Making and Baking

Eager to leave Pharaoh’s bondage, the Hebrew slaves freed from Egypt approximately 3,300 years ago baked the dough they had hastily kneaded before it had time to rise. That act gave the holiday of Passover its character – and its other biblical name: the Feast of Matzot.

Illustration by Uri Feibush from the Copenhagen Haggada, watercolor on parchment, 1739

Mix flour and water, bake it within eighteen minutes, and presto, you have matza, the unleavened bread eaten on Pesach. Matza is one of the few utterly Jewish icons left. Ever since the Exodus, Jews everywhere and of all stripes have baked or procured matza for Passover. So central was matza to the Jewish people that many medieval illuminated manuscripts contain hand-painted images of matza-making.

And not just any matza. It must be kosher for Passover.

Preparing matza. Illustrations from the Rothschild Miscellany, commissioned by Moshe ben Yekutiel Hakohen and dated to 1479, reflect the rich manuscript illumination of the Italian Renaissance

The matzot eaten at the Seder, the festive holiday reenactment of the Exodus, must be made of wheat, spelt, barley, oats, or rye. From the moment it’s harvested, this grain is guarded from moisture, lest it begin to leaven. Likewise, the flour made from this grain is protected from contact with water until the two are mixed to form dough. According to tradition, the water should be drawn from a spring (as opposed to tap water) and must not be warm, lest it speed up the leavening process. Therefore, the water is drawn the evening before baking and stored in a cool room.

Even when to bake the matza has been a concern. For much of Jewish history, matza was preferably baked on the afternoon before the Seder. This custom was so entrenched that the 11th-century Ma’aseh Ha-Geonim records the shocking story of someone who baked his matza in the morning instead, only to find that most rabbinic authorities prohibited its use at the Seder. Fortunately, two leading rabbis from Magence agreed that while one should avoid such scandalous practices, the matzas were permitted after the fact. The custom of baking on Passover eve is still observed by some today, often accompanied by joyous singing.

All Shapes and Sizes

For thousands of years, matza was made by hand. The flour was measured, the water drawn, and a timer was set for eighteen minutes. Then, amid excitement, song, and camaraderie, the dough was kneaded for the sake of the mitzva and rolled into circles. In some communities it was also perforated, so the steam would escape during baking (before the dough swelled into a pita). Finally, the dough was placed in a hot oven.

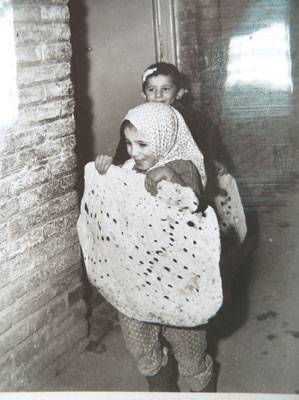

Each Jewish community made its matza slightly differently. Jews in Arab countries baked soft, thick, laffa-like matzot, slapping the dough onto the oven walls and peeling it off when brown. Iranian matzot were huge, close to a meter in diameter. The Iraqis marked the edges of theirs with one, two, or three “pinches” to show in which order they should be used during the Seder ceremony. The soft matzot of the Yemenites turned stale fast and were therefore baked fresh daily, whereas the thin, crackerlike Ashkenazic matza stayed crunchy all week.

The conversos, crypto-Jews of Spanish and Portuguese descent, developed means of keeping their matza incognito to avoid the long arm of the Inquisition. In Mexico, then still known as New Spain, these forced converts to Christianity found a unique local version of matza – the tortilla, a thin, unleavened flatbread made from finely ground maize or wheat flour. Despite several reports of Mexican matza baking, most conversos subsisted on this flatbread throughout Pesach. Coincidentally or not, the bread was traditionally eaten in Mexico during the Christian period of Lent (which coincides with Pesach) and is also known as pan de semitas, or Semitic bread.

Passover 1144 marked history’s first blood libel, in which the Jews of Norwich were accused of baking matza with Christian blood. Despite its absurdity, and despite Vatican denunciations, this charge has persisted, even appearing in upstate New York in 1928. It spread throughout the Muslim world in the 20th century, and surfaced as recently as 2007 in the Ukraine.

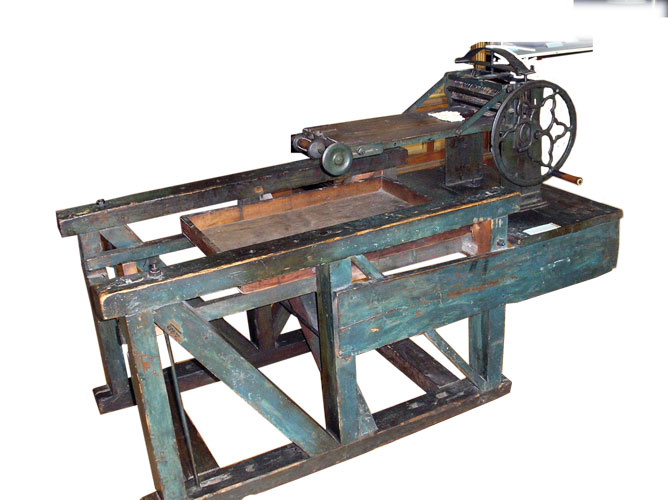

The Matza Machine

With the industrial revolution, hundreds of thousands of Jews migrated from the eastern European hinterland to the growing cities of Europe. Small, local bakeries could no longer meet the huge, short-term demand for matza in these population centers. The process was clearly a no-brainer for automation, and around 1850, a matza machine was invented. This contraption allowed much more dough to be mixed in one shot, and later versions mechanized the rolling and perforating as well. The rabbis debated the suitability of the new technology – at the end of each run, could the machine be thoroughly cleaned within eighteen minutes, before any dough remnants leavened, thereby compromising the kashrut of the next batch? But the wheels of progress were unstoppable: by the turn of the century, With the industrial revolution, hundreds of thousands of Jews migrated from the eastern European hinterland to the growing cities of Europe. Small, local bakeries could no longer meet the huge, short-term demand for matza in these population centers. The process was clearly a no-brainer for automation, and around 1850, a matza machine was invented. This contraption allowed much more dough to be mixed in one shot, and later versions mechanized the rolling and perforating as well. The rabbis debated the suitability of the new technology – at the end of each run, could the machine be thoroughly cleaned within eighteen minutes, before any dough remnants leavened, thereby compromising the kashrut of the next batch? But the wheels of progress were unstoppable: by the turn of the century, such huge American matza producers as Manischewitz, Horowitz Margareten, and Streit’s were baking hundreds of thousands of machine matzot, approved by all but the strictest rabbinic figures. Some authorities even deemed this matza preferable to the old-fashioned, handmade variety. Manischewitz actually patented the conveyor-belt oven used today in commercial bakeries.

Matza Everywhere

Without matza, many Jews would be close to starvation during the weeklong Pesach holiday. Thus, charitable matza distribution has long been a Jewish communal service, especially amid shortages caused by famine or war. The Joint Distribution Committee helped provide matza to thousands of displaced persons after World War I and II, and continues shipping it to places like Russia, Bulgaria, and Cuba.

Today many small Jewish communities import matza from centers such as Israel, the U.S., the U.K., and France. This was not always the case, however, though local matza production was sometimes laughable. In 1890, for instance, when the tiny New Zealand community was not yet fifty years old, it hired the non-kosher Aulsebrook Biscuit Company in Christchurch to bake matzas for Wellington and Auckland. When the local Jewish supervisor of the Aulsebrook matza production line left, the reliability of the matzot was called into question, and in 1892, cookie crumbs were indeed discovered in the matza!

In Israel, even zoos observe Pesach. According to Jewish law, Jews may not even own or derive benefit from leaven during the holiday. Since Israel’s zoos are Jewish-owned, all bread and crackers are therefore dropped from the animals’ menu. The gorillas at the Ramat Gan Safari expect a cream cheese sandwich every morning, but come Passover it’s cream cheese on matza. Their fellow primates get their share of matza too, as do most of the country’s ruminants. Elephants, however, don’t eat matza – their diet includes no grains.

Haggada Humor

Speaking of animals eating matza, one talmudic sage avers that fermenting dough – which must be speedily disposed of – may be fed to a dog (Jerusalem Talmud, Pesahim 3:5), possibly in gratitude to its Egyptian forebears: Exodus 11:7 recounts that no dog barked (or literally, “wagged its tongue”) on the night the Israelites left Egypt. This detail of the Exodus narrative inspired a whole genre of Haggada humor, with numerous Haggadot featuring slightly inane canine illustrations. The 15th-century German Yahuda Haggada, for instance, shows a tongueless dog entering a bakery, while in the 1478 Italian Washington Haggada (so called because it’s one of the treasures of the Library of Congress in Washington), a dog licks his chops as the Paschal lamb roasts.

Also (presumably) in a humorous vein, the 1526 Prague Haggada prescribes that before eating the bitter herb, “It is a universal custom to point to one’s wife, as the verse says, ‘I have found woman more bitter than death’ (Ecclesiastes 7:26)”!

To help make the Seder special, the Talmud forbids the eating of matza on Pesach eve. Rabbi Levi of the Jerusalem Talmud even states: “He who eats matza erev Pesach is like one who cohabits with his betrothed in his father-in-law’s house before the wedding” (Pesahim 10:1)! Yet leaven is also forbidden before the Seder. So what’s left to eat? Thus, the Second Nuremberg Haggada (c. 1540) depicts an agitated baker pointing at two boys hiding by the oven, snacking on matza. The rhyming caption reads, “They eat matza in hiding before the Seder,” and then quotes the Talmud’s startling comparison.

“I have found woman more bitter than death,” notes the book of Ecclesiastes. Illustration from the Washington Haggada, commissioned by Yekutiel ben Shimon from a workshop in Ferrara, Italy, in 1478. This image whimsically accompanies the passage in the Haggada explaining why bitter herbs are eaten at the Seder

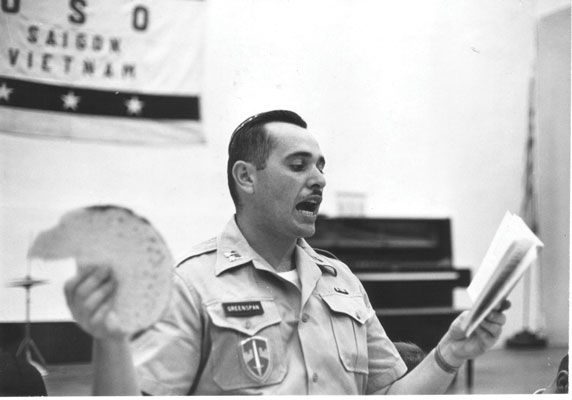

Marchin’ on Matza

Jewish soldiers have always struggled through Passover, and for centuries chaplains the world over have provided for their needs. One can find matza in most peacekeeping forces, from aircraft carriers to tanks, from Somalia to Afghanistan. The Israeli army in particular makes sure every soldier has access to matza, wine, and all other Seder necessities.

Sometimes Jews fought on different sides of a conflict, and both needed matza – as in the American Civil War. Joseph A. Joel of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment poignantly depicted a Seder held in 1862, the first Pesach of the war, in Fayette, West Virginia:

… being apprised of the approaching Feast of Passover, twenty of my comrades and coreligionists belonging to the regiment united in a request to our commanding officer for relief from duty, in order that we might keep the holy days, which he readily acceded to. The first point was gained, and as the paymaster had lately visited the regiment, he had left us plenty of greenbacks. Our next business was to find some suitable person to proceed to Cincinnati, Ohio, to buy us matzos. Our sutler, being a coreligionist and going home to that city, readily undertook to send them. We were anxiously awaiting to receive our matzos, and about the middle of the morning of Passover eve, a supply train arrived in camp, and to our delight seven barrels of matzos. On opening them, we were surprised and pleased to find that our thoughtful sutler had enclosed two Haggadas and prayer books. We were now able to keep the Seder nights, if we could only obtain the other requisites for that occasion.

We held a consultation and decided to send parties to forage in the country while a party stayed to build a log hut for the services. About the middle of the afternoon the foragers arrived, having been quite successful. We obtained two kegs of cider, a lamb, several chickens, and some eggs. Horseradish or parsley we could not obtain, but in lieu we found a weed whose bitterness, I apprehend, exceeded anything our forefathers “enjoyed.” We were still in a great quandary; we were like the man who drew the elephant in the lottery. We had the lamb, but did not know what part was to represent it at the table. But Yankee ingenuity prevailed, and it was decided to cook the whole and put it on the table; then we could dine off it and be sure we had the right part. The necessaries for the choroutzes [haroset] we could not obtain, so we got a brick, which, rather hard to digest, reminded us, by looking at it, for what purpose it was intended.

At dark we had all prepared and were ready to commence the service. There being no cantor present, I was selected to read the services, which I commenced by asking the blessing of the Almighty on the food before us, and to preserve our lives from danger. The ceremonies were passing off very nicely, until we arrived at the part where the bitter herb was to be taken. We all had a large portion of the herb ready to eat at the moment I said the blessing; each ate his portion, when horrors! what a scene ensued in our little congregation, it is impossible for my pen to describe. The herb was very bitter and very fiery, like cayenne pepper, and excited our thirst to such a degree that we forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups, and the consequence was we drank up all the cider. Those that drank the more freely became excited, and one thought he was Moses, another Aaron, and one had the audacity to call himself Pharaoh. The consequence was a skirmish, with nobody hurt, only Moses, Aaron and Pharaoh had to be carried to the camp, and there left in the arms of Morpheus. This slight incident did not take away our appetite, and after doing justice to our lamb, chickens, and eggs, we resumed the second portion of the service without anything occurring worthy of note.

There, in the wild woods of West Virginia, away from home and friends, we consecrated and offered up to the ever loving God of Israel our prayers and sacrifice. I doubt whether the spirits of our forefathers, had they been looking down on us, standing there with our arms by our side, ready for an attack, faithful to our God and our cause, would have imagined themselves amongst mortals, enacting this commemoration of the scene that transpired in Egypt. (J. A. Joel, “Civil War Seder Passover: A Reminiscence of the War,” The Jewish Messenger, March 1866)

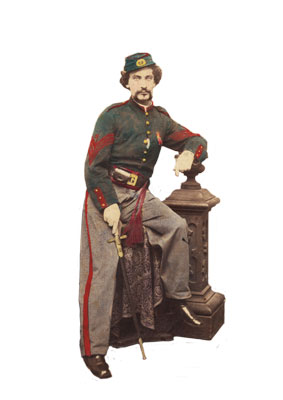

Hand-tinted albumen print of Joseph Joel in his Union uniform, a gift to his commander, Rutherford B. Hayes, after the Civil War

Other accounts describe how Isaac Levy of the Confederates’ 46th Virginia Infantry Unit inadvertently missed the first day of Pesach in 1864, but observed the holiday with a week’s worth of matza purchased in Charleston, South Carolina. Levy was killed in the Battle of Petersburg that summer. In another famous story, a Union soldier saw a boy eating matza in a captured Virginia town at the end of the war, and was invited to join his enemy’s Seder.

Matza remains a potent symbol of Jewish values, if not quite the world’s most delicious snack. On the one hand, it represents the dry, simple fare of the slave, reminding us of our humble origins. On the other, it heralds the freedom Jews long struggled to achieve. Small wonder that generations of Jews worldwide have gone to great lengths to get their hands on matza for Pesach.

Matza Against All Odds

Passover was particularly meaningful during World War II. The holiday’s themes of slavery and freedom reverberated in European Jews’ daily suffering – and matza was their most potent symbol. Jews even risked their lives to bake it. In both the Łódź and Warsaw ghettos, matza was produced as late as 1943. Although Jews in the concentration camps had great difficulty obtaining any food, many inmates scraped together wheat kernels for weeks, then baked matza in secret, late at night in the barracks. The Zarchiver Rebbe managed to bake it in Birkenau in 1943. One of his Hasidim, who had lost many teeth in a beating, was heartbroken that he couldn’t chew this precious matza. The rebbe told him to soak it, then eat it, despite the Hasidic ban on wet matza during Pesach.

I heard an even more unusual matza tale from Ralph Goldman, a ninety-year-old still working daily for the American Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC). In the 1980s, the AJDC delivered tens of thousands of food packages in the Soviet Union. Ralph brought one to the one-room apartment of a bedridden, poor old Jewish woman. An ace fighter for the Russian army during the war, she had downed many Nazi planes. She asked Ralph to take something out of her closet, where he found newspapers detailing her exploits. “That’s not what I wanted,” she said. “Take out the other thing.” Looking closely, he found a small, gray, rocklike item on the closet floor. As he put it on the table, she told him: “I couldn’t have survived in the army without eating bread on Passover. But I kept a piece of matza with me to put on the table, so I would remember it was Pesach. This is that matza; I’ve kept it for forty years.”