Charlotte “Lotte” Salomon was born just over a century ago to a wealthy Berlin family. Her father, a surgeon, pioneered mammography. Her mother committed suicide when Lotte was only nine, though the cause of death was hidden from her.

The Nazis came to power when Lotte was sixteen, after which she stopped attending school. Accepted nevertheless into the Berlin Academy of Arts, she left two years into her studies. The family fled Germany in 1938, and Lotte was sent to the South of France to live with her grandparents. Her grandmother tried to hang herself during the girl’s stay, and her grandfather subsequently informed her that six family members – including her own mother – had all committed suicide. Yet instead of succumbing to what seemed to be her grim destiny, Salomon declared, “I will live for them all!” Within two years (1941–2), she’d created over 730 notebook-size gouache paintings.

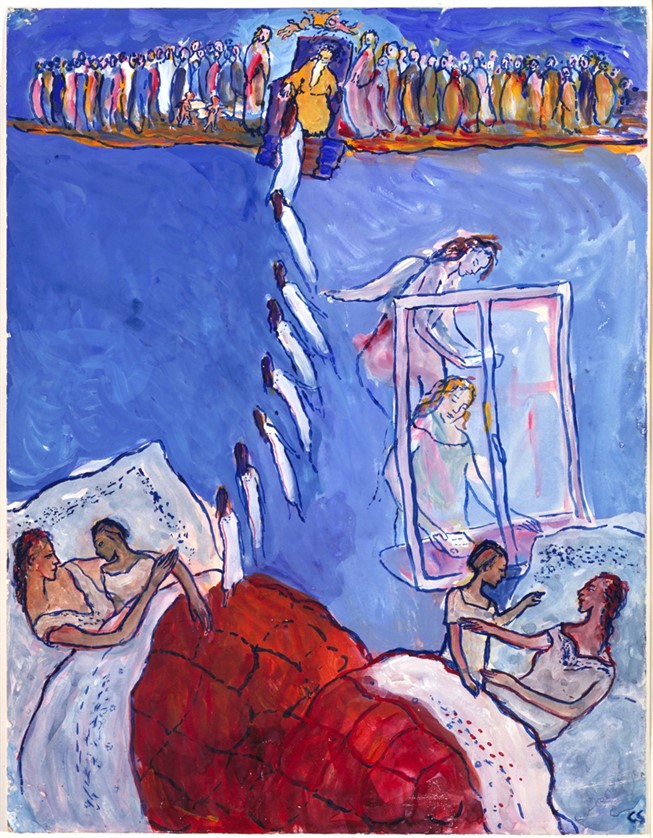

When her mother insinuated that she wanted to become an angel, Lotte asked her to leave for her a letter on the window sill. She was waiting for the letter the rest of her life

Working feverishly, Lotte chronicled the milestones of her life – her mother’s death, studying art in the shadow of the Third Reich, her relationship with her grandparents – changing her family’s names in her accompanying text and employing a strong fantasy element. Salomon started out using exquisitely bright colors, but in her final paintings she moved into darker, more morbid, almost violent shades, as if awaiting her impending fate. Humming as she worked, she tinkered with the paintings, rearranged them, added transparent overlays, and even suggested music to heighten their drama.

The painting shown here depicts a fictional Charlotte in bed with her sick mother, who tells her that soon she (the mother) will go to Heaven, become an angel, and leave her daughter a letter on her windowsill, raving about the after-world. Young Lotte is shown waiting for the letter at the window from which her mother jumped to her death. The text overlay asserts that “in Heaven, everything is much more beautiful than here on earth.”

Salomon wed in September 1943, but her marriage registration revealed her whereabouts to the Nazi authorities. As they intensified their search for Jews in southern France, she entrusted her drawings to friend Ottilie Moore. “Keep this safe,” the artist implored her. “It’s my whole life”. Arrested soon afterward with her husband, the pregnant Charlotte was gassed on arrival in Auschwitz.

Salomon’s father survived the war and subsequently received a package of nearly 1,700 of his daughter’s works, many of which can be found today in the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam.