motif. Josephus saw the empire as divinely decreed. Here too, his opinions approximate those of our sages. As Rabbi Jose son of Kisma warns Rabbi Hanina son of Teradyon: “This nation has been crowned by Heaven” (Avoda Zara 18). From his stance outside the city walls, Josephus tried to convince the besieged Zealots of this truth:

That they must know the Roman power was invincible, and that they had been used to serve them … besides men may well enough grudge at the dishonor of owning ignoble masters over them, but ought not to do so to those who have all things under their command; for what part of the world is there that hath escaped the Romans? … And … fortune is on all hands gone over to them, and that God, when He had gone round the nations with this dominion, is now settled in Italy. (Josephus, Wars of the Jews, V, ix:3)

Josephus never justified Rome or condoned its excesses, many of which he himself documented. Unlike his peers, he did not attribute Rome’s power to its temperance or courage, concluding rather that the Romans had just as many moral failings as strengths. The very fact that their achievements defied reason was, in his view, proof that Rome ruled by God’s will, and incomprehensible as that may have been, rebellion was therefore unthinkable.

Josephus actually comes full circle. In his later works he hopes Rome will fall and Zion rise again, but by the hand of God, not of man. He ends, then, on a note not so distant from the dreams of redemption that inspired the Zealot leaders in the Great Revolt.

Josephus died in Rome around 100 CE, a respected Roman citizen. In the fourth century, Father Eusebius wrote that a statue of Josephus had been erected in the city after his death. His writings were known within Roman literary circles and later adopted by the Church, which saw them as confirming Jesus’ prophecies about the doom of Jerusalem and its evil ways. But until the tenth century, his works were lost to the Jewish world, either rejected or sunken in oblivion. Now, however, he remains almost the sole source for the Jewish history of his period.

Many have condemned Josephus as a traitor, but perhaps the truth of his message simply hurts. The revolt against Rome was indeed a disaster that could have been avoided, as many of our sages believed. To paraphrase Mark Twain, we can forgive someone who lies to us, but not someone who tells us the truth.