Prohibition

In 1919, the U.S. ratified a Constitutional amendment prohibiting the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcohol. The ban went into effect in 1920, and from then on it seemed that every American over age twelve had to have a drink. In one year, more than two hundred thousand unlicensed saloons, euphemistically called “speakeasies” and “blind pigs,” sprang up across the nation. The Prohibition era (1920–33) offered tough young hoodlums a chance to make big money. Consequently, large bootlegging organizations led by the lawless sons of Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants formed to quench America’s thirst – and rake in hundreds of millions of dollars.

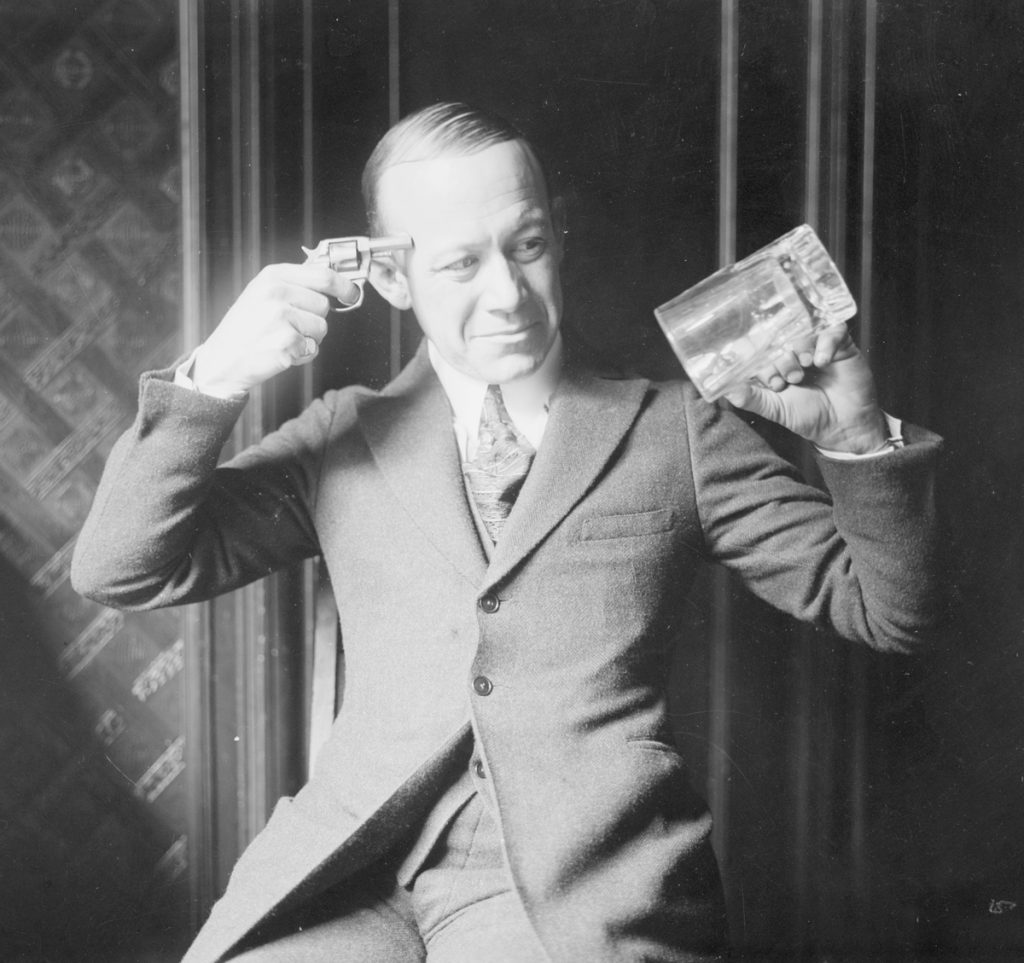

Bains News Service

Bains News ServiceLife was not worth living under Prohibition. Empty beer mug in hand, entertainer Ernest Hare threatens suicide on stage in 1920

Although Jews constituted less than four percent of the population, half of the major bootleggers were Jewish. Their business acumen, organizational ability, and ruthlessness allowed them to take advantage of the chaotic early days of Prohibition, when weak law enforcement provided endless opportunities for the unscrupulous.

New York City, then home to 1.6 million Jews, or forty-five percent of the nation’s Jewish population, spawned the greatest number of Jewish gangsters and crime bosses. The city also “supplied” them to other cities. Detroit’s notorious Purple Gang, for example, was led by the Bernstein brothers, transplanted New Yorkers.

The role of New York City’s Jews in organized crime has, not surprisingly, received less attention than the Jewish contribution to the arts, science, medicine, and journalism. Nevertheless, organized Jewish crime is an integral part of New York’s history, and to ignore it is to distort the Jewish experience of the city. Although several of New York’s Jewish gangsters achieved notoriety before World War I, Prohibition created undreamed-of opportunities for mobsters to gain national prominence and influence.

Photo by Al Aumuller, New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of Congress

Photo by Al Aumuller, New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of CongressLepke Buchalter, labor extortionist extraordinaire, in 1939

The Czar of the Underworld

The mastermind behind New York’s under-world was professional gambler Arnold Rothstein. Best known for allegedly rigging the 1919 baseball World Series, Rothstein pioneered organized crime in the United States. A man of remarkable energy, imagination, and intellect, he transformed petty larceny into big business. Rothstein was born into a wealthy Orthodox Jewish family but opted for an illegal path to fame and fortune. During the 1920s, he put together the largest gambling and bookmaking empire in the nation, launched a million-dollar stolen-bond business, and controlled most of New York’s gangs, narcotics traffic, bootlegging, and gambling, earning himself a reputation as “the Czar of the Underworld.” Writer Damon Runyon nicknamed him “the Brain” and used him as the model for Nathan Detroit, the main character in Guys and Dolls. F. Scott Fitzgerald also immortalized Rothstein, basing the gambler Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby on him.

Rothstein mixed with politicians and statesmen as well as bankers and bums. His payroll boasted a rogues’ gallery of famous New York gangsters, including Jack “Legs” Diamond, Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, and Frank Costello, as well as Jewish undesirables such as Meyer “the Little Man” Lansky, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, Dutch Schultz (born Arthur Flegenheimer), and Waxey Gordon. Rothstein’s life of crime, for which he never spent a day in jail, ended abruptly when he was shot dead during a card game in 1928. He was forty-six. The renowned Orthodox rabbi Leo Jung delivered the eulogy at his funeral, which was conducted – out of respect for the deceased’s father – in full accordance with Jewish law.

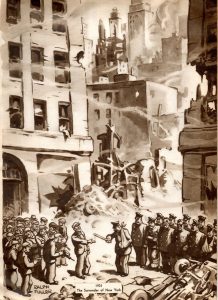

-

-New York cops surrender to the mobsters. Cartoon from Ballyhoo magazine, 1931

After Rothstein’s death, Gordon, Schultz, Siegel, and Lansky continued his bootlegging operations, while Buchalter concentrated on the extortion and protection racket. Rothstein famously taught his protégés to honor only one nationality and one religion – the almighty dollar. Abandoning turf wars, and ignoring ethnic differences, they accordingly formed strategic alliances motivated solely by profit.

Rogues’ Gallery

Waxey Gordon, aka Irving Wexler, reputedly earned his nickname because he could remove a man’s wallet from his pocket as smoothly as if it were covered with wax. On Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Gordon worked as a labor goon, strikebreaker, bookmaker, dope peddler, and extortionist. He was repeatedly arrested and convicted. Waxey’s bootlegging career began with a loan from Rothstein. By 1925, Gordon was a beer producer and one of the East Coast’s biggest suppliers. He bought hotels, produced Broadway shows, and rented a ten-room apartment on New York’s West End Avenue, complete with five servants. In 1930–1, his income exceeded 1.6 million dollars, on which he paid a grand total of ten dollars in taxes. Convicted of tax evasion, he was sentenced to ten years in prison and fined eighty thousand dollars. In 1951, at age sixty-three, Gordon was convicted of selling dope. He died in prison in 1954.

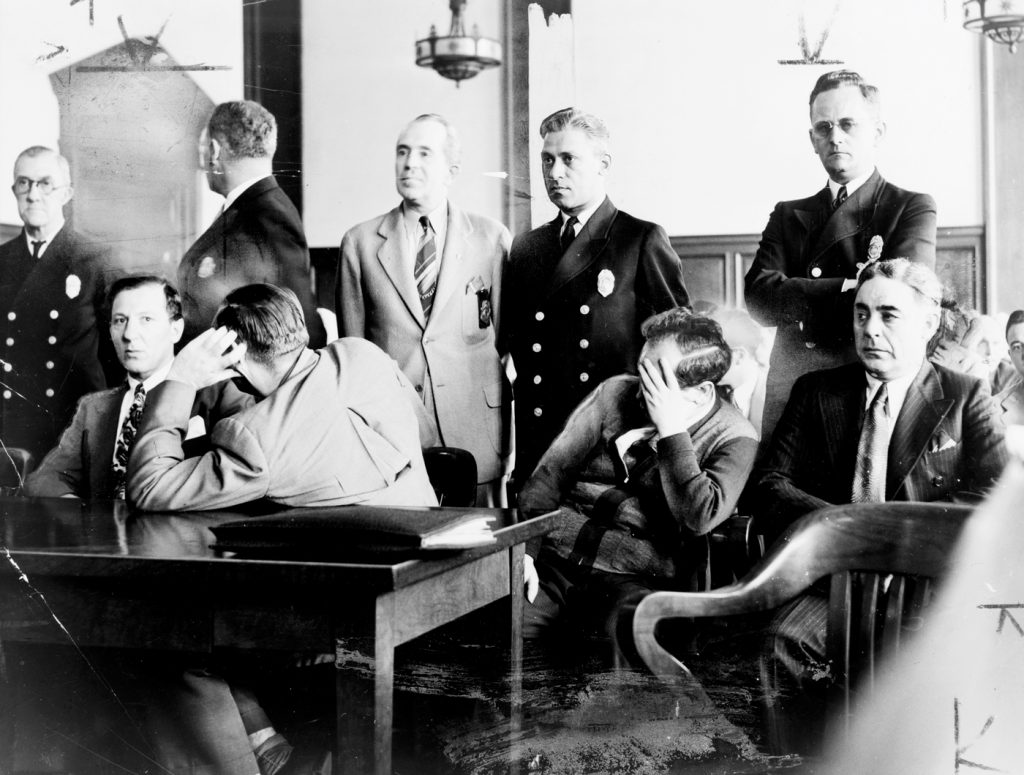

Photo by Al Aumuller, Library of Congress

Photo by Al Aumuller, Library of CongressSeated, left to right, Lepke Buchalter, Mendy Weiss, Farvel Cohen, and Louis Capone during jury selection in their murder trial, August 1941

Born in 1902 to a German-Jewish family, Dutch Schultz was one of the flakiest but most cold-blooded gangsters of the Prohibition era. Few liked or respected him, even among his own men. Nicknamed for a particularly vicious member of a turn-of-the century Bronx gang, Schultz employed a simple method of eliminating rivals: he murdered them. By the age of thirty, he was one of New York’s major racketeers, running illegal businesses worth more than twenty million dollars. He controlled all the beer in the Bronx, dominated labor unions and bookmaking operations, and extorted large sums from New York restaurants. In 1935, New York prosecutor Thomas Dewey began investigating Schultz. Dutch vowed to kill him. Lest Dewey’s murder bring the federal government down on all of them and wreck their rackets, Schultz’s cronies decided to liquidate him first. On October 23, 1935, Schultz was dining with his two bodyguards in Newark’s Palace Chop House. He stepped into the men’s room just as two contract killers, Charlie “the Bug” Workman and Mendie Weiss, sprayed Dutch’s men with gunfire. Workman then went into the bathroom and shot Schultz as he stood at the urinal. Dutch made it to the hospital in time to ask for a priest, who baptized him and administered the last rites before he died.

Meyer Lansky and Ben Siegel were lifelong friends. Born in Poland in 1902, Lansky came to the United States with his parents when he was ten. Despite leaving school at age fifteen, he remained an avid reader. Siegel was born in New York in 1905 and evolved into the archetypal movie mobster: handsome, hotheaded, ambitious, and ruthless. When angry, he actually glowed with rage. He was said to be “bugs,” slang for crazy, because of his reckless, violent nature; hence his nickname, “Bugsy” – which of course no one dared use to his face.

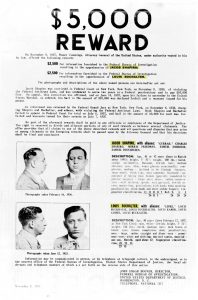

New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of Congress

New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of CongressJacob Shapiro and Lepke Buchalter in a “wanted” poster dated July 1937

Brains and Brawn

Lansky’s brains and Siegel’s brawn made a fearsome combination. In 1921, these teens recruited expert gunmen and began transporting liquor for bootleggers, delivery guaranteed. They also supplied mobsters with stolen vehicles and drivers, resorting to violence, intimidation, and even murder. By 1928, the Bugs and Meyer Mob, as the police called it, was selling protection to nightclubs, working for Italian mobsters Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello, muscling in on labor unions, and dabbling in armed robbery and narcotics. Lansky died of cancer in 1983. Siegel was not so lucky: a gunman knocked him off in 1947 in the living room of his girlfriend’s Beverly Hills mansion.

Louis “Lepke” Buchalter was born on the Lower East Side in 1897. His mother nicknamed him “Lepkele,” an affectionate Yiddish diminutive. As a result of various marriages, there were eleven children in the Buchalter household, but only Lepke went bad. He quit school at age fifteen and teamed up with Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro, a loudmouthed, two-hundred-pound enforcer. The two men remained close associates for thirty years. Lepke’s forte was labor racketeering; his thugs extorted millions. Aside from guns, their weapons included acid, fire, bludgeons, blackjacks, knives, and ice picks. The few brave enough to actively oppose the gang or report its activities to the police paid a price calculated to deter others. If these “sneaks” were lucky enough to escape assassination or disfiguring acid burns, attacks on their homes and families were the least they could expect. By 1930 Buchalter dominated a wide assortment of industries and unions in New York, including bakery and pastry drivers, milliners, garment workers, the shoe trade, the poultry market, the taxicab business, motion picture operators, and fur truckers. Lepke was also one of America’s largest importers and distributors of heroin, cocaine, and opium. In 1944, he was convicted of murder and electrocuted. He remains the only American crime boss to die in the electric chair.

-

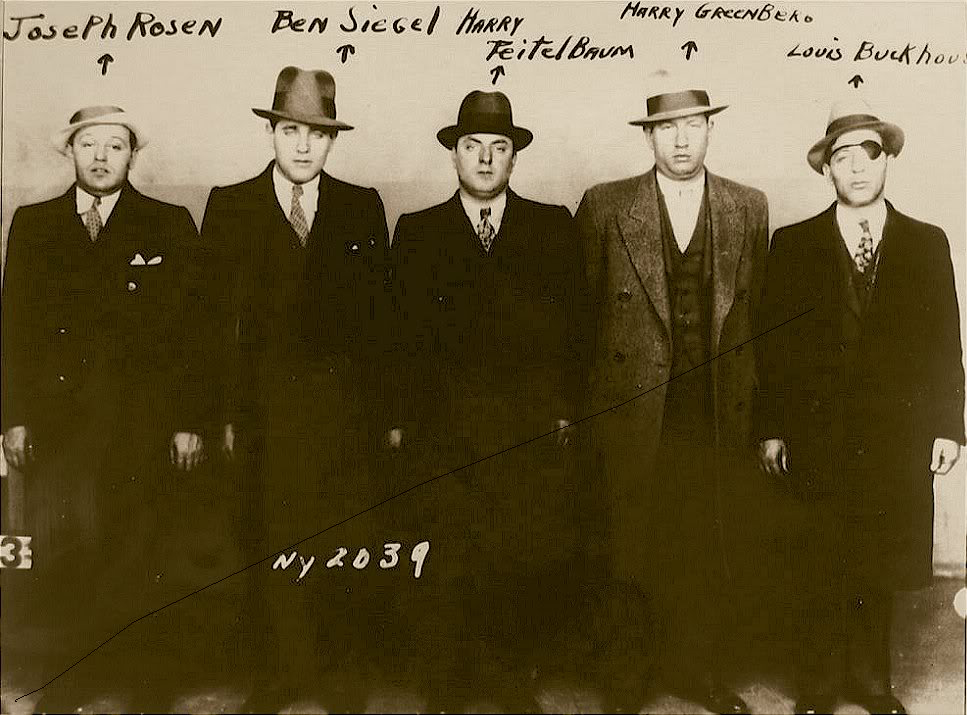

-Bugsy Siegel and his men in a mug shot taken during the Hotel Franconia raid, November 1931. Arrested under the infamous “Public Enemy” law, the gangsters were later released for lack of evidence of criminal intent. At the hotel, the Italian and Jewish Mafiosi reputedly entered into a cooperation agreement

Following Rothstein’s advice, these Jewish mobsters set aside ethnic issues and worked with their Italian counterparts, particularly Luciano and Costello. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, they allegedly carved up the country into territories, each to be ruled with impunity by its own crime czar. To this end, in 1931 Lansky organized a meeting of East Coast mob bosses at New York’s Franconia Hotel. According to Siegel, all agreed that “the Yids and the Dagos would no longer fight each other.”

No Clear Profile

The average New York mobster was a Jew of eastern European descent, primarily Russian or Polish. Most of these gangsters were born in the United States or arrived as small children. Most grew up traditional rather than strictly Orthodox; their parents lit Sabbath candles, kept a kosher home, and attended High Holy Day services. Most of the men never finished high school and were the only criminals in the family. Interestingly, they often spoke Yiddish among themselves, and slang such as kosher (trustworthy), yentzer (cheater), schmeck (drugs), and schmear (bribe) became part of the underworld lexicon.

Photo: Al Ravenna, Library of Congress

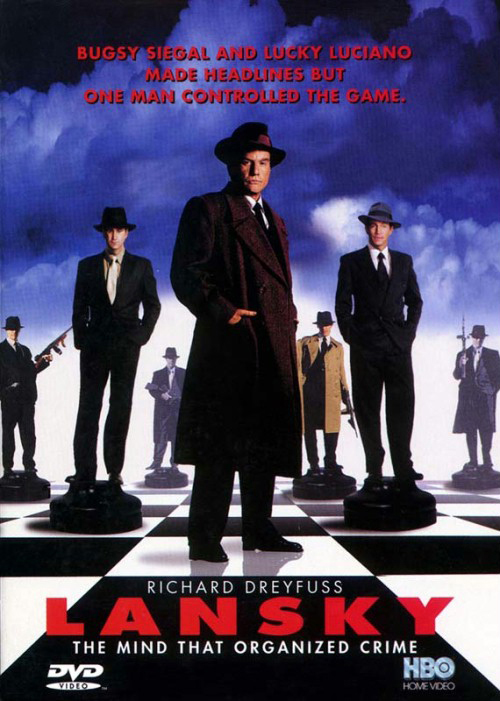

Photo: Al Ravenna, Library of CongressPoster from the film Lansky, 1999 Below, Meyer Lansky in 1958

What made these Jews turn to crime and even murder? Meyer Lansky said he did it because he grew up poor and never wanted to endure poverty again. Yet most of his cohorts came from working-class backgrounds, and a few (notably Arnold Rothstein) were raised in middle- or upper-middle-class and even wealthy homes. So what was the motive? Perhaps anti-Semitism. In 1920s America, Henry Ford published and distributed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion; universities and trade schools restricted Jewish enrollment; and Jews faced discrimination both professionally and socially. Blocked from respectable avenues to success and status, a growing number pursued alternative routes to fame and fortune through sports and entertainment. And some tough Jews may have been angry enough at American society to fight back with crime.

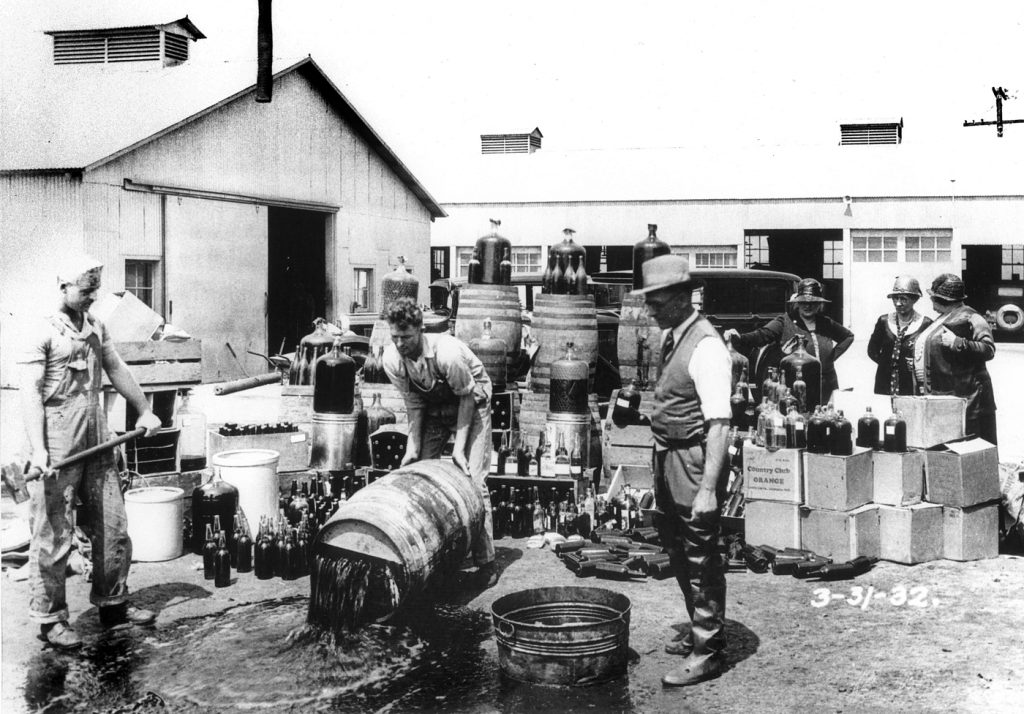

Photo courtesy of Orange County Archives

Photo courtesy of Orange County ArchivesOrange County sheriff’s deputies pouring away illegal alcohol, Santa Ana, California, March 1932

Generally, however, Jews turned to illegal activity because they wanted money, power, and prestige – and fast. Those lacking high school diplomas had limited options. For many of these young men, hard work was for “suckers.” Crime seemed more glamorous than the tedium of study or the drudgery of working long hours in a shop or factory. Criminal involvement has historically served as a ladder of mobility for the uneducated and violent. Prohibition greatly raised the stakes – and the level of violence – offered by a life of crime.

Shame and Adulation

The Jewish community expressed ambivalence toward the gangsters in its midst. On the one hand, law-abiding Jews were afraid and ashamed of these men; the Jewish hoodlum epitomized the “bad Jew,” who would bring down onus and hatred on the entire community. Jewish parents worried that their sons looked up to these felons and might emulate them. Rabbis fulminated from their pulpits, denouncing crime as contrary to Jewish values and warning that it would increase anti-Semitism. And Yiddish editorials decried the gangsters for disgracing and endangering the Jewish people.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division“Lefty Louie” Rosenberg and “Gyp the Blood” Horowitz (seated, left to right) with others implicated in the murder of Herman Rosenthal, proprietor of an alleged casino in New York City

Nonetheless, respectable Jewish leaders sometimes utilized Jewish criminals. In 1926, a major garment-district strike shook New York’s Jewish community. Jewish employers hired the gangsters to beat up strikers and disrupt picket lines, and the Jewish workers’ union fought back by employing their own thugs. Not surprisingly, the brutes on both sides worked for Arnold Rothstein.

On the other hand, the average Jew secretly admired the gangsters because they were unafraid of non-Jews and gave as good as they got. Lansky once told an interviewer, “I never got on my knees for any Christian.” Among youngsters growing up in Jewish neighborhoods, the Jewish mobster was their fearless protector. New York–born talk-show host Larry King has admitted that when he was a boy, “Jewish gangsters were our heroes.” As Chicago mobster Davey Miller once explained, “Maybe I am a hero to the young folks among my people, but it’s not because I’m a gangster. It’s because I’ve always been ready to help all or any of them in a pinch.”

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs DivisionArthur Flegenheimer, better known as Dutch Schultz, in 1935. Schultz was mown down as ruthlessly as he murdered others

Prohibition ended in 1933, drying up a lucrative source of income for New York’s Jewish mobsters. The more talented and creative among them found other ways of making a killing (as it were). Meyer Lansky focused on gambling in the United States and Cuba. Lepke Buchalter dominated New York’s garment industry. And Bugsy Siegel moved to Hollywood to extend mob influence over the film industry.

Most of these men’s lives ended badly. Siegel once remarked that one should live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse. Most Jewish gangsters did live fast and die young. Dutch Schultz was gunned down at age thirty-three, Siegel at age forty-one, and Lepke Buchalter went to the electric chair at age forty-seven. In the end, not one of them made a good-looking corpse.