Staying Alive

The Holocaust challenged the humanity of its victims. Difficult as it was to survive physically, spiritual and emotional survival was virtually impossible. Many Jews abandoned their moral values in order to stay alive, although many others credited their survival to altruism and faith.

Courageous Jewish leaders offered crucial coping mechanisms during those terrible times. This article focuses on four such figures, each representing a different approach to spiritual survival.

God Hides His Face

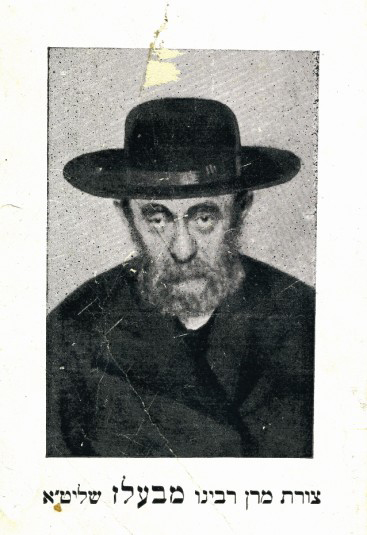

Rabbi Aharon Rokeach (1880–1957), the Belzer Rebbe, succeeded his father as leader of the Belz Hasidic dynasty in 1926. Rabbi Aharon’s anguished personality represents one of the most powerful expressions of the human tragedy of the Holocaust. All six of his children perished in Nazi Europe; his followers claimed that he never mentioned them publicly, but their deaths undoubtedly weighed heavily on his soul. The Belzer Rebbe became renowned but controversial, largely due to his flight from Hungary to Palestine in January 1944 and the famous sermon given by his brother, Rabbi Mordechai of Bilgoray, just before their departure. In this address, a censored version of which was later published by his disciples, Rabbi Mordechai promised in his brother’s name that Hungarian Jewry would survive the war unscathed, for the righteous rabbi would pray for his flock once he reached the land of Israel. Several months later, the destruction of Hungarian Jewry moved into high gear. Nearly 500,000 Jews, including refugees from Poland and Slovakia, were exterminated in the Nazi death camps.

Rabbi Aharon Rokeah was known for his ascetic habits, ability to function without sleep, and long hours immersed in study and prayer. He was only forty-six when he stepped into his father’s shoes as the Belzer Rebbe in 1926. Portrait from 1929

Some blame the Belzer Rebbe for the death of his followers, since he instructed them not to immigrate to Palestine. The current rebbe, Rabbi Mordechai’s son Yissachar Dov, addressed this criticism in a sermon published in January 2003:

There are two ways in which the Almighty can hide His face. One is to simply conceal from the spiritual leader, the tzaddik, what the future holds. But there can also be something worse – when the Almighty shows the tzaddik a good outcome, the opposite of what will happen. That is what we call concealment within concealment. (Aharon Perlov, The Sanctity of Aharon, p. 363 [Hebrew])

In short, it was the hidden face of God that had deluded the Belzer Rebbe regarding Hungarian Jewry’s fate.

Rabbi Aharon’s flight actually began when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. He was constantly on the move in search of a safe haven, occasionally assuming a false identity. Traveling from Belz through Peremyshliany (Galicia), Nowy Wiśnicz, and Kraków before settling in the Bochnia ghetto, he encountered horrific sights at every turn, which worsened his failing health. A dangerous rescue operation succeeded in smuggling him over the Polish/Hungarian border via treacherous routes from Bochnia to Budapest, where he eventually boarded the Orient Express for Istanbul.

Hope in the Darkness

Despite the controversy surrounding the Belzer Rebbe’s leadership, he tended to his flock even as he fled. Rabbi Moshe Halevi Steinberg, rabbi of Peremyshliany (and later of Kiryat Yam, Haifa), described Rabbi Aharon’s concern for his welfare and that of his elderly grandfather Rabbi Shemaya when they met in 1941. Rabbi Steinberg also recalled how the Jews of Peremyshliany flocked to the Rebbe’s court in times of distress.

The calm before the storm. The Belzer Rebbe with his some of his leading followers before the war forced him into flight, disguise, and exile. Legend has it that he shaved his beard to conceal his identity while traveling, and secluded himself on arrival in Palestine until it grew back

The Jews of the town gravitated toward the synagogue opposite the rebbe’s home, hoping the great rabbi’s merit would protect them. From every street and alleyway, people ran to the synagogue for “shelter,” bundles on their shoulders….

As soon as we got there, we were invited into the rebbe’s study. He was tense and very serious, lost in thought, sighing deeply every so often. Unable to sit still, he paced the room, gartel in hand. Time flew by, and it was already half past noon. I was asked to urge the rebbe to begin the daily prayers, as it was extremely late in the day. “It is time to pray,” I said in a trembling voice.

“The heavens do not heed my prayers” declared the Rebbe. He stood up and faced me. “You must leave Peremyshliany immediately….”

The rebbe’s words convinced me, and I agreed to follow his advice. He took both my hands in his and we stood there, face to face, for another quarter of an hour or more. He spoke to me, but I was too distraught to absorb what he was saying. Just one sentence stayed with me, although I couldn’t understand why those were his parting words: “If rain should fall, know that it is blessed rain.” (Mishberei Yam [Jerusalem, 5752/1992], For Your Miracles That Are with Us Each Day, pp. 127–8)

Similar stories have been collected from each stop along the rebbe’s escape route. Thousands hung on his every word, seeking his counsel, blessing, and salvation. His sense of having disappointed his followers haunted him until his dying day, sending him into seclusion after the war. At the same time, a burning sense of responsibility drove him to rebuild Belz from scratch.

Dying with Honor

While the Belzer Rebbe tried to be a pillar of strength for all Jews in distress, Rabbi Menahem Ziemba (1883–1943) grappled with a very different issue –maintaining some kind of Jewish dignity and pride amid the seemingly futile struggle for Jewish survival. Ziemba shunned the rabbinate for years, devoting himself to Torah studies as long as his father-in-law could support him, then turning to trade. He became acting rabbi of Warsaw only after the Nazis’ arrival, when his scholarship combined with his readiness to confront the authorities and speak up on behalf of his people to make him a key figure in the ghetto. Numerous testimonies describe Rabbi Ziemba’s pivotal influence on the decision to revolt. He insisted that even if the rebellion saved no Jewish lives, it would restore Jewish national pride and dignity.

Rabbi Ziemba’s immediate relatives all perished before the Warsaw ghetto uprising, making his support for the revolt purely idealistic. His wife and two young daughters were sent to Treblinka in the first transport of Jews (in August 1942), and his son and daughter-in-law, their five sons, and his daughter and her husband were all sent to Majdanek. Another son and a married daughter, along with her husband and two children, perished as well. His entire family eradicated, Rabbi Ziemba continued to preach in the ghetto, voicing the emotions that sustained him in those bitter days:

There are different ways of sanctifying God’s name by martydom. If, as in Spain or during the Crusades, Jews were now being forced to forsake their religion and could save themselves by agreeing to be baptized, the mere fact of our deaths would sanctify His name. Maimonides even states – and Jewish law follows his opinion – that the death of any Jew who is killed just because he is a Jew is a martyr’s death. But today, the only way to sanctify His name is by armed resistance! (quoted by Hillel Seidman in The Warsaw Ghetto Diaries, p. 236)

Some deny that Rabbi Ziemba supported the uprising. According to several of his students, violence contradicted his philosophy. Yet they were not with him during the war and therefore cannot claim to know how he reacted to the appalling circumstances in the ghetto. Rabbi Ziemba’s nephew, Rabbi Abraham Ziemba, testified that the Jews’ generally submissive behavior was anathema to his uncle, who urged defiance of the Nazis.

Honorable surrender. Rabbi Menahem Ziemba’s outlook evidently triumphed in the end; for many Jews, the Warsaw ghetto uprising represents a spark of Jewish heroism in the dark humiliation of the Holocaust. Jewish women captured at the end of the revolt

While the Belzer Rebbe submissively accepted the horrors of the Holocaust and tried to comfort his fellow Jews, Rabbi Ziemba refused to capitulate to the inevitability of his situation. He strove for change, whether actual or only in intent, convinced that how Jews died, for what and why, would make a difference in the future.

Knowledge – the Essence of Life

A similar conviction inspired a quite opposite leader, Rabbi Dr. Leo Baeck (1873–1956). Years before the Holocaust, this highly respected Reform rabbi foresaw the dangers of the Nazi regime and fought its rise with all his might. In January 1943, Baeck was deported to Theresienstadt with thousands of other German Jews. Though offered exit papers more than once, he refused to abandon his congregation. Nor did he avail himself of opportunities to save many of his relatives; three of his sisters were murdered by the Nazis. Baeck had served as a German chaplain during World War I, and his life’s work focused on the significance of Judaism in the context of Western philosophy. His best-known book, The Essence of Judaism (1905), epitomized his efforts to create a modern Jewish society deeply rooted in the achievements of west European culture.

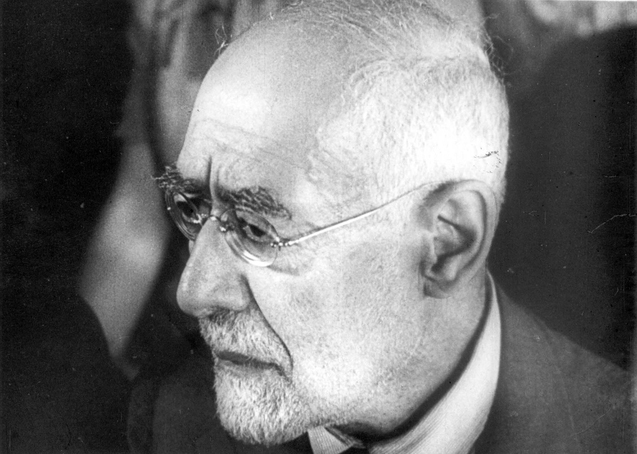

Jewish wisdom and tailored elegance in the bowels of hell. Rabbi Dr. Leo Baeck as a prisoner in Theresienstadt

Baeck’s sermons in Theresienstadt attempted to restore human dignity amid the camp’s crowded and unsanitary conditions. His lectures on Western culture and philosophy aimed to preserve a thirst for knowledge and spirituality, instill pride and nobility, and inspire his listeners to overcome their impossible circumstances.

Baeck feared for prisoners’ humanity even more than for their physical well-being. Hence his controversial suppression of information he received in August 1943 about the systematic massacre of European Jewry, lest his fellow inmates give up the struggle to survive.

Baeck’s humanist philosophy also explains his efforts to spare the German guards when the Russians left them at the mercy of the camp prisoners. In the name of justice, law and order, and humanity, he discouraged the natural desire for revenge, exhorting survivors to look beyond their suffering to the new world they had yet to build. He dreamed that they would step, whole in spirit, into a new, more humane reality in which their rich, spiritual heritage could make the world a better place.

Left Only with God

Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira (1889–1943), the Piaseczno Rebbe, was one of the greatest Hasidic leaders in Poland between the two world wars. Like Rabbi Ziemba, Rabbi Shapira spent the Holocaust years in Warsaw, but he remained in the Warsaw ghetto until its liquidation and was most likely murdered in a labor camp near Lublin. The rebbe was known as a skillful educator and an eloquent philosopher well before the war that destroyed European Jewry, but he is best known for his masterpiece written in the throes of the Holocaust, Holy Fire (Esh Kodesh). Before the liquidation of the ghetto, he hid these sermons on the weekly Torah portion in a canister. They were found and published after the war. His pre-war volumes, especially Hovat Ha-talmidim (The Students’ Duty), illuminate his uncompromising educational method and the depth and rigor he demanded of his students, many of whom became outstanding leaders.

Rabbi Shapira lost three of his nearest and dearest before his nineteenth birthday: his father, Rabbi Elimelech Shapira of Grodzhisk, who died when his son was only three; his grandfather Rabbi Hayyim Shmuel of Chęciny, who had been a second father to him; and a third father figure, his father-in-law, Rabbi Yerachmiel Moshe Hopstein of Kozhnitz. This personal bereavement may have developed his capacity to fill the same void for his most prominent students. In his vast correspondence with them, he expressed as much concern for their physical needs as for their spiritual achievements. His efforts to find escape routes to Palestine for all his main disciples to the land of Israel were further proof of his devotion. He refused to exert himself to save himself, especially after his beloved wife passed away two years before the war.

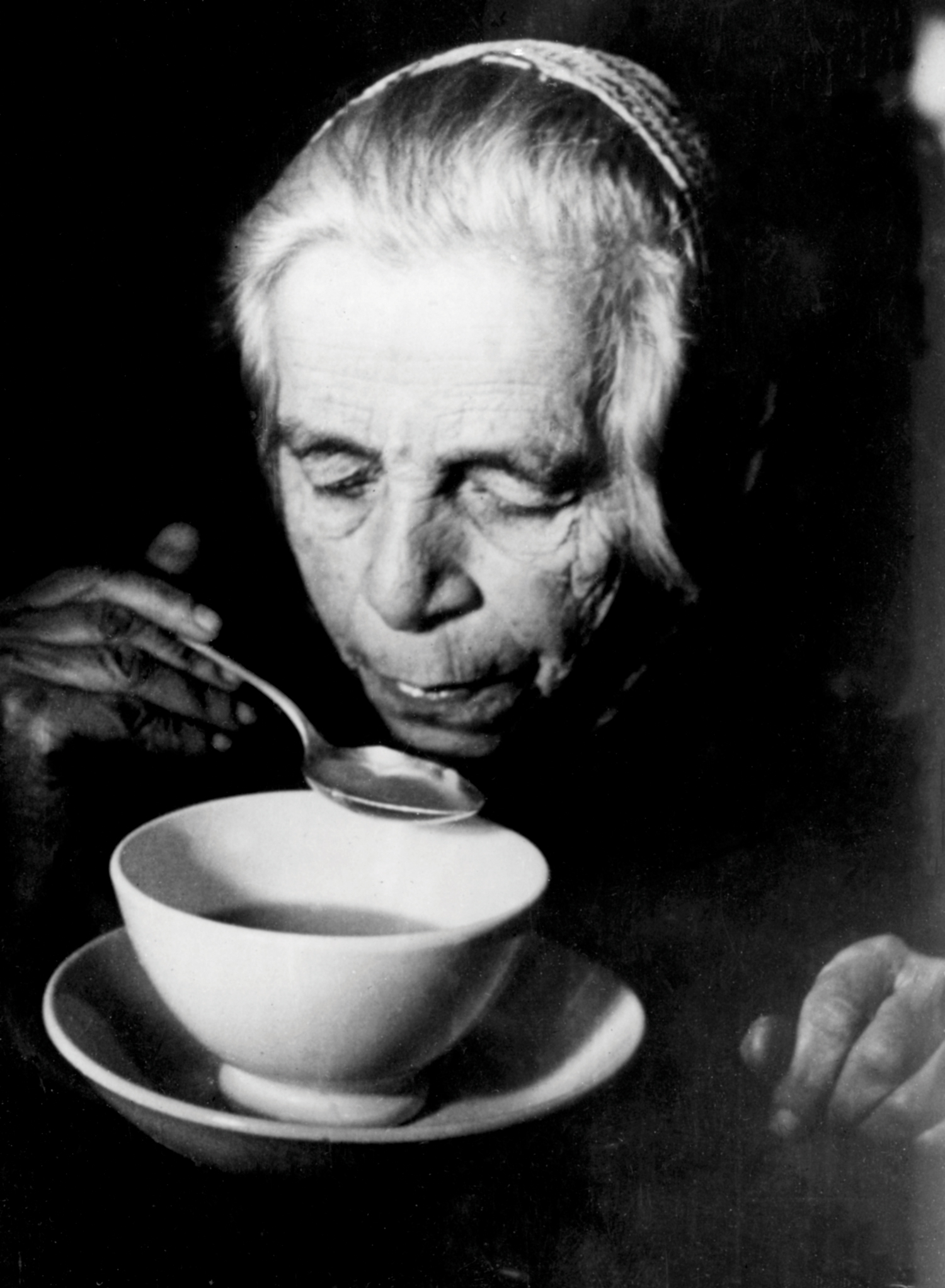

A spiritual giant. Before the Holocaust, the Piaseczno Rebbe strove to revive the revolutionary zeal of the first generations of Hasidism. His prescience saved many of the young men who flocked to learn from him. The rebbe before the war

The Rebbe lost his son, Elimelech Ben-Zion, his daughter-in-law, and her mother even before the Nazis reached Warsaw. His mother died shortly afterward. His spirit was completely broken when his daughter and her husband disappeared along with the thousands of Jews rounded up in the summer of 1942. Forlorn and destitute, he fell silent and never wrote again.

Nevertheless, the Piaseczno Rebbe lectured and wrote extensively until then. Throughout the Holocaust years, he adjured his followers not to lose faith nor abandon its practices. He urged that they cling to whatever vestiges of communal prayer, Sabbath observance, dietary laws and Torah study they could. He spoke of the value of every Jew, of each soul’s powerful connection with God despite the horrors of ghetto life.

Who Will Build the Future?

Eventually, the object of the rebbe’s exhortations shifted, and he began addressing God, holding him responsible not only for the physical catastrophe fast overtaking the Jewish people, but for the resultant spiritual one – the danger that faith, too, would be eliminated even if some remnant of the Jewish people survived. The study halls now emptied of Torah scholars posed the greatest threat, the Piaseczno Rebbe believed, for how could the Jewish nation rebuild without its spiritual heritage? How could survivors of a reality almost guaranteed to shatter faith and humanity hope to restore the moral values that were the Jewish people’s raison d’être?

In 1943, in the margin of his Holy Fire manuscript, alongside his 1941 discourse on the Torah portion of Ekev, the rabbi added a heartfelt cry:

There are no words with which to lament our sufferings; there is no one to admonish, there is no heart to rouse to religious activities. How difficult has prayer become! How difficult is Sabbath observance even for someone who truly wishes to observe it. So grieving about the future is out of question now; there is no spirit, no heart left for thinking about rebuilding destroyed institutions when the time comes that God will have mercy and deliver us. Only God can spare us and save us with the speed of an eyeblink, only He can rebuild what had been destroyed, only He can heal us, at the time of the great Redemption and Resurrection. Please, God, have mercy, and save us without delay. (The Holy Fire, pp. 113–4)

But even as he looked to God as the only hope, the Piaseczno Rebbe demanded that his flock do everything possible to keep its humanity, as well as its Judaism, alive.

Shades of Leadership

Although spiritual leadership obviously takes many forms, all these leaders had one common goal: to offer a spark of hope, of humanity, within the terrifying circumstances of the Holocaust. Each had his own “take” on communal responsibility and his own methods of coping with incomprehensible personal tragedy. Yet all four men bravely shouldered the burden of leadership thrust on them by their followers and did their utmost, within the limits of their own understanding, to alleviate others’ pain.