Fall of the Byzantines

In 1071, the Byzantine Empire was dealt a crippling blow when a tribe of Mongolians conquered Anatolia, today a popular tourist destination in Turkey. The Seljuks, as they were called, had left the Russian steppes to conquer Central Asia, converting to Islam along the way. With North Africa as well as the Iberian Peninsula firmly in Muslim hands, and the Seljuks now gnawing at its eastern border, Christian Europe was virtually surrounded.

Though Godfrey of Bouillon declined the title “king of Jerusalem,” he is shown here wearing the emblem of the kingdom – St. George’s Cross. The garland of fruits on his head (perhaps a veiled reference to Jesus’ crown of thorns) signifies humility. Detail from a fresco by Giacomo Jaquerio in Manta Castle, in Saluzzo, Italy

Byzantium, the eastern half of the Roman Empire, had been fading for a while. Its leader, former general Alexius I Comnenus, realized that without substantial allies, he couldn’t withstand the marauders for long. Ignoring the centuries-old feud that divided Byzantium from the western Holy Roman Empire, Alexius asked Pope Urban II to send in mercenaries as reinforcements. The pope agreed, hoping to unite all Christendom under his leadership.

In the winter of 1095, at the Church’s major council in Clermont, France, Urban ordered all clergy to urge the liberation of Jerusalem from the Muslim infidels. The pope’s call to violence, plunder, and adventure struck a chord (much as similar messages do among jihadists today), and soon every segment of the population was raring to go.

An ill-prepared rabble set out in the spring of 1096, little knowing even where Byzantium was, let alone the Holy Land. These Crusaders headed east through the Rhine Valley, seizing supplies and equipment mainly from defenseless Jewish communities, “the infidel in their midst,” and leaving a trail of murder, rape, pillage, and destruction. Twelve thousand Jews died in this first “People’s Crusade,” which continued along the Danube toward Jerusalem. But when Hungarian villages fought back, killing a few thousand Crusaders, the leaders fled homeward, and the rest dispersed with little to show for their trouble.

Later that summer, a “real army” of thirty-five thousand knights (including five thousand horsemen) set out, led by the flower of European nobility.

Alexius I couldn’t restore his Byzantine Empire to its heyday, but his canny political and military maneuvering – including summoning Christendom to his aid against the Seljuks and Muhammadans – stabilized it in a particularly turbulent period. Alexius, illustration from an 11th-century Greek manuscript in the Vatican Library

En Route to Jerusalem

For the past nine centuries, the Fatimids had been ruling the Holy Land from their capital in Egypt. At its height, the Fatimid caliphate had also included all of North Africa, Sicily, Yemen, and the Hijaz – the western half of the Arabian Peninsula.

Metz was just one of the major Jewish communities in the path of the murderous People’s Crusade. Auguste Migette, Massacre of the Jews of Metz in the First Crusade, oil on canvas, 19th century

While most Jews lived more or less peacefully in the large, powerful communities of Mesopotamia, Egypt, North Africa, Spain, and western Europe, a small number also held on stubbornly among the Muslim majority in the Holy Land. Well treated, they held key positions in the Fatimid administration, some even responsible for maintaining and defending the forts on the empire’s borders. Though Jews were scattered all over the Holy Land, the two largest centers were in Jerusalem and Ramle. These communities had their own customs and prayers, including extensive liturgical poetry and midrashic literature. The Christian minority was concentrated in its holy cities: Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Hebron, and in the villages around Mount Tabor in the Lower Galilee.

Peter the Hermit, a priest from Amiens, France, turned the masses against the Jews as the People’s Crusade advanced along the Rhine. Illustration showing Peter preaching to Crusaders, Illustrated London Reading Book, London, 1851

Arab historian Al-Muqaddasi wrote in the 10th century that Holy Land exports included olive oil, dried dates, raisins, carob, fabrics, soap, cheese, raw cotton, apples, pine nuts, mirrors, needles, carpets, and ropes. But this abundance ended with the Crusades.

Advancing steadily eastward, the thousands of knights conquered every major city in their path. The plan was to create a continuous swathe of territory along the coast, from Europe to the Holy Land. Yet this campaign often involved months of siege, sapping morale. Once they reached Antioch – then known as Antākiyyah, in southern Turkey – the Crusaders changed tactics and marched posthaste to Jerusalem. Thundering south, they bypassed fortified cities such as Tyre, Acre, Caesarea, and Arsuf and conquered Jaffa, making its port available to the Genoese ships that had accompanied them all the way from Europe. In a month, the knights were at the gates of Jerusalem.

On July 15, 1099, after just a week’s siege, the Crusaders breached the city walls and slaughtered thirty thousand Muslims and Jews. After almost five hundred years, Jerusalem was once again in Christian hands. Following prolonged deliberations, Godfrey of Bouillon was declared “Defender of the Holy Sepulcher” (unlike his successors, he’d refused the title “king of Jerusalem”).

Out of four hundred thousand men who’d left Europe, only forty thousand made it to Jerusalem, and only a few thousand were actually knights. But the tale of their triumph spread, bringing thousands more in their wake.

On Land and Sea

Though the First Crusade was conducted mostly by land, the Genoese fleet played a vital supporting role. Italy had three major maritime republics: Genoa, Venice, and Pisa. Generally, any republic whose fleet took part in a war received a portion of the spoils as well as the right to colonize and tax the conquered territories. Hence the Italian city-states’ entry into the crusading business.

Genoa’s contribution to the Crusade consisted of twelve ships and a thousand men, all instrumental in the capture of Antioch as well as Jerusalem. The archers proved deadly, and the masts were used to make siege towers. The booty Genoa received was immense, drawn from all the Crusader conquests.

Pisa sent 120 warships in time for the siege of Jaffa, shortly after the fall of Jerusalem. Although the Venetian fleet was ready to sail at more or less the same time, the city’s leaders preferred to wait and see how the campaign progressed before they risked alienating the Oriental markets from which they’d long been shipping Muslim and Byzantine exports to Christian Europe.

Three years into the Crusade, Venice dispatched a mighty fleet of two hundred ships, which were to remain at the Crusaders’ disposal from mid-June to mid-August 1100, in return for a third of all campaign spoils, the right to tax ships anchoring along the shore, and colonial powers. Plans to conquer Tripoli in northern Lebanon also granted the Venetians half the booty. Once all that was decided, Venice started building siege engines.

Acre or Haifa?

The Crusaders and their Venetian accomplices set their sights on Acre, then the main port under Muslim control. But Godfrey of Bouillon died before the offensive began, so the remaining Crusader leaders settled on a smaller port from which they could later attack their original target. Their choice was really just a citadel – a wall with watchtowers surrounding the houses built up against a large fort. Its name was Cayphas, but we know it as Haifa.

Unearthing Haifa’s Talmudic predecessor. Excavations in Tel Shikmona, 1992

There used to be only one place to drop anchor between Caesarea and Acre: in the western Haifa Bay. The town that developed there, mentioned by Second Temple Jewish historian Josephus and the Talmud, was called Shikmona, probably for its indigenous sycamores. One traveler dubbed it “the Jews’ Shikmona.” Peaking under the Byzantines, Shikmona was destroyed during the Muslim conquest. Meanwhile, Cayphas grew.

At first the town was sparsely populated, with a significant proportion of Jewish fishermen and dyers (tekhelet [azure] and purple dyes were produced from murex shells at various locations along the coast). Cayphas appears in the Mishna and Talmud as a center of learning, with scholars from Haifa named in texts from the Cairo Geniza. When the Seljuks conquered the Holy Land from the Fatimids in 1071, the Talmudic academy was moved from Jerusalem to Tyre, though the sages traveled south to Haifa to celebrate the Sukkot festival.

A fortress was built for Haifa’s governor and his garrison, mostly because of the town’s strategic value as a port. But compared to Acre, Haifa remained a minor player until shortly before the Crusaders arrived, when an upsurge in trade increased its importance. In 1055 a Persian traveler wrote that Haifa was woody, with date groves and seasoned shipbuilders. Its inhabitants apparently did well, for some were wealthy enough to donate to synagogues in far-off Egypt.

Shoulder to Shoulder

Everything we know about the Battle of Haifa in 1100 comes from two sources: Albert of Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle), a 13th-century chronicler whose secondhand reports of Crusader exploits include monks’ eyewitness accounts; and a Venetian monk who joined the First Crusade, naturally exaggerating its scope and virtues.

The Crusaders and the Venetian fleet approached Haifa in tandem, by land and sea, anticipating little resistance. Tancred de Hauteville, prince of the Galilee and head of an impressive group of knights, expected Haifa to be added to his principality, giving him sea access. Godfrey, however, was nervous about any local leader gaining the upper hand, and preferred to strengthen the central role of his own kingdom. On his deathbed, he awarded Haifa to outstanding knight Galdemar Carpenel – severely reducing Tancred’s incentive to fight.

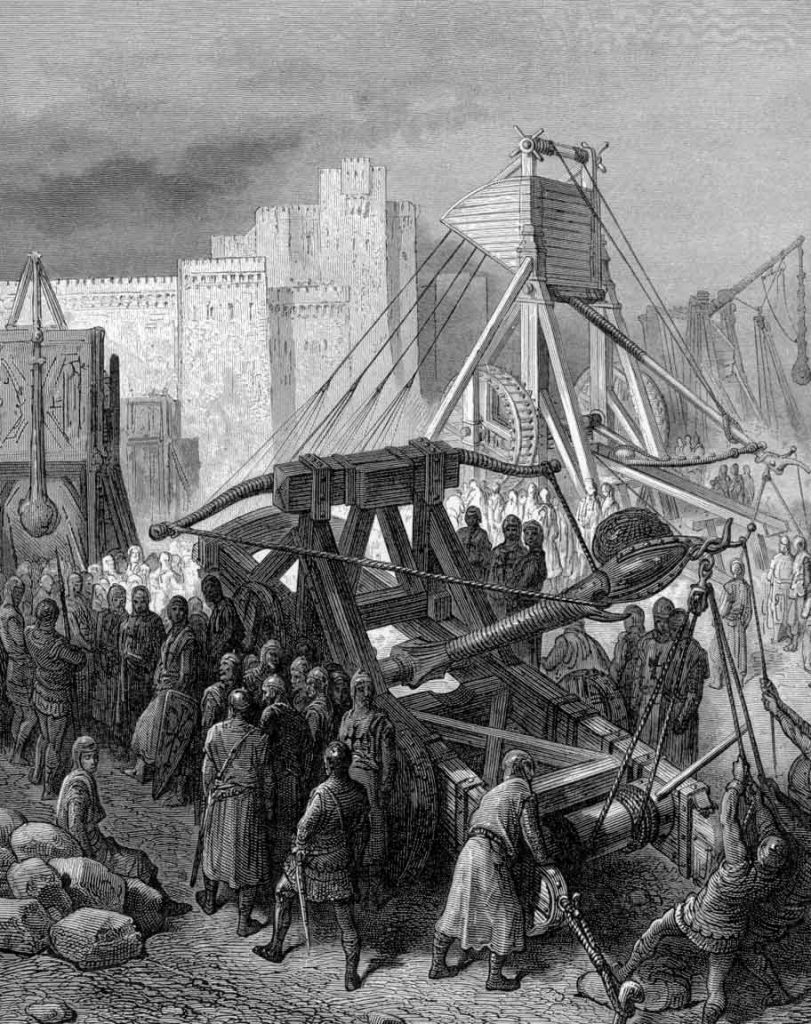

Crusaders use a catapult to bombard Jerusalem during the First Crusade. A similar device was used in the siege of Haifa. Etching by Gustave Doré, 19th century

The Crusader army offered the people of Haifa a truce – if they’d just convert to Christianity, they could retain not only their liberty but their property as well. Taxes would of course be paid to the new Christian rulers, but otherwise all would remain the same. But their Muslim and Jewish opponents withdrew behind their high walls, refusing to surrender their faith. They didn’t trust Crusader promises, especially given the rumored slaughter in Jerusalem. The defenders did try deterring their opponents by pointing out that Jesus and his followers had never set foot in Haifa, but to no avail.

Addressing his troops before battle, Bishop Enrico Contarini of Castello likened them to Maccabees – a comparison often used by Crusader leaders to lend their mission biblical proportions. Similarly, Albert of Aachen contrasts the Crusaders’ nobility with the vile blasphemy uttered by the boastful, foul-mouthed men of Haifa, “city of Satan.”

The two sides first faced off at sea, as the Venetian fleet confronted Muslim ships lying in wait. Great iron hooks were thrown onto the attacking vessels, sinking at least one. Unfazed, the Venetian sailors set fire to several Arab boats, putting the rest to flight.

On land, the Crusaders set up siege towers and a mangonel – a huge catapult hurling several projectiles at once. After a number of strikes, the Christians prepared to storm the walls. To the Crusaders’ surprise, a group of defenders ventured out and fought like lions, forcing the attackers back. The locals then withdrew to their positions on the ramparts, continuing to inflict heavy losses.

Undermotivated and discouraged, Tancred left the battlefield with his forces. The remaining Venetians and Crusaders knew Galdemar couldn’t vanquish the stubborn defenders of Haifa on his own. Tancred’s desertion was the last straw, and the Venetians prepared to sail south.

Dagobert of Pisa, the new patriarch of Jerusalem and commander of the entire operation, managed to lure Tancred back by persuading him that with the Venetians gone, there would be far greater spoils for whoever won the day. Furthermore, Dagobert more or less promised the city to whoever contributed most to its capture. The patriarch needed a speedy victory so he could hurry triumphantly back to Jerusalem and fill the leadership vacuum left by Godfrey’s death. Little did Dagobert know that Godfrey’s brother Baldwin had already seized the throne of Jerusalem.

Tancred understood that the Crusaders couldn’t prevail without him. So as trumpets sounded, his foot soldiers and knights in heavy armor charged into battle against the Jews and Muslims ranged along the walls. The Crusaders tried moving the siege towers close enough to climb onto the walls, enter the fort, and open the doors from the inside. But its defenders dropped boulders, hot pitch, and boiling oil on their enemies and stabbed at them with long spears. Burning arrows set fire to the bushes around the fort, and the wooden siege towers and battering rams soon went up in flames as well.

Yet the Christian soldiers kept fighting, even when their shields were burnt to cinders or pierced with as many arrow holes as a sieve. Emboldened by Patriarch Dagobert’s blessings, they used the Venetian ships’ masts to make new siege towers topping the city walls. Tancred ordered his men to hunt down as many animals as possible in the nearby Carmel forest, skin them, and cover the towers with the fire-resistant hides. This time the troops managed to erect the towers right next to the walls, scale them, and penetrate the stronghold. Once inside, the fighters threw open the gates, and Crusader forces poured in.

Conflicting Tales

Though they’d held off the Crusaders for a month and damaged the Venetian fleet, the Jewish and Muslim defenders knew the battle was lost and their fate sealed. They tried to flee, but nearly all were caught and executed. The Crusaders had no mercy on civilians either, and soon not a soul remained in Haifa. The victors took everything of value from the fortress – gold and silver, jewelry, clothing, horses and mules, oil, wheat and barley – scooping it up as fast as possible to avoid sharing it with the returning Venetians. By the time the ships reached the shore, all the booty was gone, and the huge fleet was left with nothing.

That, at least, is Albert of Aachen’s version. The Venetian monk tells a slightly different story, in which his countrymen were so touched by the sight of the battle-weary Crusader army that they donated their cut of the spoils on the spot. Yet other Venetian sources reflect severe disappointment that the operation turned out to be a financial fiasco. In the end, the Venetians had to pretend that they too had joined the Crusade out of religious zeal, with no thought of earthly reward.

The Crusaders probably had no idea they were fighting a mixed population, since they couldn’t distinguish between Arabs and Jews. Given Haifa’s Jewish majority, however, most of its defenders were presumably Jews. They struggled to protect themselves, their families, and their livelihood from a major naval power and thousands of knights stirred up into a religious frenzy. Whereas in Europe, minority Jewish communities were burned alive in their synagogues, in the Holy Land Jews bravely fought to the end. The Battle of Haifa was probably the last time Jews took up arms in defense of their homeland until the Jewish Legion was formed toward the end of World War I.

Just as Dagobert had promised, Haifa went to Tancred, while Galdemar had to make do with the Hebron hills. A few months later, Tancred succeeded his captured uncle as ruler of Antioch. As the new “king of Jerusalem,” Baldwin meanwhile turned the Crusader kingdom into a going concern. Quick-thinking, aggressive, and decisive, he swiftly overtook Arsuf and Caesarea, where his soldiers butchered the local Muslims, burning them inside their mosques. The Muslim garrison in Acre, a threat to Tancred’s forces in Haifa, was conquered in 1104 with the help of Genoese, Pisan, and Venetian ships, which blockaded the port for twenty days. With their support, and Norwegian reinforcements arriving in Sidon in 1110, other cities along the coast soon fell as well.

By 1118, Baldwin’s kingdom extended from Eilat to Beirut. He’d built forts, developed trade, and defended his borders against Muslim attack for eighteen years, all the while encouraging a constant flow of visitors from Europe, many of whom stayed.

So Who Were the Bad Guys?

Here we get to perhaps the nastiest part of the story: all along the coast, the Crusaders systematically stamped out the Jewish and Muslim populations. Atrocities were widespread, but since there were no survivors, the few eyewitness accounts are those of the perpetrators, which are hardly reliable. A lament found in the Cairo Geniza tells us what happened in Haifa as well as Jerusalem, Hebron, Jaffa, Lod, Osafiya and Ono:

They slew the elderly and my soul wept, horror seized me at the destruction of Haifa/ Haifa, city of renown, my heart rends at your loss/ Honor has been exiled from Israel, and the elders of the court are no more. (Haifa and Its Environs, an issue of Ariel: A Journal of the Archaeology and Environment of Israel, p. 51 [Hebrew])

This fragment is the only Crusader-era description we have of the destruction of the Holy Land’s many Jewish communities, though other sources indicate that Jews were slaughtered all over the country, and that those who survived fled. Some made it to still-Muslim Ascalon (Ashkelon) or Tyre; some were seized, sent to Italy, and sold into slavery; and some reached the safety of Byzantine or Seljuk territory. Others, despairing, converted to Christianity. No Jews were left under Crusader rule, which extended to Tyre in 1124 and to Ascalon in 1153.

The Crusader kingdom had all the trappings of a European court, including its own currency. Crusader coins from Antioch, early 12th century, showing Tancred in chain mail and turban

The Cairo Geniza contains fragments originating in the land of Israel from the 10th and 11th centuries, but virtually none from the 12th. No manuscripts, no liturgical poems – only a few pitiful letters from people searching for relatives captured by Crusaders and probably sold as slaves.

The Crusaders built numerous forts in their Kingdom of Jerusalem, each for a different reason. Montfort, for example, was constructed on the banks of the Galilee’s Keziv stream when knights of the Teutonic Order clashed with Templar and Hospitaller rivals and consequently had to leave Acre, then the kingdom’s capital, for headquarters of their own. Montfort today

Day-to-day contact with the natives gradually tempered the Crusaders’ fervor, and after a few decades they realized they needed the country’s residents if they wanted to produce anything. Without farmers, smiths, potters, weavers, and dyers – most of them Jewish – the brave knights would be unfed and unclothed. Gradually, then, Jews returned to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The Knights’ Halls, or Citadel of Acre, originally served as the Knights Hospitaller compound. This last Crusader outpost in the Holy Land was incorporated into Acre’s Ottoman citadel and also housed the town’s infamous prison

In 1179, eighty years after the First Crusade, Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela recorded the numbers of Jews he met in Acre, Tyre, Caesarea, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Ascalon, Tiberias, and the village of Alma in the Galilee. All together, he counted thirteen hundred, showing how slowly these communities recovered from being wiped off the map overnight.

Saladin reconquered Haifa in 1187, making it his military headquarters. Just three years later, in the Third Crusade, Richard the Lionheart took the town back, only to discover that Saladin had destroyed its defenses, including its stores of food and equipment. Finding nothing to steal, Richard and his troops marched onward.

Under Saladin, Jews were welcomed back to the country, including Jerusalem. Haifa once again became home to Jews, Muslims, and Christians, though its port wouldn’t surpass Acre’s again until modern times. Soon the Crusaders were just a distant nightmare – until their image was revamped and romanticized by European imaginations. So next time you see gallant Crusaders striding across a movie screen, remember which side you’re on. One person’s hero is another’s villain – it depends who’s telling the story.