Too Short a Story

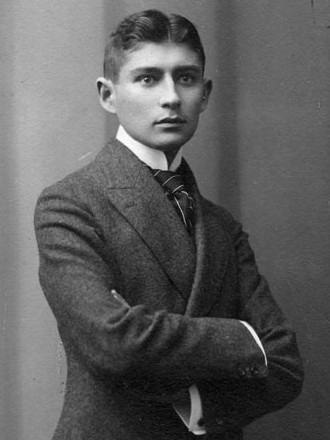

Franz Kafka was born in Prague in 1883 and died of tuberculosis at age forty-one. Although he published very little in his brief lifetime, Kafka became one of the most influential icons of 20th-century literature. British poet W. H. Auden even referred to “the Kafka century.” What was the secret of his unique literary style? How did he experience Judaism? And can he be considered a Jewish writer?

Linguistic Triangle

Kafka was born in one of the most important cities in the sprawling Hapsburg Empire, in which twelve different nationalities intermingled. Austro-Hungary labored to keep them all in check, peddling an uninspiring mix of German culture and Austrian patriotism. Yet nationalist fervor erupted in several hot spots, including Prague, capital of Bohemia. Like most of central Europe’s big cities, Prague was German in language and culture until the mid-19th century, when urbanization brought an influx of Czechs from the surrounding small towns and rural areas. By the beginning of the 20th century, this contingent was the majority, and about half of those listed as Germans in the Austro-Hungarian censuses were in fact Jews.

How best to tell the story of this diverse population? Until recently, scholars depicted Germans and Czechs as vying for ascendancy, squabbling over such matters as whether street names should be in German or Czech. Stuck in the middle, Jews were perceived as sitting on the fence, leading to increased anti-Semitism. Isolated, they took refuge in their own cultural expression, especially Zionism.

Today, however, the three ethnic groups are thought to have coexisted peaceably – even sociably – apart from arguments blown out of proportion by politicians and restless university students. Some of Prague’s most prominent Zionists – including their leader (and Kafka’s classmate), philosopher Samuel Hugo Bergmann – saw this integration as their key contribution to the Zionist cause. The cultural ease inbred by their native city would, they thought, allow them to bridge other gaps – between Jew and Arab as well as between eastern and western European Jewish culture.

Either way, Kafka’s unique style can’t be fully grasped without appreciating his complex political and cultural environment. In the original German, for example, Kafka’s coherence differs markedly from the unwieldy sentences employed by his German contemporaries. This clarity stems from his being an outsider to the German-speaking community, and from the linguistic sensitivity born of living in Prague’s ethnic jumble.

The Old City of Prague is one of Europe’s most popular tourist sites – and one of the most charming. In the 19th century, when it was built, its somewhat kitschy look was in vogue. View from the Old City toward the Charles Bridge, 1920

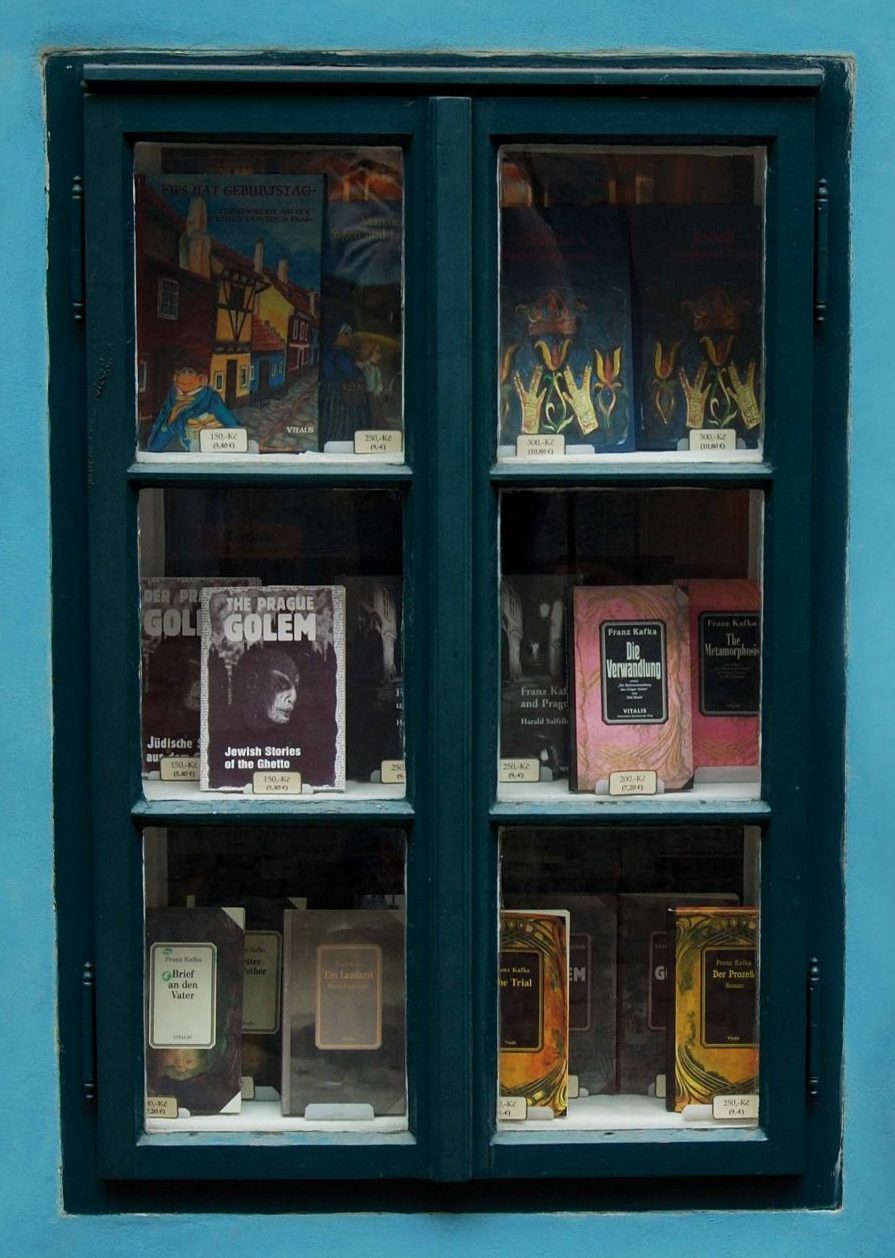

Today Kafka has become an emblem of Prague, commemorated throughout the city. Guides offer tours of “Kafka’s Prague,” in which this bronze statue by Jaroslav Rona – based on Kafka’s Description of a Struggle – is a highlight. Its location near Prague’s Spanish synagogue is also the area where Kafka lived most of his life

In His Father’s Shadow

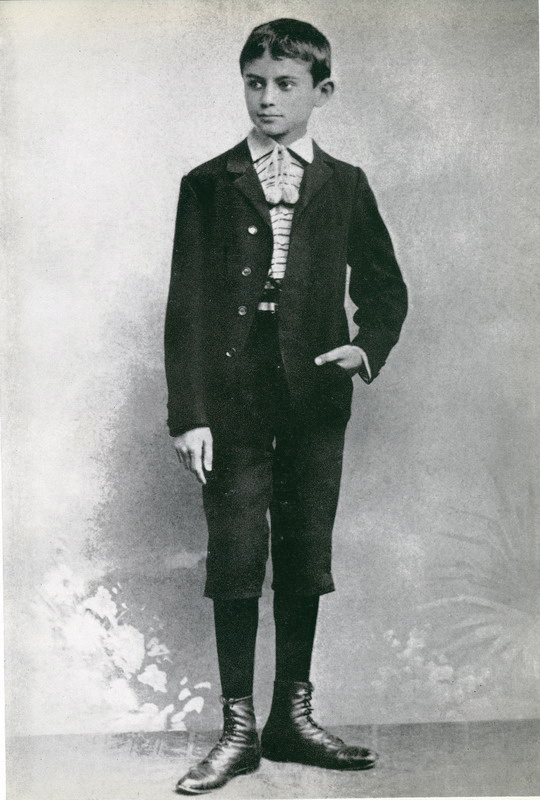

Franz Kafka was the eldest of six children born to Hermann Kafka and Julie Löwy. His two brothers died in infancy, and Franz grew up with his three sisters – Gabriele, Valerie, and Ottilie. Hermann Kafka was a successful fashion retailer, and he and his wife concentrated on their business while nannies and servants raised the children. Franz’s father was a self-made man, guaranteeing a life of affluence for his family. He expected his children – particularly his son – to follow in his hard-working, frugal footsteps, but to his great dismay, Franz refused. A yawning generation gap stretched between them, exacerbated by their different personalities. In 1919 Kafka wrote a hundred-page, unsent letter to his father, characterizing him as a crude, insensitive monster who tyrannized his family and employees. This caricature appears to be less a reflection of Hermann Kafka than a manifestation of the chasm between his bourgeois ideals and his son’s quest for self-fulfillment, freedom, and authenticity, inspired by the student-led revolutions of the late 19th century. The trauma inflicted on the young Kafka’s sensitive soul by such a strict and demanding father destroyed his personal life yet sowed the seeds of his phenomenal creativity, much of it devoted to painful family conflict.

For example, “The Metamorphosis,” written in 1912, is the perfectly crafted story of salesman Gregor Samsa, who wakes up one morning to find he has turned into an insect. Kafka’s convincing yet confusing portrayal of a part-insect, part-human consciousness is one of his greatest literary achievements. He traces how our devotion to career, convention, and family robs us of our authenticity and even our humanity. Even more shocking, the unfortunate Samsa is betrayed by his job, his society, and even his own family when he becomes a burden. Man’s only comfort – and redemption – lies in his art. Samsa ultimately suffers a slow and painful death because of an apple (symbol of Adam’s primordial sin) thrown at him by his own father.

“The Judgment” is another tale of tension between the individual and his family, society, and workplace, culminating in a similar tragedy: a father sentences his son to death by drowning, and the son obediently complies.

Fractured Heritage

Kafka’s education, like his home, was at once broad, cultured, and rigidly hierarchal; in a word, bourgeois. He was taught middle-class European values: etiquette, frugality, rationalism, and emotional restraint if not repression, with no room for passion or baser instincts. All these inform his work.

Kafka’s Jewish heritage was another matter. In Prague, and particularly in the Kafka home, there was little mention of Jewish tradition. Unlike most large central European cities, Prague had only a small Orthodox community with no rabbinical seminary. While Hermann Kafka identified strongly with his Jewish roots and firmly opposed his daughter Ottilie’s marriage to a Czech Christian, his objections had little to do with Jewish law. In his letter to his father, Franz bitterly bemoaned the feeble Jewish identity he’d inherited:

You really had brought some traces of Judaism with you from the ghettolike village community … the impressions and memories of your youth did just about suffice for some sort of Jewish life… . Basically the faith that ruled your life consisted in your believing in the unconditional rightness of the opinions of a certain class of Jewish society, and hence actually, since these opinions were part and parcel of your own nature, in believing in yourself. Even in this there was still Judaism enough, but it was too little to be handed on to the child; it all dribbled away while you were passing it on… . It was also impossible to make a child, over-acutely observant from sheer nervousness, understand that the few flimsy gestures you performed in the name of Judaism, and with an indifference in keeping with their flimsiness, could have any higher meaning. (Franz Kafka, Letter to My Father, p. 17)

His family’s break with tradition was a strong element in Kafka’s development, especially in his adult life, as he sought to enrich his knowledge of and familiarity with Judaism. He gave compelling expression to this particularly modern experience in “The Great Wall of China,” published after his death. The story’s narrator ponders the ancient Chinese emperors’ deeds, only to doubt whether these men ever actually existed:

Now, one of the most obscure of our institutions is that of the empire itself. … we think only about the Emperor. But not about the present one; or rather we would think about the present one if we knew who he was or knew anything definite about him. … but, strange as it may sound, it is almost impossible to discover anything, …from near or distant villages. … So vast is our land. (Franz Kafka, “The Great Wall of China,” in Kafka, The Complete Stories, pp. 274–5)

Nightmarish World

After graduating from the local German gymnasium, Kafka chose to study chemistry, but transferred to law school shortly afterward to accommodate his parents’ wishes. As was common, Kafka broadened his horizons with courses in art history and German literature. He also joined the Reading and Lecture Hall of the German Students, a liberal, mostly Jewish organization. While at university he befriended Hugo Bergmann, Max Brod, and Oskar Pollak. (Pollak later became an extremely promising art historian, though his life was cut short by World War I.)

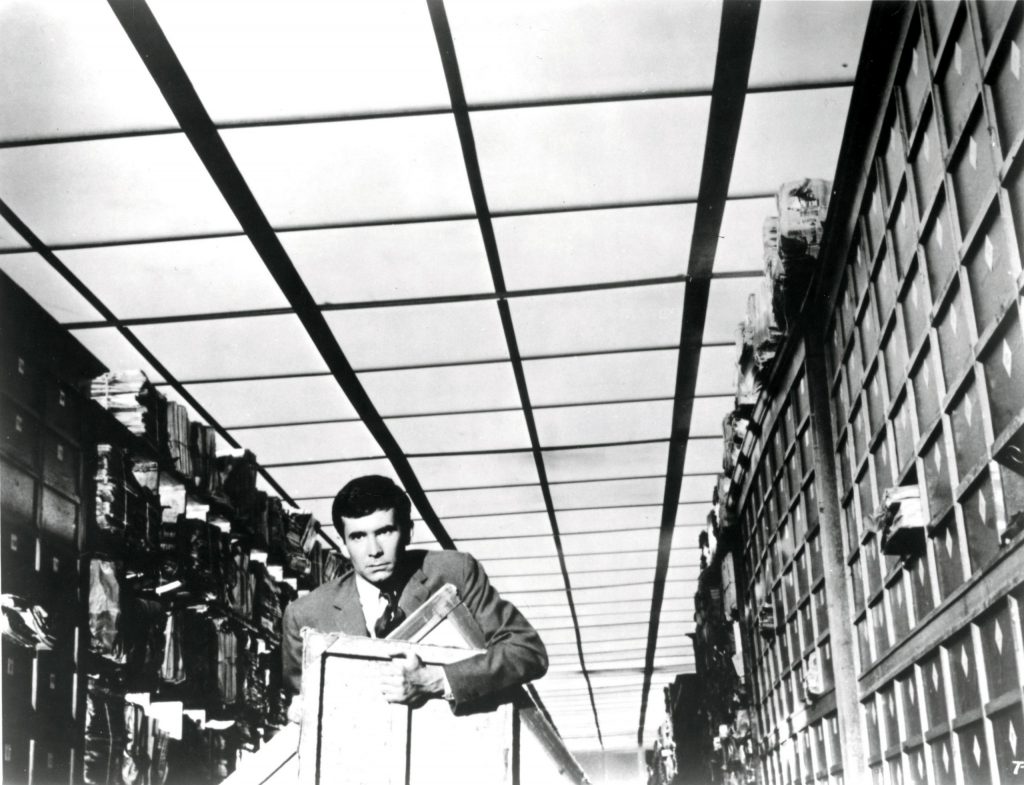

Kafka earned his Ph.D. in law in 1906. He was employed by the semi-governmental Workers’ Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia for over twenty years. Although Kafka’s writing suggests he was a small cog in a vast bureaucracy, he actually attained such a responsible position that he was hard-pressed to take sick leave when diagnosed with tuberculosis. Some of his darker, most Kafkaesque passages surely derive from the tragic accidents he dealt with daily.

Kafka was already dreaming of becoming a writer when he joined the company (he’d left his previous employer, an Italian insurance firm, because the long hours left him no time to write). Much of his early work has been lost, some of it destroyed by his own hand. One story he did publish, albeit partially, is a novella known today as Description of a Struggle.

Kafka never completed Description; in fact, he left behind far more unfinished works than finished ones. Like his confusing, even hesitant style, his fragmented output is just another illustration of his nightmare existence; an imperfect world with neither beginning nor end.

Writing as Revelation

Despite his apparent inability to complete anything publishable, Kafka viewed himself as an author. In one of his letters, he declared:

I have no literary interests; I am made of literature. I am nothing else and cannot be anything else. (Letters to Felice [New York: Schocken, 1988], p. 304)

From the day Kafka completed his academic studies until 1911, he devoted almost all his energies to writing. His utter, almost religious devotion to what he considered his true vocation may be the secret of the unique style that captured so precisely the maladies, pain, and hopes of the modern world. In his diaries and letters, he often described writing as a form of revelation, a complete nullification of the ego in order to embrace a higher inspiration.

In October 1911, Kafka finally emerged from his fairly isolated existence. Three years previously, at age thirty, he’d moved out on his own for the first time. Now he ventured out to watch a Yiddish theater group perform in a Prague café. The writer became obsessed with the troupe and forged close ties with its director, eastern European actor Jacques Levi. Over the next six months, Kafka attended all of the group’s performances and even organized a festive event in its honor, at which he gave a fascinating opening lecture on Yiddish language and culture.

Kafka was an obsessive theatergoer, and the Prague of his youth was a cultural center. The National Theater, Prague, 1890

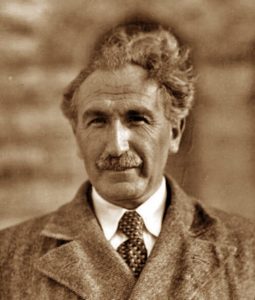

This talk was Kafka’s first serious attempt to embrace and deepen his Jewish identity. His aversion to the bourgeois western European Judaism of his parents and their generation made eastern Europe’s more authentic, easily identifiable Jews – despised and reviled as they were by their assimilated western counterparts – all the more attractive. Kafka’s close friend Max Brod also became interested in Jewish tradition, drawn in by the Yiddish theater and the Bar Kokhba Jewish student association, under whose auspices Martin Buber delivered his famous three addresses on Judaism between 1909 and 1911. Buber actually met with Kafka on a visit to Prague. At Brod’s urging, Kafka began delving into Zionism, though more as an expression of Jewish identity than as a means of establishing a Jewish state.

Max Brod, Kafka’s close friend and fervent Zionist, escaped from Czechoslovakia on the last train before the country’s annexation by Nazi Germany in 1939. Making his way to Palestine, he joined the Habima Theater but wrote and published in German until his death in 1968. Brod (right) with Habima members Baruch Chemerinski and Zvi Friedland, 1942

Kafka’s flirtation with Zionism led to romance. While staying with Brod in Berlin in 1912, he met young Felice Bauer, who also mixed in Zionist circles. Though literature was not Felice’s first love, and she was more down-to-earth than one might have thought would appeal to Kafka, the two forged a deep relationship, expressed in over five hundred letters he subsequently sent to Berlin, often daily. Kafka’s rich inner world emerges more clearly from these letters than do his feelings for Felice; his missives contain more than a few true literary gems.

The couple became engaged in the spring of 1914. Two weeks later, Kafka shocked his parents by breaking it off. He and Felice resumed their correspondence two years afterward, and met in the spa town of Marienbad, in the Czech Republic. They were engaged again in the summer of 1917, but the writer soon began coughing up blood and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In response, he ended the relationship once more, took a leave of absence from work, and joined his sister Ottilie in the countryside, where she was working in agriculture. Kafka’s inability to commit to Felice exemplifies the fundamental dichotomy of his existence. On the one hand, both family and Zionism were important to him; on the other, he lived and breathed literature, and lofty artistic ideals were almost all that mattered.

Kafka saw in Zionism a valiant attempt to give physical expression to spiritual goals. He took the movement seriously, investing time and energy in learning Hebrew. Just as he made vigorous efforts to marry and have a family, he considered turning his romance with Zionism into reality by immigrating to Palestine. Yet he felt he was simply not pure enough to live in the Holy Land. Likewise, he broke his engagement partly because he deemed emotion and intellect incompatible with physical passion. His stories depict sexuality as aggressive and vulgar, and art as life’s sole redeeming aspect. His tuberculosis was the logical fulfillment of his conviction that earthly life was destined to waste away into a higher existence, as does the hero of the title story in his last published collection, A Hunger Artist. (Ironically, Kafka himself actually starved to death, his throat too sore to swallow.)

The Castle, an unfinished novel penned during Kafka’s final years, can be understood (as Brod interpreted it in his heavily edited first edition) within the Zionist context. It describes K., a surveyor obviously representing Kafka, who finds himself unable to contact the inhabitants of a nearby castle he believes to have hired him. The plot describes his fight to expose the weaknesses of a faceless bureaucracy and obtain a permit to settle in the surrounding village, which is finally and ironically granted only after his death. The permit symbolizes man’s quest to find his place in the physical world, which – according to Brod – also hints at Zionist attempts to settle the land of Israel. For Kafka, though, these ambitions are but an impossible dream.

Kafka’s Theology

As Kafka renounced the physical world, his unique theology emerged. Its first significant expression was in the form of aphorisms written during his convalescence in Zürau. Perhaps more explicit theologically were his two great, incomplete novels, The Trial (written between 1912 and 1914) and The Castle (1922–4). Both are modern allegories, simple yet shocking. Well aware of what he was developing between the lines of his stories, Kafka wrote in his diary early in 1922:

All such writing is an assault upon the border … which might have developed quite easily into a new esoteric doctrine, a Kabbalah, if Zionism had not intervened. (Max Brod, ed., Franz Kafka: The Diaries 1910–1923, January 16, 1922, p. 399)

Kafka embodied secular modernism. Rather than eradicating or struggling against religion, he sought to translate it into an everyday, secular context. Max Brod famously quoted him as saying that “writing is a form of prayer” (Brod, Franz Kafka: Glauben und Lehre, p. 234). Kafka took the ideals of religious devotion and asceticism and applied them to art. Yet his hunger artist fails to break through the barriers of mundane reality; he’s doomed from the outset by the commercialization and shallowness of modern life.

For Kafka, then, modern attempts to debunk the sacred while sanctifying the mundane through art, nationalism, and humanism can never succeed. Instead, he proposes an inverted theology and mysticism: God is not absent, just infinitely far away. The author described the resulting unbridgeable chasm between the spiritual and the physical:

This world … cannot be followed by a Beyond, for the Beyond is eternal, hence it cannot be in temporal contact with this world [of the] here and now. (Franz Kafka, The Blue Octavo Notebooks [1917–19], December 11, 1917)

All that remains is man’s Sisyphean struggle to attain the unattainable. Kafka describes this endless quest through Joseph K.’s fight for justice in “The Judgment” and K.’s efforts to gain access to the authorities in The Castle. One of the most powerful and well-known articulations of Kafka’s pessimistic theology is the parable he incorporates into “The Judgment.” The villager arrives at the gates of justice and seeks entry, only to be turned away by a terrifying guard. The guard assures him that an infinite number of sentries have been stationed along the path to block his way. But just before the villager dies, the same guard informs him that this gateway was designed for him alone, and now it must be closed.

Kafka wrote that there is hope in this world, but for God, not for us. Yet there’s a bright side to this philosophy, like the light radiating from the barred gates of justice. The world may be cold, cruel, and random, and God may be unthinkably distant, but for those courageous enough to abandon all hope of external redemption, their pain and suffering will enable them to find godliness within themselves.

After his death, Kafka’s negative theology gained popularity among modern intellectuals, particularly in the wake of the Holocaust. After Auschwitz, these thinkers could perceive God only through His absence.

But Kafka’s novels are not just theological. Polished yet raw, they expose the nightmare of indiscriminate violence to which he was witness. The anonymous bureaucracy of the government insurance company of which he was a part; the carnage of World War I, though he experienced it only secondhand (in his diary, Kafka records a dream in which he thrusts an enemy soldier into a burning oven); the rivalry between Czechs and Germans in Prague, still unresolved despite the postwar establishment of the Czech Republic – all forced him to confront the dark side of modernity. Kafka glimpsed the seeds of cruelty and alienation in bureaucracy, the arbitrariness of totalitarian regimes, and the commercialization of social ties and culture. The evil he depicts is more banal than intentional, made possible by betrayal, much as in “The Metamorphosis.”

End or Beginning?

To what extent was Kafka a Jewish writer and intellectual? The question has provoked intense debate among literary critics, even affecting the translation of his work. On the one hand, he was profoundly interested in his Jewish identity, learned Hebrew, and valued the religious culture and folklore of eastern Europe. After his final parting from Felice Bauer, Kafka was romantically involved with Julie Wohryzek, a Jewish chambermaid with Zionist leanings. Some claim they were even engaged. In the last year of his life, he moved in with Dora Diamant, a Jewish woman from Berlin who came from an Orthodox family, and she was at his side at the sanitarium near Vienna when he died.

Kafka’s last love, Dora Diamant, was with him at the sanitarium when he died, and brought his body back to Prague for burial

On the other hand, Kafka felt detached from Judaism and engaged in an affair with his non-Jewish translator, Czech journalist Milena Jesenská, between 1920 and 1922. He told Milena that her opinion of Jews like himself was inflated, and that all deserved to be locked in a drawer until they suffocated. Some consider this pessimistic pronunciation an eerie premonition of Nazi atrocities just two decades later.

Though Kafka’s works are universal, his ability to describe the horrors of modernization is rooted in the special connection between Jews and modernity, as Yuri Slezkine notes in The Jewish Century (Princeton University Press, 2006). Education, mobility, urbanization, and the centrality of capital have characterized Jewish life since the Middle Ages. But these are also the characteristics of modernity, essentially priming Jews to play significant roles in the new era. No wonder Kafka’s literary works can be interpreted from Jewish as well as general perspectives.

Franz Kafka wanted all his manuscripts destroyed after his death. Thankfully, Max Brod ignored these instructions. Dora Diamant recalled how Kafka lit a fire one evening and burned every piece of his writing he still had. In Zürau several years beforehand, he’d written:

It is not inertia, ill will, awkwardness – even if there is something of all this in it, … that cause me to fail, or not even to get near failings: family life, friendship, marriage, profession, literature. … I have brought nothing with me of what life requires, so far as I know, but only the universal human weakness. With this … I have vigorously absorbed the negativity … of the age in which I live, an age that is, of course, very close to me, which I have no right ever to fight against, but, as it were, a right to represent. … I have not caught the hem of the Jewish prayer shawl – now flying away from us – as the Zionists have. I am an end – or a beginning. (Kafka, Notebooks, February 25, 1918)

From Kafka’s decision to destroy his manuscripts, it would seem that he’d chosen to become an end. Brod’s refusal to carry out his request transformed him, despite himself, into a beginning.