Oasis in the Desert

Famed for its fertility and rare plants, Jericho was the garden of Judea during the Second Temple period, second only to Jerusalem as an urban center. Hot baths and flowing streams, balsam plantations and the most delicious dates anywhere – small wonder that, according to rabbinic tradition, at least half the priestly class called Jericho home. The jewel in the crown of the archaeological remains of this era are without doubt the Hasmonean and Herodian palace complexes, uncovered along with an adjacent farm in a decade of excavations (1973–83) led by the late Prof. Ehud Netzer.

Netzer attributed four such structures to Hasmonean kings who doubled as high priests: the “buried palace,” dated to the end of the rule of John Hyrcanus (r. 134–104 BCE), son of Simeon, the last of the five Maccabee brothers to govern Judea; the “fortified palace,” erected by John Hyrcanus’ younger son, Alexander Jannaeus (r. 103–76 BCE), on the foundations of its buried predecessor; and the “twin palaces,” apparently built for the two sons of Salome Alexandra and Alexander Jannaeus, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. The rival brothers threw Judea into civil war after their mother’s death, until Hyrcanus enlisted Roman general Pompey and his army to help defeat Aristobulus.

Charles Warren was among the first to excavate the site of the Hasmonean palaces in Jericho. He was actually looking for the biblical city itself and traces of Joshua as well as Jesus

Charles Warren was among the first to excavate the site of the Hasmonean palaces in Jericho. He was actually looking for the biblical city itself and traces of Joshua as well as JesusThe palaces and their artifacts allow us to reconstruct some aspects of the Hasmoneans’ lifestyle and belief system. Through their reception areas and other public spaces, these palatial estates expressed the persona and intentions that their distinguished inhabitants wished to convey to their subjects.

Where’s the Guest Room?

Historians basing their study of the later Hasmonean rulers on historical texts – the most obvious being the writings of Jewish historian Josephus Flavius (c. 37–100 CE) – tend to characterize these leaders as Hellenists. A sad irony accompanies such conclusions: the heirs of the five Hasmonean brothers who fought off the Seleucid Hellenist Empire ostensibly succumbed to the very culture their ancestors abhorred. The second-generation Hasmoneans had Greek-sounding names such as Antigonus and Alexander, hired mercenaries, and called themselves kings despite their disconnection from the royal house of David. One of their womenfolk even reigned over Judea. Seemingly, then, the Hasmoneans embraced Hellenism, with their lifestyle and thinking not substantially different from that of the Egyptian Ptolemies and Syrian Seleucids with whom they alternately fought and negotiated.

Immortalized by Josephus, the later Hasmonean monarchs became important figures in Christian Europe. Woodcut of Salome Alexandra (Shlomzion), the only Hasmonean queen, adapted from Guillaume Rouillé’s 16th-century history of prominent figures from antiquity

Yet the palaces these Jews left behind tell a different story. Josephus and other contemporary sources had their own axes to grind, perhaps preferring to cast past rulers in the mold of those they knew. But the material remains, though partial, reveal how their owners actually lived.

The Hasmoneans were members of the Judean aristocracy of the Second Temple period – the priesthood. Not only did they control the country politically – after the reign of John Hyrcanus, they actually assumed the title of king – they also dominated the high priesthood. Their wealth and majesty, their art and architecture, and even their dinnerware attest to their real culture – Hellenist or Jewish. Their palaces and even the grounds surrounding them indicate their preferred regime as well.

All four of these royal residences are relatively modest. The earliest is also the largest, exceeding two thousand square meters. Attributed to John Hyrcanus, it was apparently destroyed by his son Alexander Jannaeus to make way for his own heavily fortified palace. The latest structures, built for Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, measure only five hundred square meters apiece.

Surprisingly, it seems that the more power the ruler wished to project, the smaller his palace. John Hyrcanus, whose digs were the most majestic, kept the lowest political profile of all the Hasmonean descendants, never referring to himself as king or even ruler on his coins. In contrast, Alexander Jannaeus and Aristobulus II assumed the royal title but lived in a fashion far from kingly. Their “palaces” had no grand reception areas, only bedchambers and small dining rooms typical of any respectable home. In stark contrast, pillared courtyards and magnificent reception halls graced the palaces constructed a few decades later by Herod in Jericho, Masada, Herodium, and elsewhere.

The Hasmonean residences were also designed for privacy, not display. The living quarters lie deep inside, surrounded by outer rooms, with no vestibules, offices, or accommodations for administrative staff or servants. There aren’t even any guest rooms. All these abound in Herod’s palaces, built nearby.

Taking the Plunge

A few examples of Hasmonean décor have been found in the Jericho palaces, including fresco fragments, and a very simple mosaic adorned the farm. Evidently, their owners were aware of Hellenistic and Roman art but used it sparingly. Each palace had its own bathhouse, however, with a water heating system for Greek-style bathing.

The royal precincts really come into their own in their gardens. Eleven swimming pools were dug here, including two measuring eighteen square meters and overlooked by pillared pavilions. An aqueduct provided water from the nearby Perat Stream (Wadi Qelt).

Built over parts of the Hasmonean complex, Herod’s palaces in Jericho incorporated such sophisticated construction techniques as diagonal bricklaying. Though the site has been sadly neglected, this decorative Opus reticulatum is still clearly visible

Swimming pools are a common feature of Hellenist palaces as well as luxurious Roman villas, and Herod later built pools and fountains in his royal complexes. Nonetheless, more swimming pools have been discovered in the Hasmonean palaces in Jericho than anywhere else in the Hellenist world. For the Hasmoneans, pools were evidently the ultimate mark of success, especially in arid locations like Jericho, verging on the desert.

The Hasmonean obsession with water continues elsewhere: ships are carved into the monument built in Modi’in by Simeon the Hasmonean to honor his father Mattathias and the brothers he lost in the struggle for Judean independence, and Alexander Jannaeus’ coins bear an anchor emblem.

No fewer than twelve ritual baths have been excavated in the palaces and water gardens. Four of these mikva’ot were connected to a small, freshwater cistern or reservoir. This “plumbing” allowed the mikveh to be connected with rainwater, in accordance with Jewish law as defined by the Pharisees, the rabbinic Jews of the Second Temple period. Their opponents, the Sadducees, had more stringent requirements regarding the water used for ritual bathing (as did the Dead Sea sect then living in Qumran).

John Hyrcanus’ buried palace also contained a ritual bath with a similar reservoir, reinforcing the Talmud’s identification of the Hasmonean family with the Pharisees. (On the other hand, the Sadducees’ literal interpretation of Scripture was generally stricter than the rabbinic reading and has therefore been associated by scholars with the exacting standards of the priestly class. Indeed, Josephus claims that John Hyrcanus became a Sadducee toward the end of his life [Antiquities, Loeb Classical Library, vol. 5, book 13, sec. 296, p. 375]). Although only part of this edifice has been excavated, archaeologist Ehud Netzer surmised that the adjacent wing housed a mikveh as well.

Only the outer walls of Alexander Jannaeus’ fortified palace have survived, so there’s no way of knowing if it included ritual bath installations. In the eastern of the twin palaces, however, two mikva’ot have been found: one, including a reservoir, next to the palace kitchen, and the other beside the bathhouse. The western twin palace boasted three ritual baths, two of them similarly placed by the kitchen and bathhouse, and the third by the exit to the palace courtyard.

These facilities seem to have been for Hasmonean family use (not for guests), as they were located in the palaces’ inner sanctums. Evidently, Judea’s rulers immersed frequently to remain ritually pure.

The numerous ritual baths in the Hasmonean palace complex attest to the dynasty’s commitment to Jewish law and identity. Mikve adjacent to the Hasmonean burial caves in Jericho

More mikveh installations have been discovered in the public areas of the royal premises. The eastern garden had two (one connected to a reservoir), conveniently located near the storehouses and agricultural installations (oil and wine presses, etc.). Next to the monumental pool complex between the palaces was a small mikveh. The western garden, used mostly for receptions, included a public bathhouse plus three ritual baths, presumably for guests’ convenience. This abundance of mikva’ot indicates that the palace owners also encouraged others, servants included, to observe the laws of ritual purity. Ritual immersion was essentially a matter of etiquette when visiting the Hasmonean royals, especially if dining with them. (Herod’s palaces, too, display a similar preoccupation with ritual purity. In this sense, at least, he was true to his illustrious predecessors and in-laws.)

Made in Judea

Another surprising aspect of the Hasmonean palaces involves the ceramic dishes found there. In sharp contrast to other excavations dating from this period, fancy, imported dinnerware such as red-glazed terra sigillata is completely lacking. So are wine amphoras, perfume juglets, and Hellenist-style mold-cast oil lamps. A generation later, Herod’s palaces and storehouses overflowed with exquisitely painted and crafted ceramics from all around the Mediterranean, but the Hasmoneans appear to have contented themselves with local wares. Everything was simple and undecorated, too, with no glaze or glossy finish, no sign of an incised pattern or border. These dishes could have belonged to anyone.

The absence of imported goods may be connected to the ritual purity issue, but that’s not all. Excavations generally unearth ceramic imports as well as cheap local imitations. But the Hasmoneans avoided even the knockoffs; their patronage of Judean artisans was part of a wider effort to develop an ethnic Jewish identity distinct from that of the all-encompassing Hellenistic world.

Though they welcomed Greek innovations that suited and improved their way of life, from bathhouses to swimming pools and frescoes, the Hasmoneans resisted Hellenistic influence in their everyday material culture. Wherever food and dishes were concerned, these Jews emphasized the barriers dividing them from the heathen Hellenists.

Multiple mikva’ot and lack of foreign tableware – indicating strict observance of ritual purity – are two clear markers of Jewish identity, whether religious or ethnic. The artifacts and layout of the later Hasmonean palaces show their inhabitants to have been sticklers for Jewish law and keen to distance themselves from the impurity and culture of other nations – especially since, as high priests and kings, their lifestyle would have significantly influenced the Jewish character of their kingdom.

Of the People, by the People

This isolationism is evident not only in the archaeological record of Jericho but in written accounts. The author of 1 Maccabees stresses how thoroughly the Hasmonean leaders purged their conquests – the Temple, the city of Gezer, and the Akra fortress – of non-Jewish defilement. In the Temple, for example:

Then said Judas and his brethren, Behold, our enemies are discomfited: let us go up to cleanse and dedicate the sanctuary. […] [They] cleansed the sanctuary, and bare out the defiled stones into an unclean place. (1 Maccabees, ch. 4, vv. 36–43)

And again, in 2 Maccabees:

[Judah] fled into the wilderness, living in the mountains after the manner of beasts, with his company; herbs were their diet all the while, lest they should be partakers of the pollution. (2 Maccabees, ch. 5, v. 27)

Judah and his followers clearly limited their food intake to avoid impurity. Similarly, excavations in the City of David show that Jerusalem’s supply of Rhodian amphoras, used to transport wine all over the Hellenist world, was disrupted from the reign of Jonathan or Simeon until Herod took over the kingdom. This anomaly would suggest a moratorium on imported foreign wine.

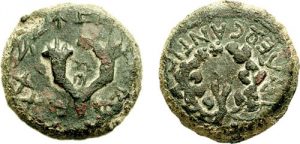

Bronze pruta (penny) issued by John Hyrcanus, marked “High Priest Johanan and Council of the Jews” in ancient Hebrew, and above it the Greek letter alpha

As in Jericho, foreign vessels are glaringly absent from other Hasmonean sites, including Jerusalem’s Upper City and Armenian Quarter, Tell el-Ful, Bet Zur, and Khirbet Qumran. The clampdown on impure foreign imports seems to have been specific to this period, and perhaps even a reform imposed by the Hasmonean rulers.

So while the Hasmoneans might have been somewhat Hellenized, there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary. Their kingdom was certainly overtly Jewish: After conquering the Idumeans and Hittorites, John Hyrcanus and his elder son Judah Aristobulus converted them to Judaism (perhaps consensually, perhaps by force). Furthermore, the Hasmonean rulers reinstated the annual half shekel tax paid to the Temple by all of Judea. (Thousands in the Diaspora also happily chipped in.) And their coins identified each of them as “High Priest and Heber (people) of the Jews,” the latter term indicating that the Hasmoneans saw themselves as representing the nation as a whole, chosen by its will.

Priests and Kings

The Hasmonean dynasty regarded its members as religious leaders as well as political and military figures. “High priest” was the title they prized most. Even Alexander Jannaeus, whose coins proclaimed him King Jonathan in Hebrew, added the title of high priest on the obverse.

The authors of I and 2 Maccabees were clearly Hasmonean sympathizers and stressed the religious aspects of their leadership. Mattathias is compared with the biblical priest Phineas (Pinhas), Judah Maccabee prays before his troops prior to every battle, and Jonathan “judges” the people just like the biblical judges. The Talmudic sages likewise describe a heavenly voice informing John Hyrcanus of his sons’ victory over the Seleucids:

Johanan, the high priest, heard a bat kol issue from within the Holy of Holies, announcing, “The young men who went to wage war against Antioch have been victorious!” (Sota 33a)

Hyrcanus II intervened on behalf of Diaspora Jewry’s religious freedom and privileges, and Julius Caesar recognized him as the ultimate religious authority in resolving a dispute concerning the Jews of Tyre (Josephus, Antiquities, book 14, sec. 195, p. 551).

Bronze coin minted by Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BCE). On one side is an anchor surrounded by the Greek inscription “of King Alexander.” On the other, a three-petalled lily and the name Jehonathan in ancient Hebrew

The Hasmoneans thus aspired to the spiritual leadership not only of their territorial subjects, but of the Diaspora as well. Some claim they did so merely for political gain, but their palaces reveal a complex relationship between Hellenism and Judaism. The buildings, facilities, and dinnerware all bear witness to everyday life under four generations of Hasmonean rule, showing how material culture can reflect beliefs and reinforce a distinct ethnic or religious identity.

Though their opulent palaces, gardens, and fountains projected secular success and power, the Hasmoneans lived by Jewish law. The modesty of their inner sanctums expressed both this commitment and the Jewish identity they painstakingly nurtured among Jews far and wide.