Enter Ganat

When the smoke cleared after the Six-Day War, Israel’s government had to make major strategic decisions about the areas conquered. As the gunfire ceased in the Old City in those euphoric days of its liberation, the first voices were heard calling its exiled Jewish population home.

Yet Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek and Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir dreamed of a total break with the past. They planned an artists’ colony and museums in the rebuilt quarter. Indeed, the first Jews to settle there were not the original, mostly ultra-Orthodox population, but artists. Painter Nahum Arbel and curator Elida Merioz each bought dilapidated Arab homes as soon as the fighting died down. Both Arbel and Elida left within the first year, however, and the idea of an artistic center was dropped.

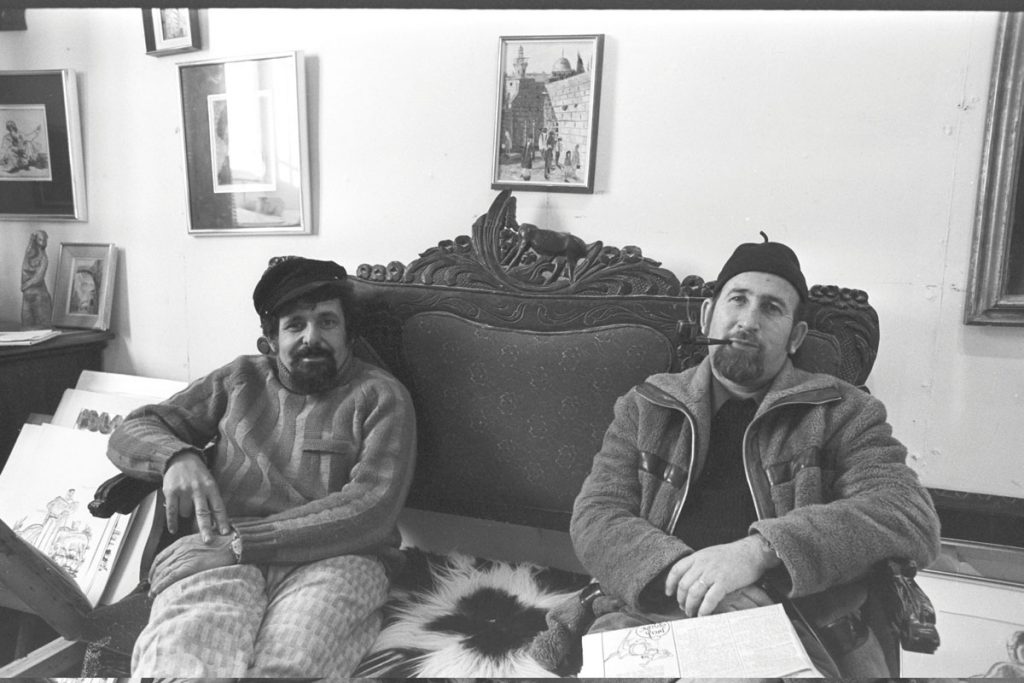

The first pioneers to return to the Jewish Quarter were artists, though Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek’s vision of an artists’ colony – like that in Safed’s Old City – failed to materialize. Artist Nahum Arbel (left) with Elida Merioz in the latter’s art gallery in the Jewish Quarter, 1973

Interior Minister Moshe Haim Shapira of the National Religious Party had a different vision. He saw the return of Jews to the Jewish Quarter as a settlement imperative to be carried out as fast as possible. Into that vision stepped the Ganat groups.

Urban Pioneering

Two of the greatest challenges facing the young State of Israel involved making the army part of the social fabric and filling the country’s empty spaces with housing and employment for the millions of immigrants flooding in. In 1948, pioneer youth movements approached the prime minister and acting minister of defense, David Ben-Gurion, with a promising proposal to attack both fronts at once: movement members would serve together in the army, providing the stable, fairly homogeneous groups needed to create settlements. Ben-Gurion promptly set up Nahal – a Hebrew acronym of “Fighting Pioneer Youth.” The National Service Law passed at the end of 1949 included the option of living in a Nahal cooperative, combining agricultural training and employment with military service.

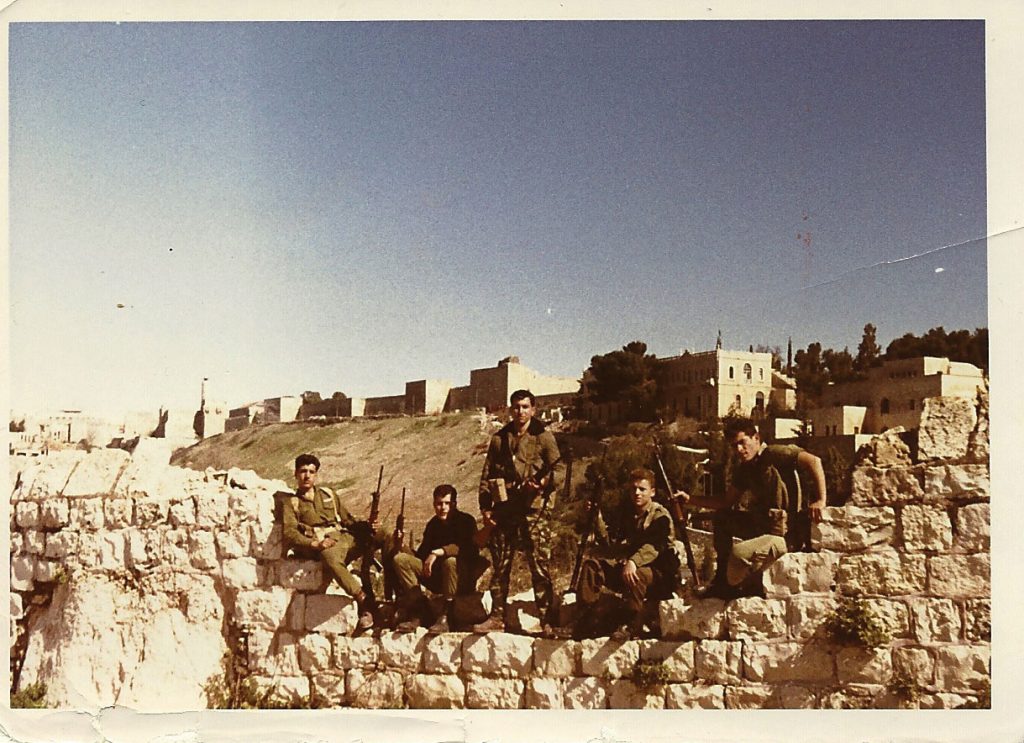

Armed Nahal soldiers stand guard above Ben Hinom Valley, beneath the Old City walls

The state’s second decade saw a substantial increase in the proportion of young people studying in vocational high schools, and growing numbers of army recruits were therefore already equipped with a profession when they enlisted. The national religious sector had its own such school, Boys’ Town Jerusalem, where students learned carpentry, mechanics, printing, and electrical engineering alongside traditional Jewish subjects.

Rabbi Yaakov Lishansky, the headmaster, noticed that at the end of his graduates’ army service, many weren’t going back to the professions they’d trained in. So he asked the Defense Ministry to make it possible for recruits to continue developing their professional skills alongside their military training. In 1964 an experimental Fighting Pioneer Youth for Industry (Hebrew acronym: Ganat) program was established. The first group – composed of Boys’ Town graduates – was named “Bezalel” (after the artisan of the biblical Tabernacle), but subsequent ones were known as Ganat A, Ganat B, and so on.

Like their Nahal counterparts, the Ganat groups were kibbutz-like cooperatives. They settled in border areas chosen by the Defense Ministry, putting their vocational training to use in local industries. As the original request had come from a religious high school, the National Religious Party selected the groups’ precise location and provided direction, support, and training – just as the kibbutz and moshav movements did for the Nahal corps.

Ganat Bezalel was the guinea pig. If this first group demonstrated the viability of replacing agriculture with industry as the cooperative’s objective, similar programs would be created for secular vocational-training graduates.

On Mount Zion

When Ganat Bezalel was formed, Jerusalem was still divided, and its members were stationed on Mount Zion (making them the first pioneer group in Israeli history to be posted inside a city). Despite rising security tensions, Mount Zion remained a popular pilgrimage destination. With the Old City under Jordanian control, David’s Tomb was the only accessible holy site in the vicinity. Adjacent to the tomb was the President’s Room, used mostly for state ceremonial purposes, and across the courtyard was the Chamber of the Holocaust – the country’s first Holocaust museum – established by the Ministry of Religious Affairs.

Mount Zion during the 1950s, including David’s Tomb, the President’s Room and the Holocaust Museum

Ganat A and B settled on Mount Zion before the Six-Day War. Their members came not just from Boys’ Town but from vocational yeshiva high schools such as Kfar Avraham, near Ashdod; Kfar Chabad, near Lod; and Torah and Craftsmanship in Tel Aviv. Ganat C was the first to incorporate graduates of the Mizrahi girls’ vocational school and religious girls doing national service rather than joining the army.

Immediately after the Six-Day War, Nahal had to place its recruits along the state’s new borders. Most members of Ganat C, the fourth industrial Nahal group, had just completed their military service in the 50th Nahal Battalion. They’d fought near Beth Shemesh during the war and expected to start their civilian phase on Mount Zion. But in newly reunified Jerusalem, that location no longer needed protecting.

Meanwhile, the Old City awaited a renewed Jewish presence. Interior Minister Moshe Haim Shapira was ready and waiting to provide it, and Prime Minister Levi Eshkol supported him wholeheartedly. Dr. Samuel Zangwill Kahane, director-general of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, was among those pushing to send in the Ganat group. Eventually, Moshe Netzer of the Defense Ministry’s Department for Youth and Military Pioneering gave his consent, and the youngsters were on their way.

Back to Basics

That summer, two months after the Six-Day War, the first members of Ganat C moved into an abandoned ruin on Sha’arei Shamayim Street – today Gilad Street – in the Old City. By February 1968, it was habitable, and the rest of the group – thirty men and ten women – joined them.

Conditions were extremely difficult. The Jewish Quarter had been largely demolished by the Jordanians, so basic amenities such as water, gas, and electricity had to be provided anew. The Jewish Quarter Reconstruction and Development Company had yet to be founded, so the group spent the first weeks just organizing basic living space.

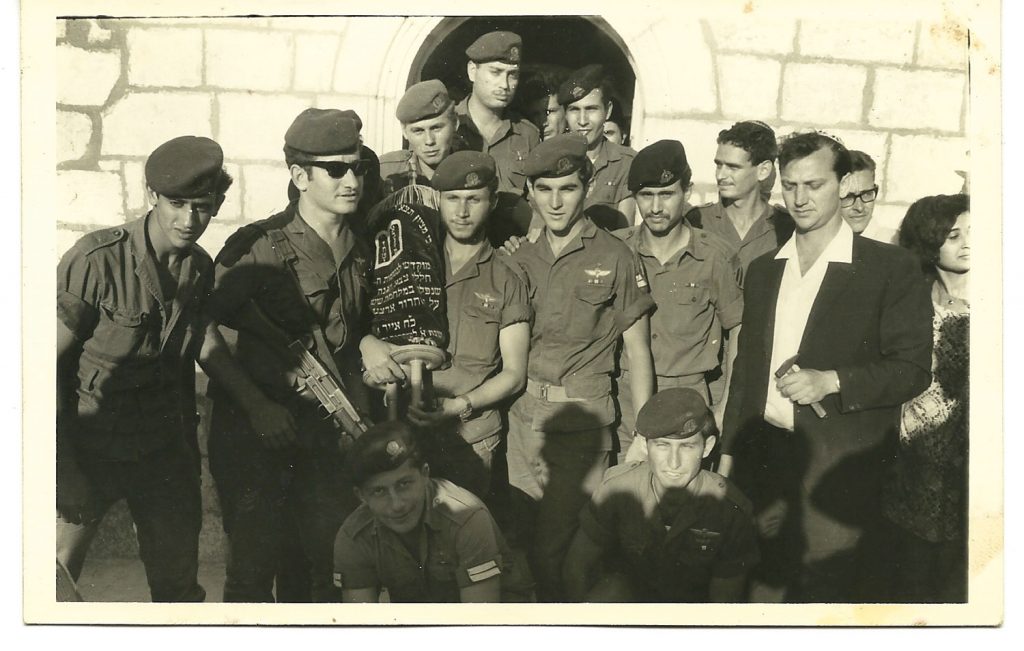

Members of Ganat C with the Nahal insignia in the entrance hall of their accommodations in the Jewish Quarter

“When I arrived,” recalled Gila Zagdon, who joined the group in autumn 1968, “everything was destroyed. Not a single building was fit to live in. When [my husband] Shmuel and I decided to get married, my father asked him, ‘Where do you think you’re taking my daughter?’”

All the group had to start with were a few sticks of furniture and basic kitchen utensils supplied by Boys’ Town. Nonetheless, these young people felt the entire Israeli public behind them when they set up house in the Jewish Quarter. “Everyone tried to help. Crowds of people were streaming down to the Western Wall every day, stopping by to express their support,” Yitzhak Mendelssohn explained. “It seemed like the Messiah was just around the corner. There was such euphoria; the joy, and the feeling that we were involved in some superhuman process, was indescribable.”

Settling down, however, was only half the story. As cooperatives, Ganat groups had to support themselves, with a little help from the National Religious Party. Ganat C divided up into work details according to members’ various professions. Some worked in a printing press set up on Mount Zion by the first Ganat group. (The idea of relocating the workshop to the Old City proved impractical.) The coop’s carpenters and metalworkers were often unemployed, while a third contingent worked in Israel Military Industries, commuting to the center of the country.

Most of the women dealt with cooking and laundry, which wasn’t easy under the circumstances. Zagdon remembers preparing meals for dozens over a single gas burner in a kitchen two meters square. With no housewares store in the Old City, the women took turns transporting goods from the nearby Mamilla neighborhood or the more distant Mahane Yehuda market.

Good Neighbors

Soon after Ganat C established itself in the Jewish Quarter, its base was named Hitnahalut Moria (Moria Settlement), after the biblical Mount Moria (better known as the Temple Mount) close by. The Defense Ministry had requested that group members, now civilians, not be defined as Nahal soldiers, and that their base not be described as a Nahal outpost, so the term hitnahalut was coined instead.

A short while after the pioneers moved into the Jewish Quarter, a national religious academy opened there – the Kotel Yeshiva, named for the nearby Western Wall. A few highly politically motivated Jews moved into the neighborhood too, including Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Segal, founder of the Brit Hashmonaim religious Zionist movement (active mainly from 1937 to 1949).

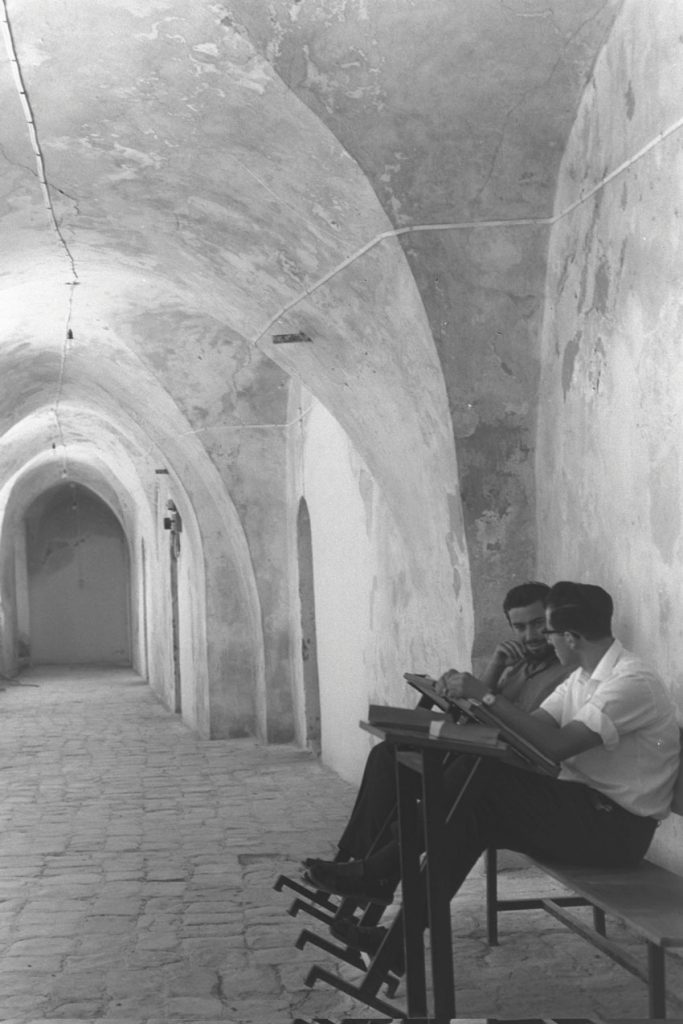

The singsong of Talmudic learning returns to the Old City. Two students from the Kotel Yeshiva, June 1968

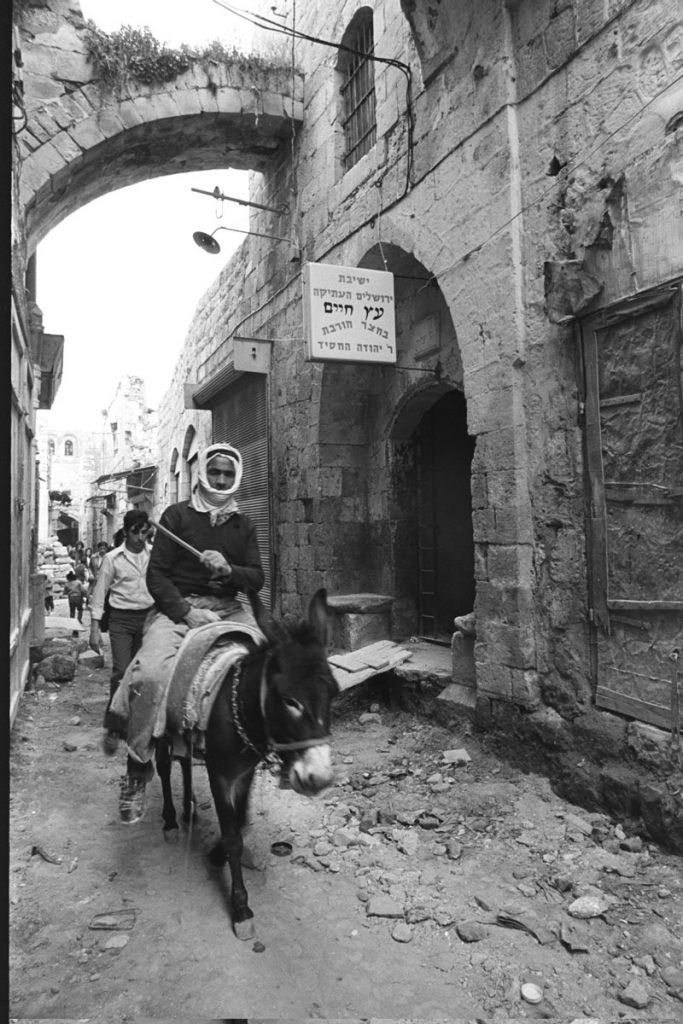

In July 1968, the Knesset established the Jewish Quarter Reconstruction and Development Company, and urban planning began. Change came slowly, however. Due to the narrow alleyways and general chaos, rubble could be carted out only by donkey. The resulting construction delays convinced Arab inhabitants of the Old City that the Jewish presence wouldn’t last.

“In the first years, bricks and Molotov cocktails were thrown into the Jewish Quarter. The Arab population assumed it was only a matter of time before the Jews lost their hold on the Old City,” says Mendelssohn, director of Moria. Arabs still lived and worked in the Jewish Quarter, and the new Jewish arrivals felt insecure. People left the coop building only in pairs. Though they wore army uniforms and carried guns when on guard duty to give an impression of strength, the border police had taken charge of the area’s security immediately after the war.

Neighborly relations developed between some coop members and Arab residents of the Old City, while others were suspicious and hostile. Arabs passing the ruined entrance to the Hurva Synagogue, in which the kabbalistic Etz Haim Yeshiva temporarily set up shop. March 1972

Though many local Arabs were hostile, some behaved otherwise. Members of Ganat C fondly recall the elderly Arab who came up to them and began talking excitedly in Hebrew and Yiddish. He led them to Torah scrolls that the quarter’s original Jewish inhabitants had hidden in a cistern underneath the Hurva Synagogue before their forced departure. Why had they trusted him with this, their holiest secret? His friendship with the Jewish residents was allegedly based on a business partnership, under which he heated up their Sabbath stews. In recognition of his faithfulness, the government left his market stall intact within the area zoned for Jewish building. “You can still find his grandson there today, on Ha-yehudim Street, selling ‘bagels,’” Mendelssohn adds.

Relations between the two populations stabilized in the early 1970s. “Once the Arabs realized the Israelis were here to stay, bringing tourists and tourism with them, the violence ended,” claims Mendelssohn. “They understood the business potential.” That was when he started taking tourists into the Muslim Quarter as well.

“From about 1970,” his wife Rachel continues, “I used to walk around there on my own, bringing shoes to be repaired and running other errands. I came home at night through the Arab souk without a touch of fear.” A year later, she and two friends even studied Arabic in the Sisters of Zion Convent. “I had an agreement with the grocer next door,” Rachel says with a smile. “Every time I bought something, he told me what it was called in Arabic, and I taught him the same word in Hebrew.”

Pairing Off

Ganat C’s primary mission was to bring Jewish life and culture back to the quarter. Part of the coop building was reserved for meetings and cultural gatherings. “Crowds came every night, from all across the political spectrum,” Mendelssohn recalls. “Every week the group organized an evening program, and often there were more visitors than actual members.” In the post-’67 euphoria, barriers crumbled as radical leftists rubbed shoulders with settlers in Moria’s clubroom.

Among the first coop couples were Shmuel and Gila Zagdon. As a matter of principle, they wed in the Jewish Quarter. To make room for all the guests, the group strained to clear the large square outside the original almshouses (Batei Mahseh) in the Jewish Quarter. “It was over a year since the Ganat group had moved in, but the square was still a mess,” Gila says. “There wasn’t even space to walk around it freely.” It would be two more years before the area was paved. Nonetheless, the wedding proceeded. Boys’ Town provided tables and chairs; food came from Zonnenfeld Catering, then Jerusalem’s lone caterer.

“The sounds of joy, of bride and groom, will once again resound in Judah and Jerusalem,” wrote Jeremiah the prophet. Yitzhak and Rachel Mendelssohn’s wedding in the Jewish Quarter

The spate of weddings in the Jewish Quarter continued as students of the Kotel Yeshiva followed the trend set by the Ganat group. By now the Jewish Quarter Reconstruction and Development Company was up and running, and the young couples moved into the first renovated apartments – each just twenty meters square.

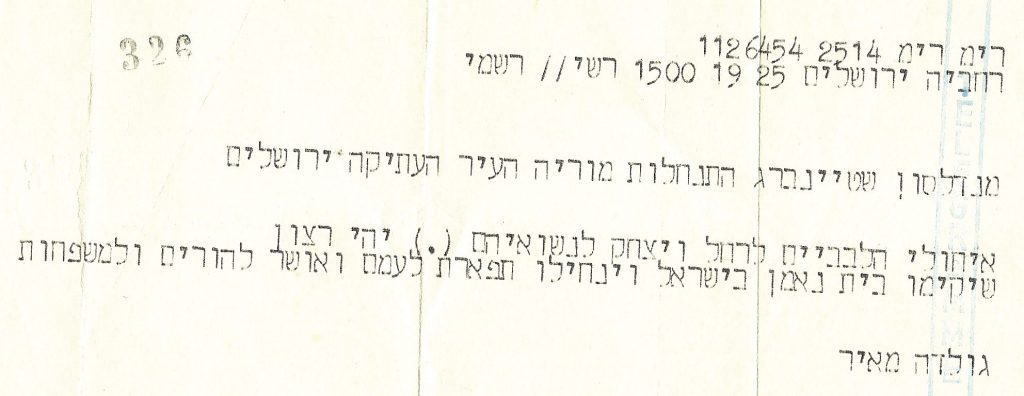

The Israeli government took an active interest in resettling the Jewish Quarter, excited by each milestone in its revival. Telegram from Prime Minister Golda Meir to Rachel and Yitzhak Mendelssohn on their wedding day

Children soon arrived – the first Jews born within the Old City since its capture in 1948. The municipal kindergartens were too far away, so the mothers started their own in the clubroom. The yeshiva students’ wives brought their children too. “Every day we’d fold up the playpens and store the equipment at the end of activities, putting the room back together,” recalls Gila. “The children usually played near Batei Mahseh, and for a real treat we walked all the way to Independence Park [outside the Old City]. The green, open spaces were heaven for them!”

In 1971, a pediatrician finally moved in near the coop building, and the young mothers no longer had to walk all the way to the clinic on Strauss Street, in the new city, whenever their children needed a doctor.

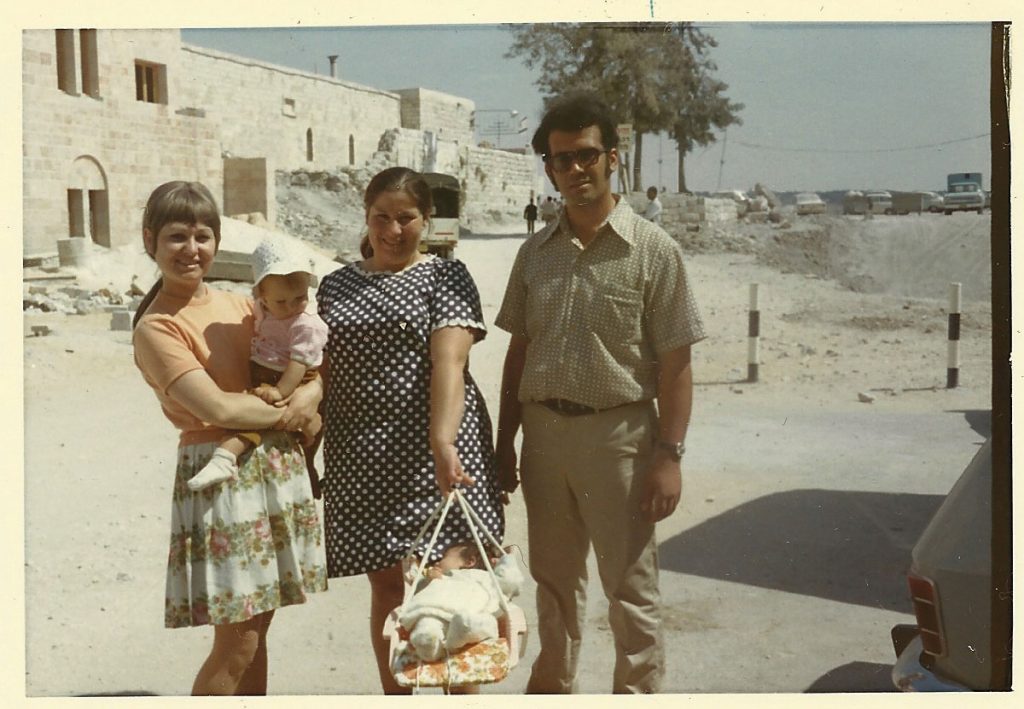

Afternoon stroll. Ganat members walking with their children in the newly rebuilt quarter. Yossi and Mira Eliav with their eldest son, and Rachel Mendelssohn with her daughter

An End – and a Beginning

Though the members of Ganat C had moved into permanent housing, joined by Ganat D and E, their financial state was precarious. “Those of us who worked in Israel Military Industries soon became aware of the income gaps between us and the other members of the cooperative,” explains Yitzhak Mendelssohn. “As some took on new positions or were promoted, they began to leave.” The economic divide undermined the coop’s foundations. In addition, “The fact that some members held jobs outside Jerusalem totally contradicted the original idea of working in local industry. Alternatives were proposed – such as setting up an industrially based moshav near Modi’in or on the Golan Heights, where we’d all earn the same.”

Another prophecy was fulfilled as Jewish children played and laughed in the streets of Zion. Ganat kids cool off on a hot summer’s day

Institutional support was also lacking. “Nahal cooperatives were backed by the kibbutz and moshav movements. On every new kibbutz, members were trained and mentored by families from older, similar communal farms. We were sorely lacking charismatic personalities who could provide that kind of guidance. Had we been preceded by a tradition of industrial cooperatives, producing experienced people who could advise us, we might have established ourselves more firmly in the Jewish Quarter,” says Mendelssohn with slight disappointment. “The Mizrahi Workers’ Party (as the National Religious Party was then widely known) was full of good intentions but lacked the resources to help us,” he sums up.

There was an attempt to move everyone to Atarot, an industrial area outside Jerusalem, but it came to nothing. Certain Ganat members stayed in the Jewish Quarter, where some still live.

Today, with the Jewish Quarter thriving and its centuries-old landmarks rebuilt, it’s hard to remember that fifty years ago it lay in ruins, and a handful of young men and women brought it back to life. Moria didn’t manage to create a cooperative settlement along the lines of an urban kibbutz, but its members did resettle the Jewish Quarter, despite all the hardships along the way.

Two of the Jewish Quarter’s original inhabitants, forced to abandon their home in 1948, revisit the ruins of the Hurva a few days after the Six-Day War. The area was unrecognizable both after the Jordanians had destroyed it and after the Israeli government rebuilt in the seventies and eighties