The book of Esther is a strange bird in the biblical zoo: God is totally absent, at least in name; assimilation is never vilified, and much of the story takes place around Passover, though the festival isn’t even mentioned. These and other oddities made the Talmudic sages think twice before including Esther in the biblical canon (Megilla 7b).

Another of the book’s fascinating aspects is its historicity, which is both compelling – and questionable. So is Esther a historical document or a reworked pagan myth? Here’s the evidence as we see it.

India to Ethiopia

Chapter 1 of the book of Esther is the historical linchpin of the entire narrative. Here we meet Ahasuerus, who also appears in the biblical histories of Ezra and Nehemiah and is identified with the Achaemenid king Xerxes (r. 486–465 BCE).

The monarch who brought this dynasty from the relative obscurity of local kingship (rule by a shah under the thumb of the Empire of the Medes) to government by a “king of kings” (shahanshah in Persian) was Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 BCE). Jewish history praises him as the author of the Cyrus Declaration, permitting the Babylonian exiles from Judea to return to Jerusalem. Yet that decree is probably a particularistic rewrite of the first-ever declaration of human rights, the Cyrus Cylinder, for which the emperor is best-known.

A pluralist, Cyrus allowed his subjects to worship whomever and however they liked, so long as they harmed no one. Though the cylinder – housed in the British Museum – thanks the Babylonian god Marduk for Cyrus’ achievements, it also credits the great king with restoring religious freedom and rebuilding the ruined temples of all the deities worshiped in his empire. In exchange, he asked these gods to beseech Marduk’s favor on his behalf.

Cyrus’ successor was his son Cambyses II (r. ~530–522 BCE), followed by a second son, Bardiya, or possibly someone impersonating him. Bardiya was murdered by his cousin Darius I (r. 522–486 BCE), who married Atossa, Cyrus’ daughter. Their son was ostensibly the royal Persian hero of our story – Xerxes, better known to us as Ahasuerus.

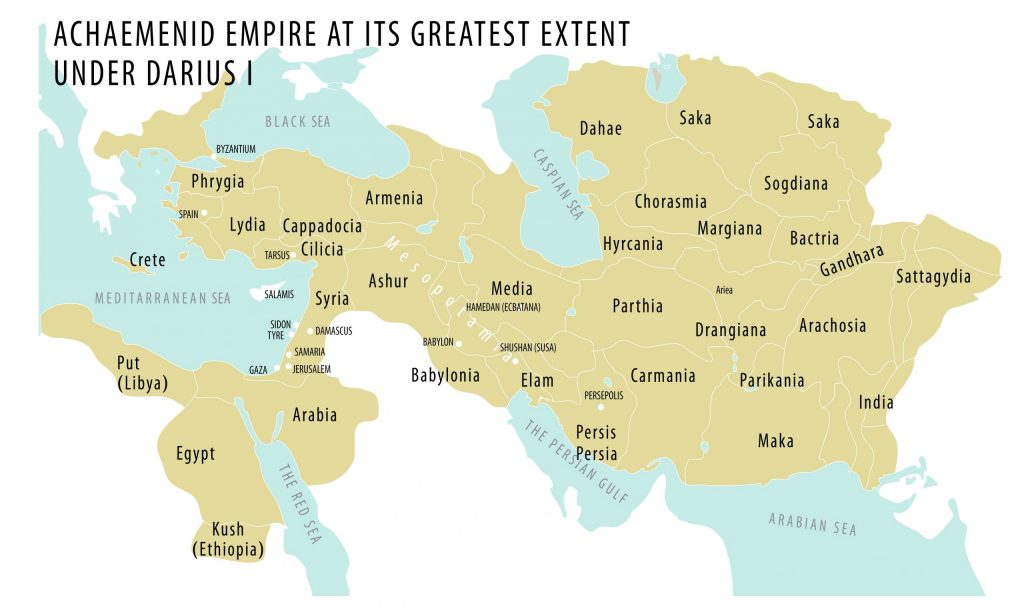

The family tree opposite includes a second, later Xerxes, but since he ruled only forty-five days, he can’t be the Persian king of the book of Esther, which spans several years. Ahasuerus’ empire extended from India to Ethiopia – as corroborated by maps dating from the Achaemenid Empire. On these maps, “India” refers to the Indus Valley – Hindush in ancient Persian – the easternmost satrapy of the empire. “Ethiopia” was its southernmost point, in today’s Sudan. The biblical text also states that Ahasuerus ruled 127 provinces. Yet that number is merely typological, used in the Bible and other ancient sources to denote a large sum, and thus doesn’t necessarily tally with the maps.

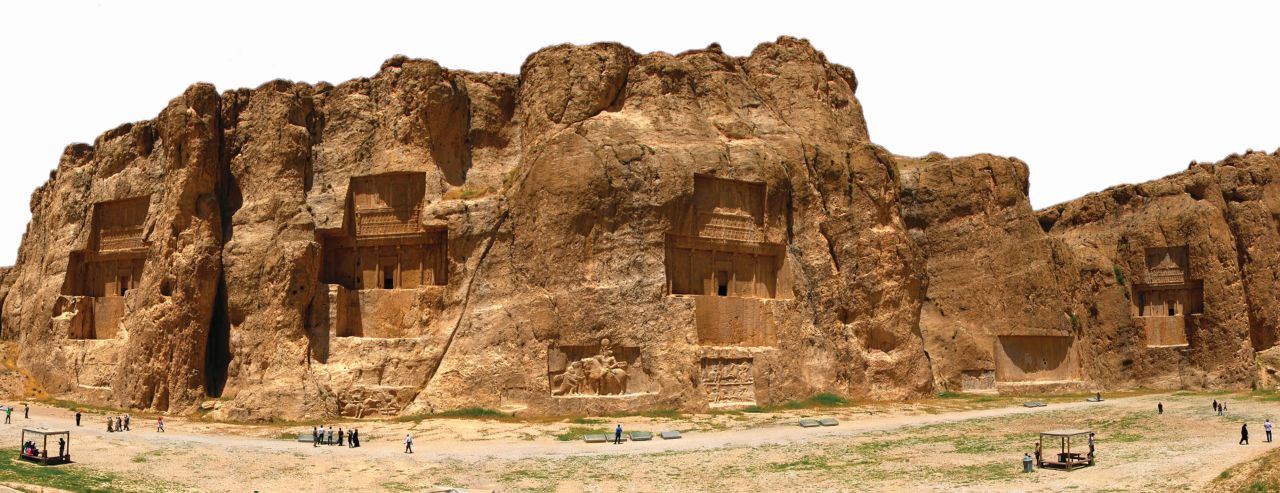

The book of Esther opens with a royal feast in Shushan, winter capital of the Achaemenid kings. Shushan corresponds to the city of Shush, in Iran’s Khuzestan Province. In antiquity, this area was dominated by the kingdom of Elam until the rise of the Persian Empire. When recounting the vassal states making up their empire, Achaemenid monarchs always started with Persia, Media, and Elam. The capitals of these provinces became Achaemenid capitals as well – Ecbatana (mentioned in Ezra 6:2 as Ahmeta, capital of Media and known today as Hamedan), Shushan or Susa (capital of Elam, appearing in Daniel 8:2), and Parsa (today’s Persepolis) the best known and most extensively excavated. Of all the ancient Persian capitals Shushan was apparently the most important and is the only one described by Greek historians.

The Cyrus Cylinder’s corroboration of the biblical narrative makes it one of history’s most sensational archaeological discoveries. Though the Bible claims only that Cyrus permitted the Jews to rebuild their Temple, the cylinder recounts that he allowed all his subjects to rebuild theirs

Foolish Monarch?

Achaemenid kings didn’t bother recording their feasts – perhaps they were too frequent to be noteworthy – but the biblical picture matches the ancient Greeks’ accounts of their enemy: the pomp and circumstance of the lavish palace with its marble pillars, silk-draped halls, gold and silver vessels, and excessive alcohol consumption.

Artifacts from the palaces discovered in Persepolis suggest how magnificent these structures originally were. Statue of a mythological beast from Persepolis

Ctesias, a Greek physician and historian who lived in the Achaemenid palace, complained that he was never allowed to drink wine from a clay jug like a civilized human being. The Persians, he wrote, drank exclusively out of silver and gold goblets, insisting their guests do likewise. Famed Greek historian Herodotus recalled that after one of Xerxes’ (Ahasuerus’) ships sank off the Greek coast, a local noble’s coffers were greatly enriched by the silver and gold utensils that washed ashore.

Herodotus also claimed that the Achaemenid monarchs set policy when drunk, then confirmed it while sober; or at the very least, if they happened to take a sober decision, it had to be ratified while they were inebriated. That might explain some of the book of Esther’s more unusual episodes, such as Ahasuerus’ drunken decree banishing Vashti (Esther 1:10–21) and his sitting down to drink after ordering all the Jews killed (ibid. 3:15).

Other incidents, too, become clear when Achaemenid language and customs are taken into account. For instance, the king orders the royal chronicles read before him (ibid. 6:1). How can the most powerful man in the Persian Empire not have known how to read? In ancient times, however, only professional scribes mastered the art of reading and writing. Royals were to stick to ruling and waging war.

Similarly, though he allows Haman to kill all the Jews and steal their property, Ahasuerus refuses payment for the favor. “The money is yours,” he says, “and the people, do with them as you please” (ibid. 3:11). Why this strange response?

Herodotus takes a psychological approach. He describes how Xerxes and his troops were grandly hosted by a wealthy man who offered to donate all his riches to the Persian war effort against the Greeks. Not only did Xerxes decline the generous contribution, but he insisted on paying the fellow an astronomical sum rather than be indebted to anyone for his hospitality. Later, this would-be benefactor begged the emperor to exempt one of his five sons from the draft (so there’d be someone to tend to him in his old age). Not only did Xerxes rail at the man’s ingratitude, he had the son cut in two and marched his army between the halves of the corpse! Ahasuerus may have likewise preferred to owe Haman nothing and therefore refused his bribe.

Then there’s the linguistic explanation, which is less dramatic. In ancient Persian, “I did” was usually expressed as “done to me,” “you’ve eaten” as “eaten to you,” and “you’ve given” as “given to you.” Thus, when the book of Esther translates the king’s words from Persian into Hebrew, “the money is yours” – literally, “the money is given to you” – really meant “you’ve given the money,” and Achasuerus was accepting the gift, not refusing!

No Recourse

The book of Esther portrays Ahasuerus as easily manipulated by women. So too, Greek historians depict Xerxes as a shameless skirt-chaser, adding that women heavily influenced all the weighty decisions taken by the men of his day.

One of Herodotus’ most hair-raising anecdotes relates how the king’s first wife, Amestris (whom some identify with Esther), wove her husband a dazzling cloak. Delighted with the garment, Xerxes wore it for a rendezvous with his lover, Artaynte (who also happened to be both his daughter-in-law and his niece), during which he rashly promised her anything she pleased. Artaynte requested the cloak.

Knowing his wife would be insanely jealous if she saw another woman draped in her gift, Xerxes begged his mistress to choose something else. He offered gold, cities, even her own army, but she turned them all down. Defeated, Xerxes handed over the cloak, which his paramour then flaunted all over the palace.

This fortress, nicknamed “the chateau”, was built by French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan in the late 19th century to house his staff during the extensive excavations of the vast, ancient city of Persepolis. Local lore later transformed it into the palace of the Persian kings

Amestris waited for the right moment to extract her revenge. Finally, at the king’s birthday party, when he was duty bound to grant all petitions, she asked that her husband place Artaynte’s mother in her power. This unnamed woman had also been pursued by Xerxes. To win her over, he’d even married off his son Darius to her daughter. Artaynte’s mother had rejected the king, however, so he’d transferred his affections to the daughter. Nonetheless, Queen Amestris blamed her original rival for the king’s infidelity and punished her with a fate worse than death, mutilating her beyond recognition (Herodotus, The Histories, trans. A. D. Godley [Loeb Classical Library, 1920], book IX, ch. 112).

So there we have it: a king at the mercy of his court’s many women, and edicts that, “written in the king’s name, and sealed with the king’s signet ring, no one can revoke” (Esther 8:8). Even without a writ or official seal, Xerxes couldn’t break his word to either Artaynte or Amestris. Indeed, Greek history is full of kings’ misguided promises and the epic adventures they set in motion.

What’s in a Name?

We’ve made the case for the book of Esther as Persian history. Now, in true Purim style, we’ll turn everything upside down and argue the opposite.

Though it does sound like Esther, the name Amestris could almost as easily be construed as Vashti – the letters vav and mem are interchangeable in word-loans between languages, and an extra alef can always be explained away (think how Spanish – as well as Persian – speakers tend to add “eh” before and after the word “stress”). But Amestris was certainly not Vashti, Ahasuerus’ first wife, because she remained firmly in place until well after her husband’s death (Ctesias, fragment 15), holding sway during the reign of his son Artaxerxes (465–425/4 BCE). And apart from their vaguely similar names, nothing supports the assumption that Amestris was Esther either.

Amestris was Persian, the daughter of Otanes (Hutāna in Persian). Far from being a Jewess elevated by winning a Miss World contest, she came from a family born to rule – one of six noble clans that had helped Darius save the Persians from reverting to Median domination. Oddly enough, her father and sister both figure prominently in that story, in roles not unlike those of Esther and Mordecai in the biblical narrative.

Speaking of Mordecai, the name Marduka – presumably derived from the chief deity in the Babylonian pantheon, Marduk – appears in Iranian sources from the time of Xerxes. Yet several royal officials were so called, and none occupied senior positions of the sort held by the biblical Mordecai. Most were minor clerks and tax collectors, their names featured on unexciting ostracons (inscribed clay fragments) issued as receipts for tribute in the form of grain or flour.

“Esther” too suggests a Babylonian deity: Ishtar, goddess of love and fertility. All over the ancient Near East, such female divinities were identified with the myrtle plant, hadas in Hebrew. Hence the queen’s other name – Hadassah (Esther 2:7). None of this, interesting though it is, makes Esther any more of an actual historical figure.

One of the most seemingly authentic elements in the story is the name of the king, Ahasuerus, and his identification with Xerxes. However, in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Bible, dating from the third or second century BCE), the king around whom the book of Esther revolves is called Artaxerxes, Xerxes’ son and heir, who appears in the biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah as Ahasuerus’ successor, Artahshasta. True, this rendering could just have been a mistranslation of Ahasuerus, which sounds more like Artaxerxes than like Xerxes. After all, the Septuagint was written not in Persia but in Egypt, and at least two hundred years after the events described in the book of Esther. Yet subsequent, Persian retellings of the narrative don’t mention Ahasuerus or Xerxes either. Take Ardashir-nāmah, a Judeo-Persian poem written by Mowlānā Shāhin-e-Shirāzi in the 14th century. This work refers to the king as Ardashir, a Middle Persian version of the ancient Persian name Artaxšaça, which is rendered in Hebrew as Artahshasta and in Greek as Artaxerxes. Ardashir was also the name of the founder of Persia’s Sassanid dynasty, which ruled from the third to seventh centuries – long after our story. Shirāzi’s poem thus interweaves Iranian myths and history with the biblical tale of Esther and Mordecai.

Furthermore, in the Judeo-Arabic translation of Esther, used in the Syrian community of Aleppo, the king is Alazdashiri – a name resembling Ardashir more than Xerxes.

In summation, later and non-Persian traditions seem to identify Ahasuerus with Artaxerxes.

Haman’s ethnic identity varies too in the different accounts. In the Bible he’s the Agagite (Esther 3:1), a descendant of the Amalekite king Agag, whom the first Israelite monarch, Saul, failed to eliminate as commanded (I Samuel 15). Accordingly, the story comes full circle when Mordecai, from the direct line of Saul, finishes the job by bringing down Haman and his sons.

The Greek renditions of the book of Esther – both the Septuagint and the more or less contemporaneous but less famous Alpha translation – call Haman Bougaios, possibly derived from baga, the ancient Persian word for “god.” One additional passage appearing in the Septuagint (which has its own embellishments of the story of the Megilla) even describes him as Macedonian, i.e., Greek in origin.

The Birth of Darius

Remarkably, there are no early Judeo-Persian versions of the book of Esther. Jews begin appearing in Iranian literature only from the third century CE, and an Iranian adaptation of the Megilla was composed only in the 20th century after the Islamic Revolution, when it went viral in the country’s anti-Semitic circles. The unscrupulous Mordecai of this story persuades Ahasuerus to depose the innocent Vashti and replace her with Esther. The Jewish couple then conspires to bring about an “Iranian Holocaust,” in memory of which the Jews celebrate an annual “Persian genocide” festival!

Yet one early Iranian work does bear striking similarities to the book of Esther. In this brief tale, Darius himself narrates how he became king after ousting a usurper of the throne following the death of Cambyses.

Herodotus’ longer Greek version is much richer in detail and in parallels to the Megilla. The author recounts how Cambyses son of Cyrus – or Kanbuzi son of Koresh in Hebrew – sent an assassin to dispose of his brother Smerdis (Bardiya in Persian) while the king was busy crushing a revolt in Egypt. A dream had foretold that “Smerdis” was to dislodge Cambyses from his throne. Unfortunately, this villain wasn’t the faithful brother of Cambyses, but Smerdis the Mede. The king realized as much only on his deathbed. Gathering the Persian chieftains around him, he swore them to prevent the Medes from regaining power.

The book of Esther’s drama inspired countless artists over the generations. Ahasuerus extends his scepter to Esther, Jacopo da Sellaio, tempera on wood panel, 15th century, Italy

Meanwhile, the messenger sent to assassinate Smerdis had done his job, and the throne fell into the clutches of Smerdis the Magus – the Mede – masquerading as Cambyses’ deceased brother. Only the assassin knew the real Smerdis was dead, and he had no reason to incriminate himself by revealing the truth. Smerdis exploited his fleeting reign to inflict enormous damage on Persian rule, even triggering an imperial crisis by granting exemptions from the draft and tax breaks to his non-Persian subjects (just as Ahasuerus gives his provinces a discount in celebration of Esther’s coronation).

It was a Persian nobleman named Otanes who first suspected that the king was an imposter. After all, from the moment he’d ascended the throne, Smerdis had never left the palace or allowed himself to be seen by any Persian (who might have known what the real Smerdis, son of Cyrus and brother of Cambyses, looked like). Otanes decided to put things to the test.

By coincidence, Otanes’ daughter Phaedyme had been married to Cambyses; therefore, together with his other wives, she passed to his successor. Otanes sent a messenger to Phaedyme asking whether it was really Smerdis son of Cyrus sleeping beside her in the royal bedchamber.Much as the hero and heroine of the book of Esther communicated extensively by messenger in chapter 4, Phaedyme sent a message back: Inasmuch as she’d never actually laid eyes on Smerdis prior to her husband’s death, she couldn’t confirm the new king’s identity.

Otanes then asked her to consult Atossa, daughter of Cyrus and sister of Cambyses and Smerdis-Bardiya, who would later become the wife of Darius and the mother of Ahasuerus. Surely Atossa would recognize her own brother. But Phaedyme couldn’t contact her, as the king had scattered his harem, setting up each wife in a separate abode.

Otanes’ suspicions grew, and his next message to his daughter echoed Mordecai’s warning to Esther:

Daughter, it is due to your noble birth that you should run any risks that your father bids you face. (Herodotus, book III, ch. 69, p. 89)

Otanes instructed Phaedyme to wait until her husband was sleeping at her side, then check whether he had ears. If he was the wrong Smerdis, the Magus, his ears would be missing, having been lopped off by Cyrus as punishment for some crime.

As Esther aficionados might expect, the dutiful daughter replied through her faithful messenger that this mission would mean risking her life, but she’d do it anyway. When it was her turn to lie with the king, she waited until he was fast asleep, then inspected his head. Sure enough, no ears.

Do the biblical Haman and his conspiracy have any historical basis? Esther accusing Haman, Ernest Norman, oil on canvas, 1888

Otanes promptly recruited seven valiant Persians, and together they slaughtered Smerdis the Magus and all the other Medes in the palace. Although Darius was the last to join this strike force, he was crowned king. The other six warriors were granted substantial benefits, including the right to enter the king’s presence without permission (which we know was limited to a privileged few). Of all the king’s wives, only women from these six families could serve as main wife or queen. Darius wed his cousin Atossa, while his son Xerxes married Otanes’ other daughter, Amestris.

The Persians massacred the Medes on 10 Tishrei, 522 or 521 BCE, and celebrated the anniversary of this victory until at least the fourth century. Every year on that date, Zoroastrian priests (known as magi) were forbidden by tradition to leave their homes.

Both the book of Esther and the story of the rise of Darius borrow from ancient Near Eastern New Year myths associated with the equinoxes or the winter zenith. Like these legends, both narratives include an existential threat to the nation (or the entire world). In the Megilla, this danger takes the form of Haman’s plot against the Jews, and in the tale of Darius, it’s the Medes undermining the Persians. Then, in said myths, either a god or his representative on earth – the king – must be vanquished. But as civilizations are generally reluctant to encourage regicide, it’s the second in command (Haman the vizier) or an imposter (Smerdis the Magus) who is disposed of. The festival celebrating this defeat of evil is often accompanied by rituals overturning the social order, such as drunkenness.

Yet the Esther and Darius narratives uniquely revolve around a fair maiden who marries the king and saves her people with the help of a relative stationed at the king’s gate.

Did It Really Happen?

The above historical parallels are both fascinating and confusing. All reflect the same Persian period, culture, customs, characters, and expressions. But there’s no hard evidence of the events of the biblical book of Esther in any contemporaneous Persian sources or later traditions. Instead, there are more than a few outright contradictions. Did the story of Esther and Mordecai happen as recounted, did the biblical author exaggerate, or is it complete fiction? Perhaps the question is irrelevant. Like all saturnalias, Purim is an opportunity for organized chaos, for defying social conventions for just one day – so why give up on that?

Further reading

Thamar Eilam Gindin, The Book of Esther Unmasked, Zeresh Books, 2016

Vera Basch Moreen, In Queen Esther’s Garden: An Anthology of Judeo-Persian Literature (Yale University Press, 2000)