Armed with Brush and Rifle

Individualism is perhaps the most fundamental of artistic values. The artist’s individual expression is the linchpin of his creativity, so when his talents are harnessed by a regime or an institution, modern sensibilities expect them to be compromised, or at least limited. Communist art – and, arguably, religious art – are merely the first examples that come to mind. Arthur Szyk (pronounced Shick), who died just over sixty years ago, was quite the opposite of the cosmopolitan artist whose art sets him above the violent struggles of national loyalties. Unashamed of his people and origins, he never hid his Jewish identity, unlike many of his friends and colleagues. His art, as well as his life, was unabashedly devoted to his own struggle with the enemies of his people. But Szyk’s art was far from compromised. Perhaps just the opposite – his sense of mission inspired some of his greatest works.

Arthur Szyk (1894–1951) was born in Lodz, Poland, and although he eventually immigrated to the United States, he never lost touch with the land of his birth. Like many Jews, especially during the first half of the 20th century, he was somewhat itinerant, spending time in Paris as well as in Palestine. Despite strong ties to Poland, his heart was always in the east, and he unhesitatingly and repeatedly engaged in the struggle for a Jewish homeland.

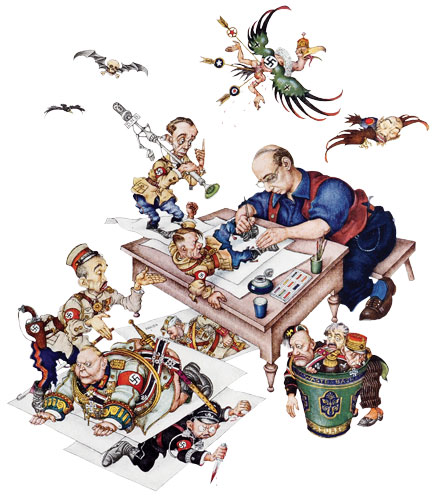

The frontispiece for Szyk’s book Ink and Blood (New York: Heritage Press, 1946). Hitler squirms as he emerges from under the artist’s pen; his propaganda chief, Goebbels, stands on the table holding a microphone; and Goering grovels on the floor. Mussolini, Petain, and Laval languish in the artist’s wastepaper bin

Szyk’s father, Solomon, was a well-to-do manager of a textile factory. His family was traditionally observant, and he was particularly proud of his lineage – he was descended from the illustrious Rabbi Yom Tov Lipmann Heller (1578–1654), author of the Tosfot Yom Tov commentary on the Mishna. Tragically, in 1905, he was blinded when a factory worker threw acid in his face during an uprising against the Russian Empire that came to be known as the Lodz Insurrection.

Arthur’s extraordinary artistic talent became apparent at an early age. He was especially drawn to biblical scenes. In 1909, upon the advice of the young prodigy’s teachers, his father sent him to study in Paris, where he was exposed to the latest artistic trends. But Arthur Szyk’s art was, to say the least, highly individualistic, unmarked by the modernism and surrealism of his day. The strongest influences on him were illustrated manuscripts, carvings, and paintings from the Middle Ages.

At age twenty, Szyk returned to Lodz and, extensive artistic endeavors notwithstanding, became deeply involved in Zionist organizations in the city. One such was Zamir, a choral society specializing in traditional and popular Jewish songs. Arthur joined a Zamir delegation to Palestine and visited Tel Aviv, which had been founded only five years earlier. Two newspapers, Hapoel Hatza’ir and an Arabic daily, interviewed the young artist, who expressed his delight at being able to walk the land of his ancestors.

The young artist befriended a number of Hebrew writers during his stay, especially the poet Yehoshua Shlomo Blumgarten, better known as Yehoash, the author of a Yiddish translation of the Bible. The two traveled all over the country, and Szyk also visited Yehoash at his home in the newly settled area of Rehovot, where the artist took his turn guarding the citrus groves. Attracted to the kibbutz movement, he spent time at Degania, the first such communal settlement, and some of his paintings immortalize day-to-day life on the young kibbutz. Szyk also spent many hours at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, sketching Jews of varied origin and from all walks of life at the holy site. He fraternized with students at the newly founded Bezalel Academy of Art and even taught there.

Szyk’s stay in Palestine was cut short by the outbreak of World War I. Forced to return home, he was drafted into the Russian army. He fought in the battle of Lodz, but managed to escape from the front in 1915 and spent the rest of the war as a civilian. This was a seminal period for Szyk. The first exhibition of his paintings was held in Lodz, including renditions of biblical figures and caricatures of Russian soldiers. He married Julia Liekerman in 1916, and in due course fathered a son and daughter.

In 1918, Poland gained independence after a century of partition by Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia. Many Jews hoped they would finally be granted equal rights. Reality could hardly have been farther removed from their expectations. In the ensuing Polish-Ukrainian War of 1918–9, Polish troops regaining the upper hand in Lemberg (Lvov) ran riot in the Jewish quarter, killing approximately one hundred Jews, injuring thousands, and destroying hundreds of Jewish businesses. In the wake of the pogroms, Szyk, the Polish patriot, renounced his Polish citizenship.

By 1921, Szyk was back in Paris, this time as a celebrated artist. His fully developed style is apparent in the lavish, full-color book illustrations he produced during this period. He maintained his contacts in Poland, painting his famous illustrations of the Statute of Kalisz, a charter of liberties granted the Jews by the Polish ruler Boleslaw, duke of Kalisz, in 1264. The work was exhibited in Warsaw, Lodz, and Kalisz. In Paris, leading galleries displayed his work. Szyk was at the height of his career.

While based in Paris, he traveled extensively, visiting Morocco, where he painted a portrait for the pasha of Marrakech, and Geneva, where he toyed with a commission from the League of Nations. He was invited to the United States to paint the likenesses of famous American historical figures, works for which he was granted a Congressional Medal of Honor in 1934. In the 1930s, as Hitler gained power in Germany, Szyk was working on an illustrated Haggada, in which the Egyptian persecutors of the Hebrews were sometimes depicted as Nazis. The artist moved with his family from Poland to England to oversee its publication in 1937.

He became involved in the American publishing scene as a result of his work as a political caricaturist, ridiculing the Führer and his expansionist ambitions, and the Szyk family eventually settled in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1940.

During World War II, Szyk enlisted his pen and brush in the service of the Allies. His drawings appeared in the New York Times, Colliers, and many other major publications. At the height of the war, Szyk was involved in the activities of the Bergson Group, led by the Revisionist Zionist Hillel Kook, then using the pseudonym Peter Bergson (supposedly to avoid embarrassing his illustrious rabbinic family). The group’s efforts had focused on aiding Ze’ev Jabotinsky in his struggle to liberate Palestine from the British Mandate, but the war diverted them toward raising public awareness of the plight of European Jewry and promoting illegal immigration initiatives. Szyk designed the logo of the group’s publication, Answer, and his cartoons helped to sway public opinion against America’s restrictive immigration policy and toward granting admittance to Jewish refugees. Szyk waged his own propaganda war against the Axis countries – Germany, Italy, and Japan – drawing dozens of caricatures later published in book form as The New Order, in French and English. Despite his high-profile activities promoting the Allied cause, Szyk was granted American citizenship only in 1948.

With his highly developed sense of political and social awareness, Szyk was always at the vanguard of activist movements, from civil rights to anti-McCarthyism. In 1951, he was accused of collaborating with communists and summoned to testify before a Congressional committee. Deeply offended by the slur cast on his patriotism – only months before, he had produced his largest illumination ever, of the American Declaration of Independence, for that year’s Fourth of July celebrations – Szyk suffered a heart attack soon after the investigation, dying later that year at age fifty-seven.

Painting with All His Might

Arthur Szyk invested heart and soul in his paintings, devoting every fiber of his being to the message he was attempting to convey. Not coincidentally, his artistic style drew extensively on the illuminated religious manuscripts created by monastic scribes as an act of devotion. Some view him as a direct continuation of the Jewish artists who illuminated holy books and decorated synagogue walls over the generations, although the range of books he illustrated is varied to say the least. In addition to illustrated versions of the biblical books of Esther (1925) and Job (1946), Szyk published illustrations for the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1940), for a collection of fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen, and for Charles Perrault’s Mother Goose nursery rhymes. It would seem, though, that he approached certain projects with almost religious devotion. Toward the end of his life, Szyk created a new illustrated version of the Scroll of Esther. At its beginning, he added a prayer of his own next to the traditional blessings:

Lord of the Universe, God of my forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob – whose name is not mentioned in this book that celebrates the victory of justice – to You do I devote the labor of my hands and heart, in all humility and modesty, with gratitude that You have made me a Jew.

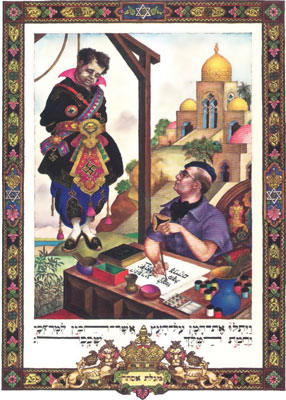

Illustration from Szyk’s megilla of 1950. Haman hangs from a gallows, swastikas adorning his uniform-like robes, while Szyk himself sits at his worktable, watching his enemy swing

Szyk’s first version of the book had focused on the traditional protagonists. Twenty-five years later, however, in 1950, the impact of the Holocaust brought to full fruition the artist’s identification of Hitler with the traditional archenemies of the Jews, already evident in his Haggada of 1937. In this later version of the book of Esther, Haman hangs from a gallows with swastikas adorning his uniform-like robes, while Szyk himself appears in the same illustration, seated at his worktable with his paints and brushes, watching his enemy swing as he writes the blessings recited after reading the megillah:

Blessed is He…who exacts the vengeance of Israel, His people, from all their enemies.

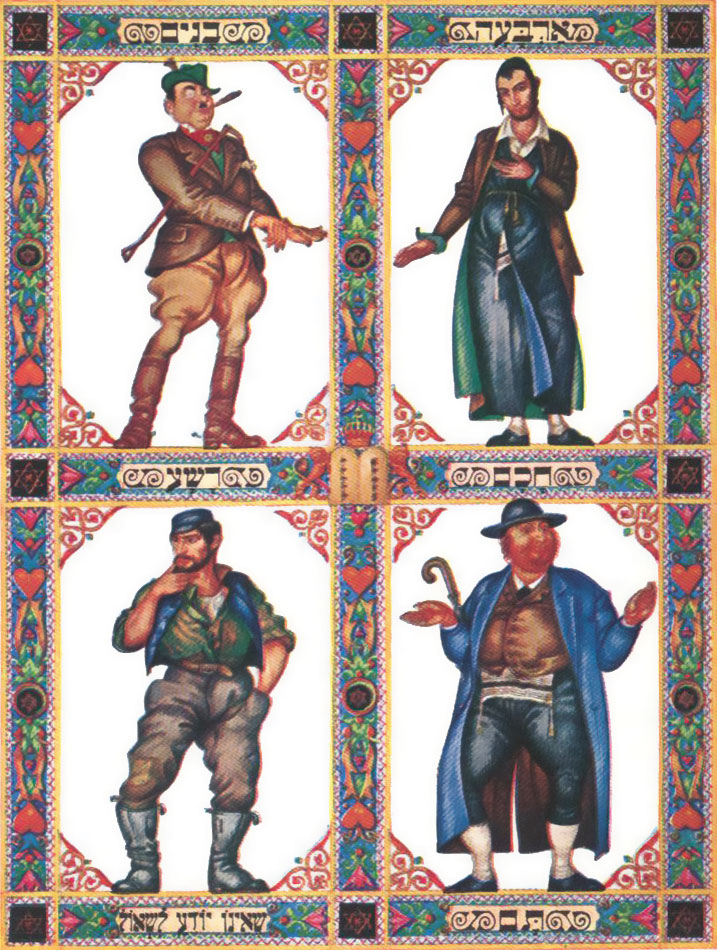

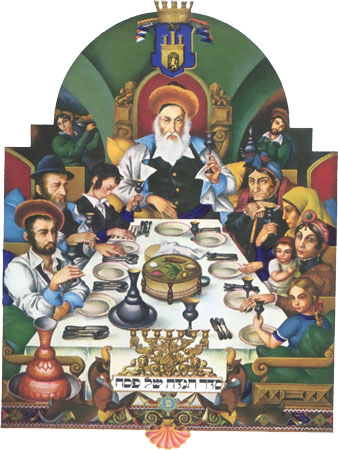

Szyk’s masterpiece was his Haggada. He began the project in Paris but returned to Poland to complete it, consulting rabbis regarding the many laws and customs associated with the holiday, so he could depict them accurately. In 1935, Szyk was invited to a Passover Seder in the home of Rabbi Eliezer Gershon Friedenson, a leader of the ultra-Orthodox Agudath Israel movement in Poland, with whom he had become friendly. Some of the people seated around that Seder table, including Rabbi Friedenson himself, are portrayed in the illuminated Haggada, immortalized despite their later incarceration and murder during the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. Szyk interspersed his Haggada with examples from his war on Nazism and fascism. In his highly contemporary illustrations of the four sons, he drew the evil son as a Nazi officer with a Hitler-like moustache. As the British government vacillated before declaring war on Germany, Szyk’s British publishers held up publication until he had painted over the swastikas decorating his Egyptian figures. The artist even added verses of redemption and salvation to the traditional text. The Hagadda featured an English introduction by Prof. Cecil Roth and an English translation.

A Royal Edition

The first edition of this deluxe Haggada bore a dedication to the community of Lemberg/Lvov, which helped fund its publication in 1939, just a few months before the war. Published in England under Szyk’s personal supervision by Beaconsfield Press, 125 copies were printed on vellum, each carrying a $500 price tag, an astronomical sum in those days. The goal was to create a foundation to cover the costs of printing a less expensive edition.

The first copy was dedicated to George VI, king of England, and is preserved to this day in the Royal Library in Windsor Castle. The Times enthused that it was “worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the hand of man has ever produced.” Legend has it that King George took his Szyk Haggada down to the bomb shelter with him during the German bombardment of London.

The war delayed distribution of the Haggada, and it was republished only in the 1950s. Massada Publishing purchased the distribution rights and issued a deluxe edition in a choice of silver or velvet bindings, with a more popular version produced in tens of thousands of copies.

Framing Independence

The establishment of the State of Israel was one of the most moving moments in Szyk’s life, evidently eclipsing his receipt of American citizenship only months earlier. His wife, Julia, recalls that when he heard the founding of the state proclaimed on the radio, he burst into tears. The artist created an illuminated version of the young country’s Declaration of Independence, as well as a decorative headline for its first official newspaper edition, in which the limits on Jewish immigration imposed by the British Mandate’s White Paper were officially abrogated. Szyk surrounded the text of the declaration with depictions of major events in Jewish history, with the traditional Sheheheyanu blessing, recited on special occasions, placed at the top. He used the same script he had used in his Haggada and book of Esther, enlarging it to emphasize two paragraphs:

Accordingly we, the members of the people’s council, representatives of the Jewish community of Israel and of the Zionist movement, are here assembled on the day of the termination of the British Mandate over the land of Israel and, by virtue of our natural and historic right and on the strength of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly, hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.

…placing our trust in the “Rock of Israel,” we affix our signatures to this proclamation at this session of the Provisional Council of State, on the soil of the homeland, in the city of Tel Aviv, on this Sabbath eve, the 5th day of Iyar, 5708, May 14, 1948.

Underneath the declaration, Szyk reproduced the names of the members of the Provisional Council as they appeared in the original document.

Szyk’s illuminated Declaration of Independence was distributed as a gift to the readers of Ma’ariv, then Israel’s most popular newspaper, and was framed and hung in thousands of homes. Although he received many accolades in his lifetime, including a street named for him in Tel Aviv, the Jewish artist for freedom could not have imagined a greater reward.

Popular But Pricey

The Szyk collector’s editions command hefty prices in the art world

In 1991, Rabbi Irvin Ungar founded the Arthur Szyk Society to promote the artist’s work. The society has held exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe –including Lodz, Szyk’s birthplace – but not as yet in Israel.

A new edition of the Szyk Haggada, including a biography of the artist and accompanying articles, was published by the society in 2008. In true Szyk tradition, this edition was also published in two versions: a luxury collector’s edition (eighty-five copies), priced at $15,000 each; and a more modest limited edition (215 copies), selling for $8,500.

Many of the figures seated around the Seder table pictured in Szyk’s Haggada were portraits of real people at a Seder he attended in Poland not long before World War II, in the house of Rabbi Eliezer Gershon Friedenson

Further reading:

Samuel Leib Schneiderman, Arthur Szyk: A Biography [Yiddish, Hebrew] (Tel Aviv: Y. L. Publishing, 1980);

Joseph Ansell, Arthur Szyk: Artist, Jew, Pole (Oxford, Portland, Ore.: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004).