This article was published in issue 52 | Nisan 5780 | April 2020

In early 1969, a very elderly man lay in a darkened hospice room in Jerusalem’s Katamon neighborhood. Almost nothing was left of him but skin and bones, but his eyes were ablaze, showing that he was still very much in touch with reality. None of his fellow patients dreamed that this withered figure was once a key player in one of the city’s greatest dramas in years.

Moshe Shapira was born in Jerusalem’s Old City in 1886. His maternal grandfather, Rabbi Mordechai, had arrived in the Holy Land in 1853. Euphemistically known all over Jerusalem as Big Rabbi Mordechai, this tiny man married his daughter off to Rabbi Yisrael Asher Shohat Shapira, who blew the shofar every Rosh Hashana for the renowned Rabbi Moshe Yehoshua Leib Diskin. (Previously the rabbi of Brisk, Diskin escaped Russia just before false accusations landed him in Siberian exile. Taking up residence in the Old City with his family, he became a bulwark in the Orthodox community’s resistance to secularism and modernization.

Moshe Shapira. Photo: Matanya

Moshe Shapira. Photo: MatanyaMoshe Shapira

Celestial Secrets

Ordained as a rabbi at twenty-one, Rabbi Arye Leib Gordon of Lithuania was strictly Orthodox but fascinated by science. He even studied chemical engineering at the University of Berlin. An autodidact in many areas, this young genius had published works on Hebrew grammar and was a compulsive book collector.

At some point Rabbi Gordon caught the Zionist bug, came to Ottoman Palestine as a pioneer, and taught Hebrew and arithmetic in Petah Tikva. Moving to Rishon Lezion, he worked as a chemist at the Rothschild vineyard, only to clash with Baron Edmond’s infamous clerks.

Rabbi Arye Leib Gordon

Rabbi Arye Leib GordonGordon settled in Jerusalem in 1899. Despite Talmud Torah Me’a She’arim’s staunch opposition to secular studies, this complex character was hired as administrative director. In his two years in this capacity, he crossed paths with Moshe Shapira – a bright-eyed, intelligent youth who seized every opportunity to cut class and chat with Gordon about Hebrew, philosophy, and – above all – science.

The two were particularly taken with Hiya David Halevi Shpitzer’s Nivreshet Le-netz Ha-hama Be-Zion (Illumination of the Dawn in Zion), published in 1898 (5658). Though the West divides the day into twenty-four hours, regardless of sunrise and sunset, both Jewish and Muslim prayer times are calculated by dividing daylight and nighttime each into twelve “seasonal hours,” so called because their length varies throughout the year. Shpitzer had devoted his life to ascertaining the exact time frame for the recitation of the Shema (“Hear O Israel”) prayer in Jerusalem: from the moment the sun’s first rays pierce the morning sky until midnight. He’d spent day and night recording the precise time of sunrise in the few places where the city’s hills don’t block the rising sun; in the Old City, on the Mount of Olives, and wherever else he could.

Rejecting “modern astronomy” (i.e., Galileo’s heliocentric theory, placing the sun at the center of the solar system), Shpitzer preferred the Copernican geocentric model, in which the sun revolves around the earth. After all, according to the heliocentric model, it takes eight minutes for the sun’s light to reach the earth, so when exactly is sunrise – when we see the sun’s light, or eight minutes earlier?

Gordon and Shapira read Shpitzer’s book over and over, debating whether he was right. They were just as intrigued by his science as by the halakhic question of how to define sunrise, the ideal time for morning prayer.

Shapira became obsessed with the matter, especially when Shpitzer published a sequel in 1903 – Illumination II: Ascertaining the Time of Twilight around the World. The climax came in 1906, when Shapira was already twenty, in the shape of Shpitzer’s Tikkun Luah De-nivreshet (Revised Table of Illumination). This pamphlet listed sunrise times throughout the year, complete with diagrams.

By now, Shapira had spent years reading scientific articles as well as Talmudic works on astronomy and calendrical calculations, including the complex writings of the Gaon of Vilna. Armed with his own measurements, observations, and experiments, the young man embarked on a new profession: building sundials.

The Clockmaker’s Career

Shapira constructed his first such device atop his yeshiva in Me’a She’arim, enabling fellow students to recite “Hear O Israel” at the exact moment of sunrise-. He spent long months on the roof setting up a sundial made of two precisely angled marble slabs. These efforts paid off, and Shapira’s contraption worked as long as the weather wasn’t too cloudy. Sadly, his success was short-lived: the marble pieces suddenly collapsed one day, smashing to smithereens. Shapira was almost as shattered as his sundial.

Luckily, however, news of his expertise reached Shmuel Levy, a wealthy American tailor bankrolling a new “high-rise” on Jaffa Road, just outside the Mahane Yehuda market. The complex was to include a study hall, synagogue, and new immigrants’ shelter, and Levy dubbed it Zoharei Hama (Emanations of the Sun). Perched atop the local watershed, the ambitious project soared over four stories high and was topped by a small tower – a real skyscraper by Jerusalem standards in those days. Hashkafa, a local religious newspaper, couldn’t conceal its excitement:

And in Jerusalem the Jews rejoice, for yet another institution has been added to the previous ones: on Jaffa Road, at one of the city’s higher points, a new structure has been built, towering over the entire city. Three stone floors have already been erected, plus two wooden attics above them, and the construction workers are still hard at work raising the building yet higher.

From the shape of the attics, you can tell that [the structure] isn’t meant to be residential, and anyone who sees it says it must be an observatory. But what do Jews have to do with stellar observations? Is their calendar not fixed and accurate? What do they care about the paths of the stars?

Rather, this sage and understanding nation is unlike all others, and its lookout tower has been built not [to study] the stars, heaven forfend, but for a much nobler purpose.

A new society has lately been founded here, for those who pray as the sun peeks over the horizon. As Jerusalem is surrounded by hills, it’s extremely difficult to calculate [that precise] moment. So a certain gentleman, an American tailor prompted by generosity, has built this structure.

When the building is finished, a rooftop flagpole will be equipped with a thin, copper plate attached to it, so that when the sun’s first rays emerge, they’ll illuminate the plate so that it shines out, informing all Jerusalemites that it’s time to pray with the sunrise. Fortunate are you, O Israel! (L. P., “A Watchtower,” Hashkafa, 11 Tammuz 5666/July 4, 1906, p. 4 [Hebrew]).

For 19th-century Jerusalem, the Zoharei Hama complex was a skyscraper. The building in 1905, before Moshe Shapira’s sundial was added Photo courtesy of the Zionist Archive

Levy was far from satisfied with this primitive arrangement, however, so he was delighted to hear of Shapira the clockmaker. The tailor ordered a sundial for Zoharei Hama’s top floor – both for the benefit of those rising early to pray and to indicate when the Sabbath began on Friday evenings. Shapira happily set about measuring, checking, planning, and calibrating, and in just three years (!), he’d erected an enormous sundial spanning the entire five-meter width of the building. Shaped like an inverted rainbow, it was stunning and amazingly accurate – but its edges blocked the two side windows on the fourth floor, which served as a study hall and synagogue.

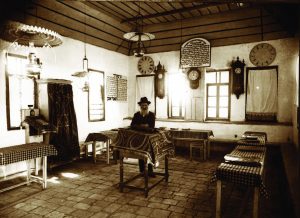

A synagogue chock-full of clocks. Notice the two clockfaces without hands, which were in fact merely covers for the gears of the clocks on the wall outside. Zoharei Hama interior, 1905

A synagogue chock-full of clocks. Notice the two clockfaces without hands, which were in fact merely covers for the gears of the clocks on the wall outside. Zoharei Hama interior, 1905

Sundial with a Smile

At the center of the sundial, starting at the same height as its upper edges, Shapira placed a gnomon – a carefully angled iron bar whose shadow moved around the clockface like an hour hand. Two smaller, ordinary timepieces were installed above the sundial in 1926, to tell time on cloudy days and in the winter. The right-hand clock showed the time in regular,Western hours, but the left-hand one’s Roman numerals displayed seasonal hours (sha’ot zemaniyot), so people could schedule morning and afternoon prayers. This clock was accurate only by day, dividing it into just twelve units from sunrise to sunset.

The sun's rays cast a shadow on the clock, showing worshippers when to gather for prayer. Zoharei Ham sundial. Photo: Aidyjerusalem85

The sun's rays cast a shadow on the clock, showing worshippers when to gather for prayer. Zoharei Ham sundial. Photo: Aidyjerusalem85The eyelike clocks and noselike gnomon accompanying the wide, semicircular sundial suggested a face, earning the whole installation the nickname “the smiling clock,” and its prominent position on Jaffa Road made it the most famous timepiece in Mandate Palestine. It’s still there today, though the building’s balcony was burnt by an electrical short circuit in 1941. The two clocks stopped working after the fire, and the gnomon was warped by the heat, so it now casts its shadow over the clockface half an hour late. But the overall apparatus remains an impressive sight, smiling down from its safe height at 92 Jaffa Road, opposite what used to be the Etz Haim Yeshiva by Mahane Yehuda. There’s even an ultra-Orthodox comic book featuring the sundial, with the hero’s adventures taking place nearby.

Shapira constructed four more sophisticated sundials in Jerusalem. One stood in Strauss Courtyard (an apartment block and study hall built by philanthropist Samuel Strauss), in the Musrara district; another was affixed to the southern wall of the United Home for the Aged, bordering the Romema neighborhood (near today’s Jerusalem central bus station); the third, resembling an oddly shaped ship’s prow, graced the southern façade of the Etz Haim Talmud Torah school, in the Old City’s Hurva Square; and the fourth still looks out from a wall of the Gra Synagogue (honoring the Vilna Gaon), in the Sha’arei Hesed area.

This last sundial features what became Shapira’s trademark (though it was well known elsewhere): sunlight passing through a small hole at the gnomon’s tip, creating a spotlight that travels over the clockface as the sun moved, using light instead of shade to indicate the exact hour. This element allowed Shapira to build smaller and more accurate sundials.

Moshe Shapira beneath the sundial he built for Etz Haim Talmud Torah in the Old City’s Hurva Square. The woman beside him was probably one of the institution’s benefactors

Moshe Shapira beneath the sundial he built for Etz Haim Talmud Torah in the Old City’s Hurva Square. The woman beside him was probably one of the institution’s benefactorsStopping the Clock

Most interesting of all is the sundial Shapira never built, which made him the center of a political and theological drama that long troubled Jerusalem. Among the many fascinating versions of this legend is that of Shlomo Zalman Sonnenfeld, great-grandson of Rabbi Yosef Haim Sonnenfeld, who famously led Jerusalem’s pre-state ultra-Orthodox community. In 1969, the younger Sonnenfeld visited Shapira on his deathbed in the hospice in Katamon and managed to record the tale. Sonnenfeld included it in his Jerusalem Gems (1987), though told from his own viewpoint and heavily embellished with fictional characters and dates.

Shapira was offered the job, but in the end it was a Muslim clockmaker who installed the sundial on the Temple Mount

Shapira was offered the job, but in the end it was a Muslim clockmaker who installed the sundial on the Temple MountThe story begins during the British Mandate, when Shapira’s reputation as a clockmaker and astronomer had reached well beyond the Jewish community. Bitter controversy was raging among Islamic religious leaders concerning the exact time of noonday prayers on the Temple Mount. One member of the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf (the official body regulating the site) suggested that a neutral expert mount a sundial on the stone arches surrounding the Dome of the Rock. Shapira was offered the job for a tidy sum. Lest this ultra-Orthodox Jew balk at setting foot on the Temple Mount (off limits to all but the high priest on Yom Kippur), the sheikh stressed how much Shapira’s cooperation would contribute to Jewish-Muslim relations – implicitly threatening increased hostility should he refuse.

Frightened, Shapira consulted the elder Rabbi Sonnenfeld. The great sage advised the clockmaker to demand an exorbitant fee and explain that the assignment involved complex religious questions that the rabbis alone could resolve. Shapira did just that, but his “client” was unfazed:

“If it’s the price,” answered the sheikh nonchalantly, approaching an iron chest and taking out a sack full of gold napoleons, which he placed on the table, “Ya sidi Musa – all this is yours…” He indicated the bag. “And if this isn’t enough for you,” he added lightly, “I can provide plenty more.” (Shlomo Zalman Sonnenfeld, The Man on the Wall, vol. 1 [Jerusalem, 1975], p. 363 [Hebrew])

The sheikh’s swift response made Shapira even more nervous. As Sonnenfeld quotes him:

When I realized that money was no object, and that they wouldn’t shrink from even the most unimaginable sums to achieve their goal, I went back to my original point, which was anyway the only pertinent one. In that case, the decision would have to rest with a great rabbinical authority. (ibid.)

Shapira reported to Rabbi Sonnenfeld that he’d been offered an astronomical thirty thousand gold coins – what now? Shocked, the rabbi told him that there might be halakhic room to maneuver, as Jewish law takes financial loss into account. In the end, however, Shapira was resolved:

“I won’t make the sundial by the Mosque of Omar, not even for a million gold napoleons!” (ibid., p. 364)

Beating the clock? Rabbi Yosef Hayim Sonnenfeld considered allowing Shapira to make the clock for the Mosque of Omar. Photo courtesy of the Central Zionist Archives

Into Exile

Having offended the entire Muslim people by declining the job, Shapira knew he’d better disappear ASAP. So the holy scholar fled to Petah Tikva, where he remained – apart from a few secret, fleeting visits to Jerusalem – until his final years.

Jerusalem author Haim Be’er described how his father, a regular at the Zoharei Hama synagogue, traveled to Petah Tikva years later – well after the State of Israel was founded – to urge Shapira to come to Jerusalem and repair the fire damage to the sundial on Jaffa Road:

On his return, [my father] told us that the old clockmaker refused to meet strangers […], and however much they tried to persuade him that the Old City of Jerusalem was now safely in the hands of King Abdullah, and was in any case totally cut off from modern Jerusalem, all their words fell on deaf ears. The old man repeated […] that the Arabs were after him for his refusal to put up a sundial in the courtyard of the Temple Mount. (Haim Be’er, Feathers [Brandeis University Press, 2006], p. 19)

During his long exile in Petach Tikva, Shapira built three sundials on the façade of the Great Synagogue on Hovevei Zion Street. Two were European-style, tracking the hours from January to mid-June and from mid-June through December, respectively. The third showed Jewish seasonal hours, which Shapira called “Jerusalem hours.” This one was probably Shapira’s most sophisticated creation, indicating the earliest time for afternoon prayers, Greenwich noontime, Friday-night candle-lighting time prior to the Sabbath, the shortest day of the year, and more. The accompanying plaque confirmed that though you could take the man out of Jerusalem, you couldn’t take Jerusalem out of the man:

Sundial of “Jerusalem hours” with new “spot” system. Invented by Moshe Shapira, native of Jerusalem (may it speedily be rebuilt), graduate of the Me’a She’arim Yeshiva. Shapira’s three clocks remain a Petah Tikva landmark; Tel Aviv’s Eretz Israel Museum even contains replicas of them in its Sundial Square.

Sundial, one of three adorning Petah Tikva’s Great Synagogue, all made by Shapira during his self-imposed exile

Sundown

Moshe Shapira never married, living alone most of his life in a miserable, sparsely furnished room allocated to him by the Petah Tikva burial society. Rabbi Yitzhak Fishman, the organization’s secretary, was one of the very few who ever saw inside the clockmaker’s home. Fishman described it to theYated Ne’eman daily, paying tribute first to its occupant:

He was an unforgettable figure whose appearance was particularly misleading. Unusually small and wizened, but a giant in wisdom and character […].

His home was basically a storeroom, a sort of American basement, and that’s the saddest part of the story. I went there twice for certain errands, and both times I came out shaken and shocked by its very appearance. It wasn’t that the room was too crowded or too small; it was its emptiness. There was no furniture apart from the barest minimum: a bed, a small chair, and that was it. Nothing else. No fridge, no shower, nothing. His “kitchen,” where he ate his meals, was the Tnuva workers’ cafeterias (which were everywhere sixty years ago), and his shower was in the mikve […].

It was pitiful […]; most of the time he was more isolated than you could even imagine […]. Yet […] you couldn’t say Shapira was bitter or sad. He lived on faith. (R. Gil, “The Sun’s Advantage,” Yated Ne’eman, weekend supplement, Sukkot 5778 [2017], p. 73)

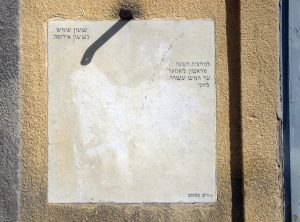

Moshe Shapira, the legendary Jerusalem clockmaker, died in his hometown on 19 Sivan, 1969 and was buried on the Mount of Olives. His headstone says little more than

Here lies a modest and refined man, who built sundials in Jerusalem and Petah Tikva […].

-

Shapira’s tombstone on the Mount of Olives