Tension

In early September 1908, the chief of the New York City Police Department published an article stating that Jews numbered about one-fourth of the city’s population but fifty percent of its criminals. New York’s Jewish population was then about one million – a large majority of hardscrabble immigrants from eastern Europe, who lived in the southern part of town, and a minority of affluent, long-time residents, mainly of German origin, who resided in the north.

The accusation was both false and anti-Semitic. A study produced by the Jewish community earlier that year had shown that crime was less prevalent among Jews than among New Yorkers at large – although the Jewish crime rate was higher than it had been in Europe, and the crimes committed were more diverse.

A mere fifteen days after the appearance of the article, Jewish immigrants had persuaded the police chief to retract his statements, admitting that they were based not on police statistics but on information provided by outside sources. Jews published various responses to the article. While the immigrants objected to the condescending attitude of the more established, uptown elements of the community and claimed that they should have taken a more courageous stand against the aspersions cast on their fellow Jews, they realized that they would be hard-put to deal with many pressing issues without the help of their more affluent brethren. The old-timers, in turn, preferred to work through less vocal channels, and accused the immigrants of over-reacting.

As the editors of one Jewish newspaper remarked, the Jews clearly lacked a central organization to speak and act on their behalf. Judah Leon (Leib) Magnes, a well-known Reform rabbi and activist, repeated this sentiment in a New York Times article. New York’s million Jews, he concluded, needed a permanent representative body to defend their rights and fight crime.

A United Community

These first glimmers of cooperation between New York’s “old” and “new” Jews radically altered both groups as well as the relations between them. The established community realized that notwithstanding the physical and cultural distance separating it from the immigrants, non-Jews would always lump the two groups together. The veterans would therefore have to begin relating to the immigrants as equals. The immigrants, for their part, understood that they needed the established community’s cooperation if they wanted to make use of its contacts and influence.

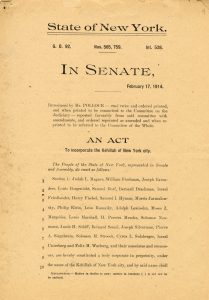

In February 1909, after five months of feverish discussions, representatives of no fewer than 222 Jewish organizations in New York adopted the constitution of “The Jewish Community of New York City,” or “the Community” for short. Religious and non-religious, Orthodox and Reform, Zionists and non-Zionists, greenhorns and veterans were united under the new structure. The driving force behind it – and its unchallenged leader – was the charismatic Magnes, who had family and social ties within many of the Community’s constituent circles.

Unlike the European kehilla, the New York Community was democratic, and membership was voluntary; after all, the idea of a religious community in which personal membership is imposed by the state was un-American. The Community was also much larger than any kehilla in Europe and came into being when the Jewish population had lost much of its religious and social homogeneity.

The Community’s goal was to solve the typical problems of an immigrant community whose traditional moral authorities – parents, teachers, and clergy – had lost most of their muscle. Its brief included issues such as poverty, backwardness, and crime, which it was supposed to tackle by reinforcing and Americanizing Jewish education; systematizing religious services – circumcision, kosher food certification, ritual slaughter, and synagogues, to name but a few; dealing with labor relations (in the garment industry, for example, workers and employers alike were largely Jewish); and establishing departments of philanthropy and vocational training.

A One-Man Organization

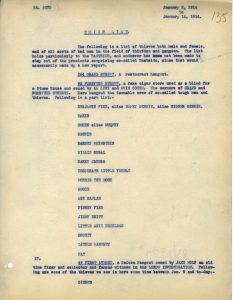

In 1912, however, a widely publicized murder changed the rules of the game. Hermann Rosenthal, a Jewish casino owner, had agreed to testify against a police officer who had been his undercover business partner but had betrayed him. Several days later, Rosenthal was murdered in midtown New York in broad daylight. The Community was shocked to discover that of all the criminals, collaborators, and witnesses involved in the affair, only two were not Jewish. It was clear to Jews of all persuasions that drastic action had to be taken to eradicate crime in Jewish areas. The Community established a “social morals bureau,” effectively a secret police force that gathered information about criminal activity – thefts, drug dealing, gambling, prostitution, extortion, and more – in the relevant parts of town. A meeting between Magnes and the mayor resulted in the appointment of a trustworthy police officer to receive Community reports of criminal activity and dispatch cops to arrest the perpetrators and shut down illicit businesses.

The method worked like a charm until the mayor died about a year later. Although the morals bureau remained active until 1917, the new mayor placed the city’s cooperation with the Community on the back burner. Furthermore, certain Community officials opposed making the bureau into a permanent arrangement, and Magnes found it hard to raise enough money to keep it running. To make matters worse, his pacifist views and objection to U.S. participation in World War I destroyed his popularity, to the extent that he was ostracized by the wider Jewish community, most of which favored American involvement in the conflict and feared accusations of disloyalty. Both the bureau’s activities and overall Community operation declined as a result, ending with the whole organization’s closure in 1922. Magnes emigrated to Palestine with his family and embarked on new projects, including the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Despite its relatively short lifespan, the Community’s legacy was considerable, not only in New York but in the organization of Jewish communal life throughout America. The Community also left behind two magnificent Jewish institutions that operate to this day in New York: the Jewish Education Committee and the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies.

Several years after Magnes moved to Palestine, the files containing much of the Community’s correspondence were sent to him. Today they form a significant part of the Magnes Collection at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People.