Pageant

September 4, 1946. Brimming with emotion, Ben Hecht stood center stage. Tears filled his eyes, blurring his view of the cheering crowds below. Of all his many plays, scripts, books, and articles, this time he’d given his all. Aside from his personal triumph, it was much larger than he, than any individual. Framed by the spotlight of Broadway’s legendary Alvin Theater, wearing the suit he reserved for premieres, Hecht knew this was a moment of national redemption that no one in attendance would ever forget.

Against the backdrop of the final act of A Flag Is Born, the cast took its bows, with Marlon Brando in the center. This was no ordinary performance; it was a fundraiser, perhaps the biggest ever on Broadway. Ben Hecht had engaged his considerable talents and connections to make this evening a smash. Running all over New York, cajoling, arguing, and even threatening anyone who stood in his way, he’d written, rewritten, and overseen the production’s every detail, ensuring unprecedented success.

Tevye’s Dream

The one-act play featured Tevye and Zelda, a pair of Holocaust refugees en route from the horrors of Europe to a new life in the land of Israel. Stranded in a ruined cemetery, they prepare to greet the Sabbath with prayer and song. They’re joined by David, an angry young survivor. First Zelda expires, then Tevye, and David decides to emigrate in their place and preserve their memory by defying the British Mandate and fighting for a Jewish homeland. Time and again, the action hinted at parallels to the U.S. War of Independence, also waged against Britain. In the drama’s final moments, David waved Tevye’s fallen prayer shawl and delivered an impassioned Zionist speech. The shawl became a flag, and the curtain fell.

Hecht recruited some of the biggest names in American culture and society for the event’s sponsoring committee, including composer Leonard Bernstein, novelist Lion Feuchtwanger, New York City mayor William O’Dwyer, and former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt; their responsibilities included both publicity and fundraising. One hundred and twenty Broadway performances plus a nationwide tour raised an unheard-of four hundred thousand dollars for Jewish immigration to Palestine.

In the run-up to opening night, the cast stayed at Hecht’s lavish suburban home in Nyack, New York. Famous Zionists enjoyed his hospitality as well. Around the pool, they rubbed shoulders with Irgun underground activists from Mandate Palestine, busily planning their next operation.

Brando, then just twenty-four, was already a rising star but eager to work with castmate Paul Muni, a well-known stage and screen actor. Later famed for his outspoken politics, Brando totally immersed himself in the project, speaking at fundraisers and working for scale.

Everyone involved in A Flag Is Born had rallied to Ben Hecht’s call, and many volunteered their services. Celia Adler, first lady of the Yiddish stage, played the heroine alongside Paul Muni and Marlon Brando. Muni (left), Adler, and Brando rehearse before opening night

Brando’s final speech as David was the play’s climax. Pointing a finger at his American audience, he demanded, “Where were you, Jews? Where were you when six million were burned to death in the ovens?” His voice rising, Brando repeated his question: “Where were you?!” The implicit accusation sent chills through his listeners, he recalled. Jewish girls wept in the aisles.

At the time there was a great deal of soul-searching within the Jewish community over whether they had done enough to stop the slaughter of their people; some argued that they should have applied pressure on President Roosevelt to bomb Auschwitz, for example – so the speech touched a sensitive nerve. (Marlon Brando with Robert Lindsey, Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me [Random House, 1994], p. 108)

Hecht cleverly exploited these emotions, ending each performance with an unabashed appeal: “Give us your money, and we will turn it into history” (David S. Wyman and Rafael Medoff, A Race Against Death: Peter Bergson, America, and the Holocaust [New York: New Press, 2002]). (One reporter complained that the play had cost him dearly, since aside from purchasing a ticket, he’d felt obliged to make a donation.)

Many critics raved, but the New Yorker panned A Flag Is Born as shallow propaganda. Denounced by British journalists as the most anti-British play ever staged in the United States, the show was banned all over the British Empire.

Chicago Sensation

Ben Hecht was born February 28, 1894, in New York, to Russian immigrants Joseph and Sarah Hecht. He grew up in Racine, a small town in Wisconsin, as part of a large, warm extended Jewish family featuring an assortment of loud uncles and crazy aunts. Hecht’s father was often away from home in connection with his work, so Ben spenta great deal of time with uncles in Chicago. After completing high school at sixteen, he moved to the Windy City himself, where he found occasional work as a crime reporter and photographer, supplying gory details for the Chicago Daily News.

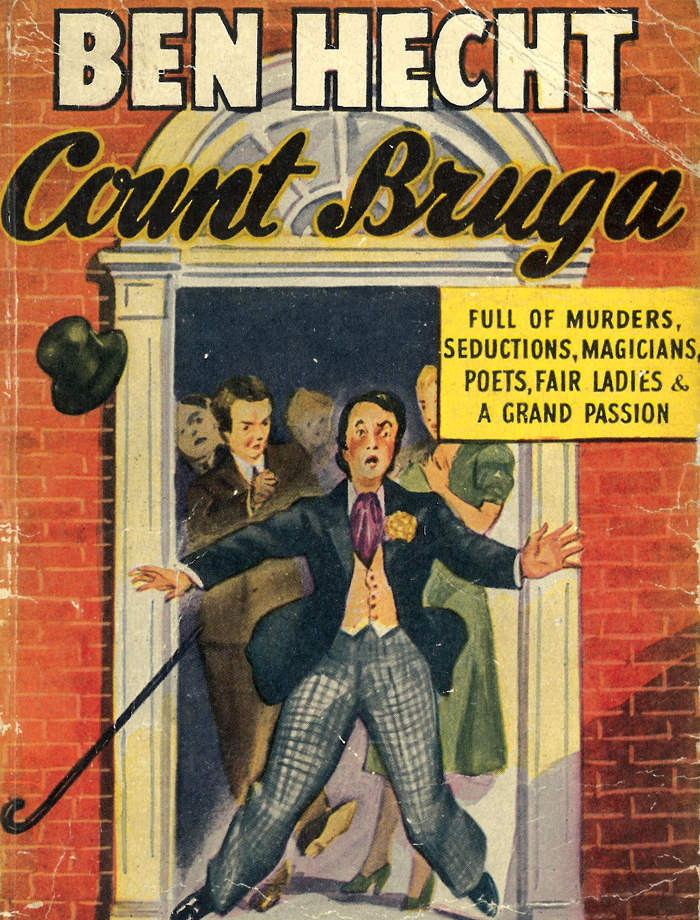

Hecht quickly developed a racy, sensationalist style, and his swift, sharp pen was a perfect match for the gang warfare, illicit gambling, drinking, and other vices plaguing Chicago. By 1920 he had his own column, and in 1921 his journalistic career peaked with an exposé leading directly to the conviction and execution of war veteran Carl Wanderer, the killer in a mysterious murder case. Fantazius Mallare: A Mysterious Oath, a novel Hecht published in 1922, was banned for its obscenity, propelling him to further celebrity.

An outstanding talent harnessed to the Zionist cause. Hecht in a publicity shoot for one of his films, 1949

In the late 1920s, Hecht moved to New York and branched out into theater with The Front Page, a comedy attacking journalistic and political corruption. Co-written with fellow Chicago reporter Charles MacArthur, the play won a Pulitzer Prize, ran for hundreds of performances, and became a successful film in 1931 (and again in 1974). Hecht received a much-quoted telegram from a friend, screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, cynically suggesting that he move to Hollywood: “Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.”

Scriptwriter Charles MacArthur, Hecht’s friend and co-writer at the beginning of his cinema career

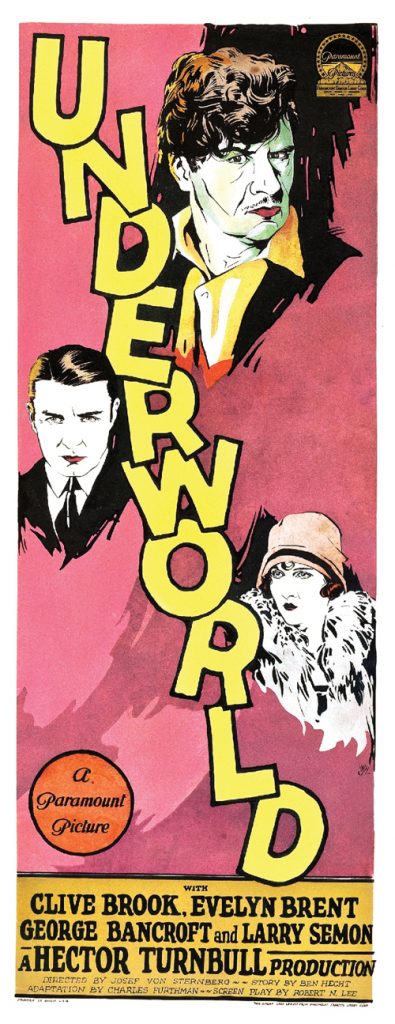

Always in need of money, Hecht headed west, where he wrote a series of box-office hits. Underworld (1927) earned him the first-ever Oscar for best screenplay. The classic gangster movie Scarface, based on the life of Al Capone, followed in 1932. Produced by Howard Hawks, it starred Paul Muni, and according to legend, two thugs paid a surprise visit to Hecht’s home after the “Boss” heard he’d been maligned on the silver screen. A panicked Hecht hastily assured Capone’s heavies that the film was only loosely based on him and certainly not intended as a biography. Mollified, they left him unharmed.

Hecht collaborated with MacArthur again in 1934, this time on a comedy, The Twentieth Century. By now, Hecht had a reputation for fast-paced, witty story lines, intimate knowledge of the underworld, and an ear for dialogue. Best of all, he wrote at a clip – Scarface took him just nine days.

Scarface, for which Hecht won an Oscar in 1932, was inspired by the Chicago gangsters he’d covered as a cub reporter. Movie poster

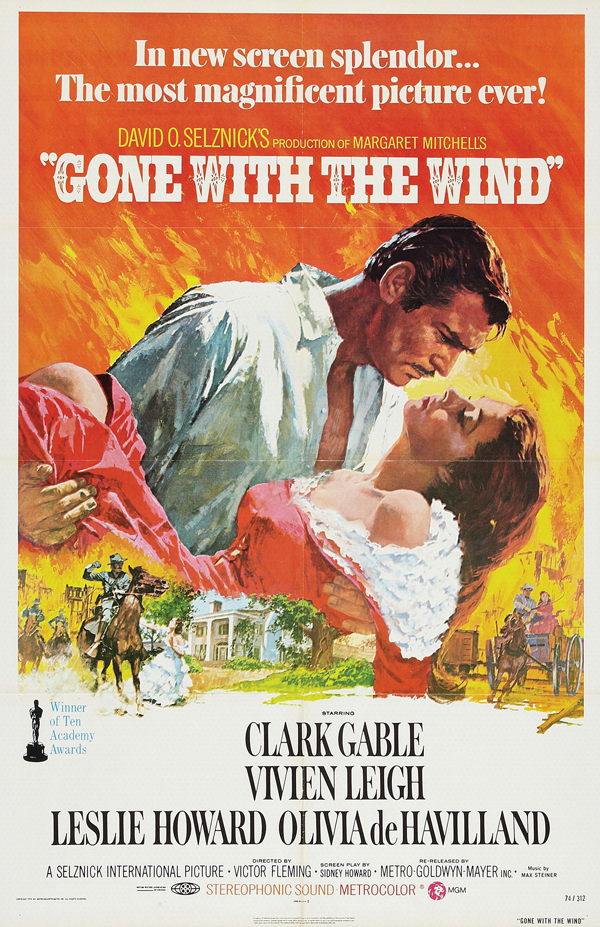

Hollywood began relying on Hecht as a “script doctor,” capable of turning floundering productions into blockbusters. Called to the set of Gone with the Wind after rewrites and replacement directors had made the film’s producers despair of ever cutting it down to size, Hecht had the script ready in five days. Yet the Oscar went to the original screenwriter, Sidney Howard.

Further successes – also uncredited – were Mutiny on the Bounty, The Shop around the Corner, and The Sun Also Rises, as well as the first James Bond film. He worked with Alfred Hitchcock as well, penning the scripts for Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946). All together, Hecht wrote twenty-five books, some twenty plays, over sixty-five screenplays, and hundreds of articles, columns, and short stories. But none of them created anything like the stir caused by his Jewish work.

A Jew Is Born

Having never paid attention to his Jewish origins, Hecht married Mary Armstrong, a non-Jewish Chicago journalist, in a civil ceremony in 1915. They divorced in 1925, after which the author wed Rose Caylor, also a writer, but a Jewish one. The first time he addressed Judaism was in his best seller A Jew in Love (1931). This extremely unflattering portrait of American Jewry earned him the dubious privilege of being banned from Jewish burial in Cleveland.

Hitler’s rise to power changed all that. In Hecht’s autobiography, published in 1954, he recalled:

My meeting with [Zionist activist] Peter Bergson was the result of my having turned into a Jew in 1939. I had before then been only related to Jews. In that year I became a Jew and looked on the world with Jewish eyes. The German mass murder of the Jews, recently begun, had brought my Jewishness to the surface. (A Child of the Century [Simon & Schuster], p. 517)

Joining the Fight for Freedom Committee to oppose isolationism and promote American military involvement in the struggle against Hitler, Hecht began focusing on German anti-Semitism in his column in the New York afternoon paper PM. In a piece titled “The Name of My Tribe Is Israel,” he added:

I write of Jews today, I who never knew himself as one before, because that part of me which is Jewish is under a violent and apelike attack. My way of defending myself is to answer as a Jew […].

My angry critics all write that they are proud of being Americans and of wearing carnations, and that they are sick to death of such efforts as mine to Judaize them and increase generally the Jew-consciousness of the world. […] I don’t advise you to take off your carnations. I only suggest that you don’t hide behind them too much. They conceal very little. (ibid., p. 521)

Hecht also helped stage a rally for the committee, which included various celebrity acts and a one-act play he wrote with MacArthur, Fun to Be Free. Seventeen thousand people turned out on October 5, 1941.

The Bergson Group

When Hecht met him, the mysterious Peter Bergson was visiting the United States from Jerusalem. His real name was Hillel Kook, but as his mission for the Revisionist Zionist Irgun militia was a secret, he kept his connection with his uncle – Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, chief rabbi of Mandate Palestine – under wraps. An Irgun officer since 1937, Bergson contacted Hecht after reading “My Tribe” and invited him to join his “Bergson Group,” which was producing and distributing anti-Nazi materials in the hope of mobilizing the U.S. to save the Jews of Europe.

Ben Hecht became a member of the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews, though he thought its aim quite insane: to persuade the Allies, headed by America, to arm a Jewish fighting unit – made up of residents of Palestine and refugees from Europe – to battle the Nazis.

Hecht brought considerable assets to the campaign. While Jewish causes had traditionally kept a low profile to avoid anti-Semitic backlash, he took out full-page advertisements in leading dailies. Pulling every string he could on Broadway and in Hollywood, Hecht recruited his famous friends in the entertainment industry. Celebrity support coupled with highly visible posters did the trick, making the Jewish army the most talked-about issue among American Jews in 1941–2. The public pressure exerted by the Bergson Group reinforced behind-the-scenes efforts by politically prominent Jews, and the British government announced the formation of the Jewish Brigade.

As rumors of Nazi mass killings and other atrocities gained credence, the Bergson Group turned to publicizing these facts and convincing the United States government to help Jewish refugees. Now the group’s ads screamed bloody murder, in stark contrast to the measured tones of editorials trying to divert attention from Allied inaction on behalf of victims of Nazi terror. Media opinion shifted, and the message began echoing loud and clear in the corridors of Congress, even reaching the White House.

One of Hecht’s advertisements, titled “My Uncle Abraham Reports,” described the ghost of his uncle – killed by the Nazis – sitting on a White House window sill a meter or so from President Roosevelt and waiting in vain for the United States to save the remainder of his family and nation. The president’s inner circle reported that he was infuriated by the depiction.

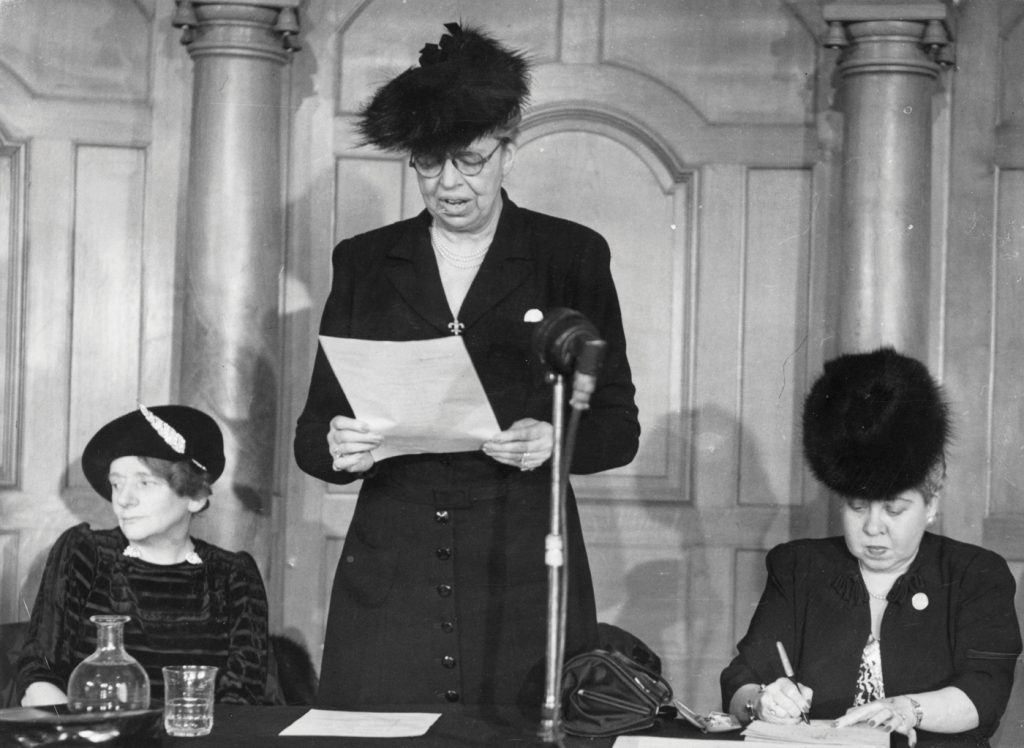

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt is famous for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights she formulated as chairman of the United Nations Human Rights Commission after the Second World War. Her appearances at Hecht’s Zionist productions were part of her personal, humanitarian struggle for war refugees. Roosevelt speaking in 1940

The text of another ad was leaked to Joseph Proskauer, head of the American Jewish Committee, who summoned Bergson to his office and warned him that such incitement could lead to pogroms on American soil. Bergson agreed to delay publication, on condition that Proskauer send lobbyists to prod the U.S. government into action. When the Roosevelt administration remained unmoved, Hecht responded with “The Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe.” “O World, be patient,“ it warned, “it will take / Some time before the murder crews / Are done. By Christmas you can make / Your Peace on Earth without the Jews” (New York Times, September 14, 1943).

There were no pogroms.

“We Will Never Die”

Toward the end of 1942, Hecht envisioned a pageant to publicize Hitler’s crimes. Dubbed We Will Never Die, the spectacle was staged against a background of the Ten Commandments – in the shape of two enormous, fifteen-meter-high “stone” tablets – and contrasted the Jewish contributions to humanity with the Nazis’ wanton destruction of Jews and Judaism. The climax was the Kaddish prayer for the dead, read by elderly rabbis rescued from the war.

Rehearsal for the Hollywood Bowl performance of We Will Never Die, July l943, with music composed and conducted by film composer Franz Waxmann

We Will Never Die premiered in New York’s Madison Square Garden on March 9, 1943. Starring Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, the show was performed there twice and seen by over forty thousand people. It then toured six major U.S. cities. In Washington, the audience included First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, six Supreme Court judges, and three hundred Congressmen. Receiving extensive media coverage, the pageant broke the “conspiracy of silence” (as another Bergson ad called it) surrounding the genocide in Europe – and marked the birth of an American protest movement to fight it.

The Bergson Group’s campaign peaked in September 1943, when Congress debated the creation of a government agency to rescue Jewish refugees. Roosevelt set up the War Refugee Board in January 1944, which brought more than two hundred thousand homeless men, women, and children from Europe in the last fifteen months of World War II.

In the war’s final months, the Bergson Group drummed up American support for illegal Jewish immigration to the land of Israel and for the Jewish militias fighting the British there, especially the Irgun.

Once again, Ben Hecht’s gifts placed a fringe political movement center stage, as his A Flag Is Born exposed the cruelty of British rule and urged the establishment of a Jewish state. And once again his connections worked their magic, with such prominent entertainers as Harpo Marx, Frank Sinatra, and Leonard Bernstein endorsing the Zionist ideal.

Renamed the American League for a Free Palestine, Bergson’s organization kept its agenda in the public eye with vitriolic full-page ads against the British administration in Mandate Palestine.

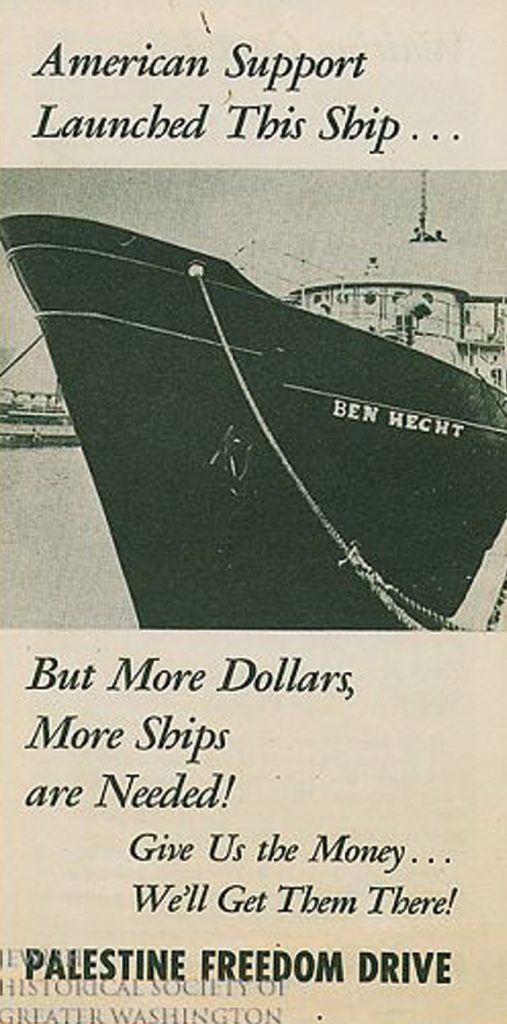

All funds raised by A Flag Is Born went to save Holocaust refugees. The Irgun purchased a derelict yacht it renamed the Ben Hecht – the only illegal immigrant ship honoring a living person. On December 26, 1946, the vessel sailed from America to France, docking under a Honduran flag at Porte-de-Bouc. The twenty-man crew worked with Hagana agents to bring hundreds of displaced persons aboard.

Six hundred had converged on Porte-de-Bouc from all over Europe. After a short ceremony, featuring the anthem of the Beitar Revisionist Zionist movement as well as Ha-tikva, the would-be immigrants boarded the ship at midnight. They set sail on March 1, 1947, only to be sighted by British patrol aircraft a week later. Navy destroyers followed the boat and demanded its surrender, but the crew ignored the loudspeakers, determined to reach shore under cover of darkness. At 4:30 pm, the ship ran into a naval blockade, and a hundred sailors armed with rifles, truncheons, and tear gas stormed the deck. The seamen met no active resistance, and the Ben Hecht was towed into Haifa.

The refugees were deported to Cyprus, but the crew members were arrested and thrown into the infamous Acre Prison. U.S. diplomatic intervention assured the Americans among them safe passage home, where they received a hero’s welcome in New York. The mayor hosted a reception for them, and Ben Hecht organized a dinner in their honor. He also announced that a new play of his would cover the costs of purchasing and outfitting a new ship to replace the one he’d lost.

Britannia vs. Hecht

The ads Hecht wrote after World War II were particularly incendiary, urging violence against the British authorities in Mandate Palestine. One solicited donations to the Jewish “Underground Railroad,” drawing a parallel between the struggle for freedom from slavery and the Zionist struggle against the British. Another warned that “the explosion of grenades and mines in Jerusalem this week are [sic] but a prelude to what is ahead,” unless the Mandate government withdrew immediately.

Most controversial was Hecht’s “Letter to the Terrorists of Palestine,” published a few days after Irgun activist Dov Gruner was executed in Acre Prison along with three of his colleagues. For the author, these men were no terrorists, and he lauded them as heroes comparable to George Washington. The letter also vowed that American support for the Jewish fighters would only grow.

The text was quoted on the front page of the New York Times, and the British government lodged an official complaint with U.S. president Harry Truman, claiming that Hecht was inciting the murder of British soldiers and officials. London further demanded that the Bergson Group’s tax exemption be revoked, but Washington found no grounds for compliance.

Though the group escaped punishment, Hecht paid a heavy price. In October 1948, well after the British withdrawal from Palestine and the establishment of the State of Israel, Britain declared a boycott of his movies, and his name was deleted from the credits of three films already playing in British cinemas. Hecht later took pride in the snub:

I felt perked up when word of the boycott first came out of England. I beamed on it as the best press notice I had ever received – a solid acknowledgment of the work I had been doing with all my might. […] An empire hitting at a single man and passing sanctions against him! There was something to swell a writer’s bosom and add a notch to his hat size. I could recall in history no other case of a nation’s declaring war on a lone individual. I was impressed. (Stella Paul, “Meet Ben Hecht, Wisecracking Jewish Hero,” American Thinker, Feb. 20, 2013)

But the boycott affected Hecht’s career at home as well as abroad. He was no longer warmly welcomed in Hollywood, and directors who’d made millions on his scripts now refused to hire him for fear of endangering their English markets. A few filmmakers did take him on, for half his standard fee, and on condition that his name be omitted from the credits. Hecht agreed without complaint. Having stood on principle, he was prepared to accept the consequences. His conscience was clear – he’d answered his people’s call.

Perfidy

After the seizure of the SS Ben Hecht, the Bergson Group continued bringing immigrants to the land of Israel and smuggling arms to the Irgun. Chief among these operations was that of the Altalena. This Irgun ship carrying immigrants and ammunition was sunk off the coast of Tel Aviv on Ben-Gurion’s orders in June 1948. (The Irgun was being absorbed into the newly established Israeli army, so Ben-Gurion refused its demands that much of the weaponry onboard be reserved for its fighters.) The Altalena’s voyage was paid for partly with funds raised by Ben Hecht.

In an act of profound identification and empathy, the Bergson Group had dissolved on May 5, the date of the establishment of the State of Israel. The organization gifted its assets to the state, including its office buildings in Washington, which subsequently served as the first Israeli Embassy in America. Yet Hillel Kook was among the Irgun officers arrested by Israel’s first government in the aftermath of the Altalena affair.

After the establishment of the state he’d worked so hard to found, Hecht was left with a sense of disappointment and anti-climax. Disillusioned by the actions of Ben-Gurion and Moshe Sharett – Israel’s first two prime ministers – against his Irgun friends, he was also put off by the socialism of the new country.

Much of Hecht’s biting criticism went into his book Perfidy, which describes the case of Rudolf Kastner, the Jewish Agency official who negotiated with Adolf Eichmann for the lives of select Hungarian Jews. Hecht’s work indicted the entire Jewish establishment in Mandate Palestine during World War II, accusing Zionist leaders of selling out Hungarian Jewry as a whole.

Hecht considered Perfidy his legacy to both the Jewish people and mankind. In answer to the question at the heart of the book – how could Labor Zionists have caused the deaths of so many Jews? – he wrote:

In the hearts of Israel something has been overthrown. An illusion has collapsed. The face of the government of Israel will no longer be the face of Hebrew dreams, but the scandal-pocked winner’s phiz of the politician. Not to all, but to many. (Hecht, Perfidy [Milah Press, 1997], p. 163)

Still Sailing

In the 1950s and ’60s, Hecht compered a TV show in New York and produced more books and scripts for both film and television. He went back to the glitz of Hollywood and Broadway, lived extravagantly, and died penniless at age seventy on April 18, 1964. His memorial service was held in the Reform Temple Rodeph Sholom in New York, attended by cinema’s leading lights as well as famous politicians – first and foremost, Menachem Begin, then head of Israel’s opposition party, Herut (Freedom), born out of the Irgun.

Yet the SS Ben Hecht lives on. Confiscated by the British Mandate authorities, the boat became part of Israel’s naval fleet under a new, Hebrew name: the INS (Israeli Naval Ship) Ma’oz (Stronghold). In 1955 it was sold to an Italian firm, which dubbed it the Santa Maria Del Mare and pressed it into service as a ferry in the Gulf of Naples. After another fifty years of extensive use, it was refurbished in 2009 as a private yacht and sold in 2010. It would seem to be the sole pre-state illegal immigration ship still sailing today.