A Dramatic Figure

Despite the freezing December weather, crowds filled the alleyways leading to Mantua’s main square. The grisly climax of Charles V’s historic visit promised to be the best show in town. Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Spain since age nineteen, Charles now held sway over much of the globe thanks to the Spanish maritime discoveries of the Americas and the East Indies. Frederico Gonzaga, the marquis recently promoted to duke in recognition of his many years of service to the crown, had gone out of his way to ensure that his royal guest receive every possible honor, and Charles’ stay in Mantua had exceeded all the emperor’s expectations.

This morning Frederico would receive his reward. Charles had made Mantua the seat of his final judgment on the handsome youth whose oratory had held the masses spellbound just a year earlier. Dressed like a Portuguese noble, confident in the pope’s protection, the fellow was rumored to have death-defying powers. Yet the stake erected during the night left no doubt as to the verdict, and the emperor had no intention of leaving anything to fate. As the prisoner was led to the platform, a hush fell over the throng. His hands and feet were bound, and his mouth muzzled, lest he escape by uttering some incantation, as he was said to have done before.

Who was this comely stranger, and why did his death so urgently concern the Holy Roman Emperor? Why did he attract such attention both in life and after his demise? Even in the Ottoman city of Safed, the angelic maggid who spoke God’s word from the throat of Rabbi Joseph Karo promised the great halakhist:

You’ll merit public martyrdom in the land of Israel in sanctification of My name, accepted as a worthy sacrifice upon My altar … as was Solomon My chosen one, who was named Molkho. (Maggid Meisharim [Vilna, 1880], pp. 92–3 [Hebrew])

Jews in All But Name

Solomon Molkho was born to a converso family in Portugal in 1501, four years after Jewish life there had suddenly ended. The country’s Jews were never driven out – they were too precious a resource for King Manuel I. Instead, though he issued an expulsion edict in 1496, he held onto them through forced conversion. (See “Once Bitten, Twice Shy – Portugese Jewry”.) For the next few decades, the king ignored whatever Jewish practices his New Christian subjects continued in private. Yet he did all he could to integrate conversos into Portuguese society, encouraging his favorite courtiers to marry into their ranks and recruiting them for a wide variety of royal positions.

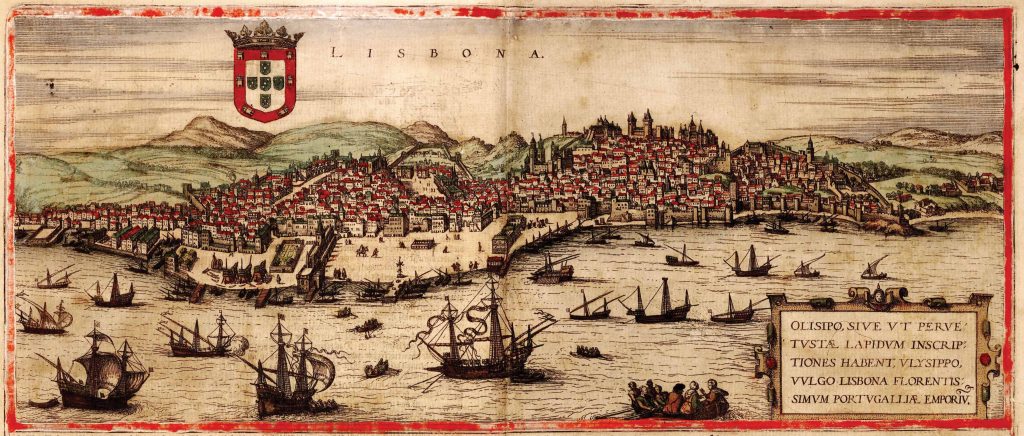

Molkho, whose given name was Diogo Pires, was born during this grace period, but his parents didn’t circumcise him. The family lived not far from Lisbon, then the cosmopolitan capital of a great empire stretching from the African coast all the way to India. The boy grew up against this vibrant cultural and political backdrop.

In 1521, at the tender age of twenty, Pires was made a judge of the appeals court, the highest recourse of Portuguese justice, which traveled with the king wherever he went. Pires’ selection reflected Manuel’s determination to embed his formerly Jewish subjects (many of whom had fled Spain in 1492) in Portuguese society while displacing certain elites, mainly the nobility. Pires’ writ of appointment calls him “Doctor Pires,” so presumably it was his winning combination of higher education and Jewish origins that gained him entry into the royal court.

Alongside his extensive legal knowledge, Pires was well-versed in Jewish law and literature. Unburdened at first by Christian supervision, Portugal’s conversos remained observant Jews behind closed doors, maintaining their customs in detail. One Portuguese refugee noted the painstaking observance of eruv tavshilin, a ceremony making it permissible to cook on a festival for the Sabbath immediately following. This Jew describes his community as learned, with a leader steeped in Jewish mysticism and magic. So not only was basic Judaism still passed down in Portugal in the years after forced conversion, but kabbalistic texts were still studied, and one could acquire a Jewish education both deep and broad. In fact, soon after Pires openly returned to Judaism, his knowledge amazed all who met him. Gedaliah ibn Yihye, the 16th-century Jewish historian, wrote:

… he would lecture in all the Italian and Turkish [Jewish] communities, uttering awesome insights into both the oral and written law – both mystical interpretations and superb and even surprising literal ones. No one had ever heard the like, and no one understood how [he could do so]. (Shalshelet Ha-kabbala [The Chain of Tradition] [Jerusalem, 1962], p. 103 [Hebrew])

Yet Pires remained uncircumcised well into adulthood. He lived between two worlds, not entirely at home in either. Though part of Portugal’s new political and social elite, he secretly delved ever deeper into Jewish mysticism. Yet he was in no hurry to take on the trappings of Judaism, symbolized by circumcision. All of that changed with the arrival in Portugal of David Ha-Reuveni.

Lisbon, view from the sea. Portugal was a world power in the 16th century, controlling shipping in the Far East and imports of gold from Brazil. Growth in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon was so swift that although the entire city was destroyed by an earthquake in 1531, no signs of ruin appear in this etching dating just forty years later

A Fateful Meeting

In 1524, Ha-Reuveni had presented himself in Rome as an ambassador from an independent Jewish kingdom. Far away on the Arabian Peninsula, he claimed, the exiled tribes of Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh lived under their own king. An audience with the pope secured him a letter of recommendation to John III of Portugal (Manuel’s successor), endorsing Ha-Reuveni’s bold plan for a coalition to strike back at the Ottoman armies threatening Europe.

In October 1525, Ha-Reuveni began negotiations with the king and his advisers as to what ships and firepower they could provide for his fictitious country’s planned attack on Mecca and the Ottoman Empire.

Though openly Jewish, Ha-Reuveni commanded universal respect. While there were ostensibly no Jews left in Portugal, the conversos welcomed him with open arms. As a messenger from the long-lost tribes of Israel, he rekindled the community’s messianic longings – and upset the delicate balance of Diogo Pires’ world. Pires records:

In my dreams I saw terrible visions, each different from the next, which struck me with fear … and the thrust of the vision I saw was to command me to become circumcised. (Solomon Molkho, Hayat Kaneh [The Company of Spearsmen] [Amsterdam, 1666], p. 2b [Hebrew])

Pires turned to Ha-Reuveni for help in interpreting these dreams, but the latter was cold and evasive, for his enemies in the royal court were already grumbling about the waves he was making among the conversos. These opponents demanded his expulsion before he completely undermined Portugal’s hard-won new social order. As a result, Ha-Reuveni kept his distance from the New Christians, to Pires’ bewilderment:

I thought to myself: perhaps he’s unwilling to reveal the matter to me while I’m still uncircumcised. So that night, after I left him, I circumcised myself by my own hand, with no one beside me. (ibid.)

Diogo Pires, now known as Solomon Molkho, almost died that night. He recovered, but the damage to Ha-Reuveni was irreversible. The king blamed him for Molkho’s desperate act and for many conversos’ renunciation of Christianity, and he was expelled from Portugal in shame. Molkho fled as well, after further visions informed him that he had a leading role to play in the redemption process. He resurfaced in Italy as “the Messiah son of Ephraim.”

Out of the Closet

Northern Italy in the early 16th century was a hotbed of Jewish immigrants from Germany and France, refugees from Spain and Portugal, and native Italian Jews. A messianic movement developed, led by the enigmatic Asher Lemlin, who predicted the Messiah’s arrival in 1502. A rival circle formed around Jacob ibn Shraga, a Sephardic kabbalist who expected the redeemer in 1512. These messianic and mystic currents drew Molkho to Italy.

Little is known of this chapter of Molkho’s life. Between 1525 and 1528 he gave no sermons, gathered no crowds, and avoided confrontations. He seems to have used these years to solidify the messianic theory he’d begun formulating in Portugal. But he did acquire a group of disciples who accompanied him through the later stages of his brief, tempestuous public career.

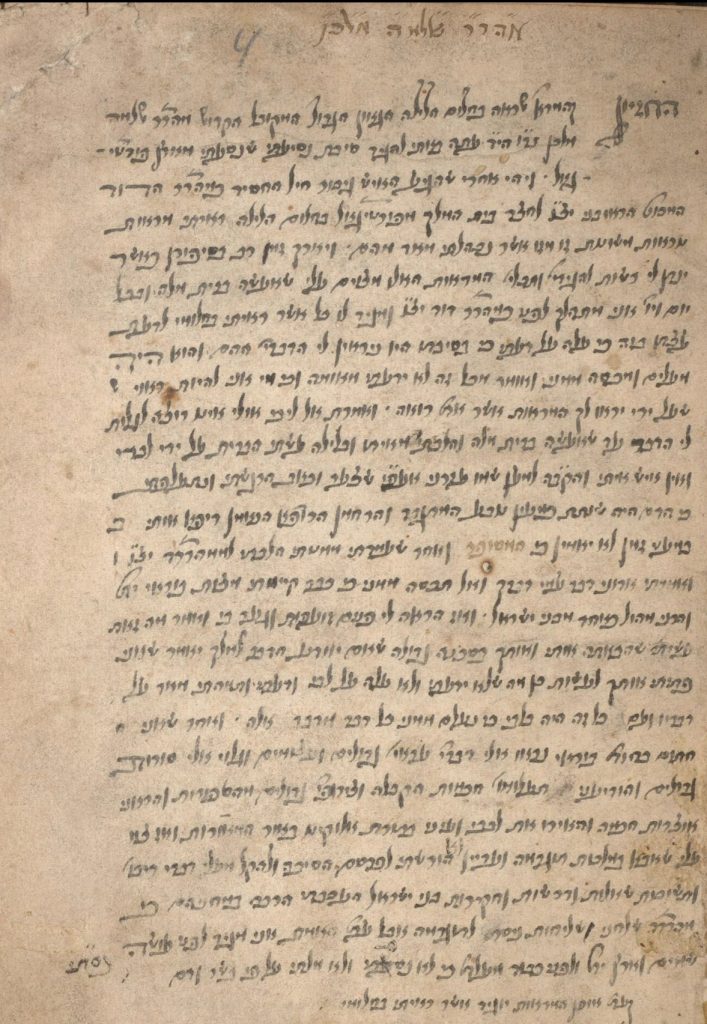

Molkho’s fame extended to Salonika (Thessaloniki), then part of the Ottoman Empire, where a large Jewish community of Spanish and Portuguese refugees eagerly received his novel interpretations and kabbalistic teachings. In 1529, he actually traveled there to preach, supervising the printing of a book of his sermons, subsequently known as Sefer Ha-mefo’ar (The Magnificent Book). In Salonika he met Rabbi Solomon Alkabetz, the kabbalist famed for his liturgical poem Lekha Dodi (Come, My Beloved), still sung in Jewish communities throughout the world to welcome the Sabbath. Molkho may also have come in contact with Rabbi Joseph Karo, author of the definitive halakhic code, the Shulhan Arukh. (Both Alkabetz and Karo later joined the nascent kabbalistic community in Safed, in the land of Israel.)

After a year in Salonika, Molkho returned to Italy a leader. He preached all over, attracting Christians and Jews alike with his calculations of the date of the final redemption. Arriving in Rome, he foresaw a flood of the city and a comet overhead. When he predicted Portugal’s 1531 earthquake as well, his prophetic reputation soared. His advice was sought by such political and religious figures as Pope Clement VII (1523–34) himself. As a result, Molkho was allowed to live openly as a Jew in the papal states and even publish his books.

But Molkho didn’t lack enemies. His bitterest was Sephardic philosopher and physician Jacob Mantino, known for rendering Hebrew and Arabic philosophical and scientific works into Latin. In the 1520s, Mantino had clashed with colleague Menahem Elijah Halfan, who by decade’s end had become a close associate of Molkho’s.

In the summer of 1530, Molkho was living in Venice, but his privileged status kept him outside the ghetto. He was even permitted to appear in public without the infamous “Jewish hat.” Mantino, on the other hand, enjoyed this privilege only briefly. Furthermore, he’d planned to visit Rome in 1530, only to be scared off by Molkho’s warning of imminent flooding (which probably saved his life).

Envious and resentful, Jacob Mantino would stop at nothing to harm his rival. Mantino tried poisoning, accusations of heresy, and finally an appeal to the Inquisition, insisting that Molkho be executed for denying his Christian origins by living as a Jew. Yet his papal patronage always saved him. The Portuguese ambassador rebuffed Mantino as well, scolding him for his devious methods. Eventually Mantino obtained a letter sent by Molkho to Salonika, detailing his life story, including his Christian birth and self-inflicted circumcision. With this proof that his enemy had lied to Pope Clement, Mantino hoped to neutralize the latter’s protection.

Translating the incriminating letter into Latin, Mantino passed it on to the Inquisition. Molkho was sentenced to death – but someone else was accidentally executed instead! Hurrying to inform the pope that his favorite had perished in the flames, the inquisitors were astonished to find their victim standing next to him, large as life. So began the rumors of Molkho’s death-defying gifts.

Although Mantino’s machinations didn’t manage to eliminate Molkho, they disturbed him profoundly, and he returned to Venice a hunted man.

The Ephramite Messiah

Molkho and Ha-Reuveni met again in Venice in the summer of 1532. Their final messianic mission would cost Molkho his life.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had ordered all the German princes and dukes to assemble in preparation for battling the Ottoman Empire, which had conquered Hungary and been driven back from its siege of Vienna just three years earlier. Charles’ greatest concern was that the controversial Protestant Reformation would divide his Christian troops. Many Protestant dukes were already preparing to abandon Charles, and were allegedly negotiating with the sultan before his possible advance into western Europe.

Molkho and Ha-Reuveni arrived in Regensburg in mid-August and were granted an audience with the emperor a few days later. Molkho proffered his help:

They [Molkho and Ha-Reuveni] brought the Jews’ flag with them, and also the shield and sword that he [Molkho] claimed was sanctified by virtue of the Hebrew names of God inscribed upon them. He promises great things against the Turk…. He promises certain victory through his intervention and holy weapons. (quoted in Chava Fraenkel-Goldschmidt, ed., Chronicle of Joseph of Rosheim – Historical Writings [Jerusalem, 1996], p. 183 [Hebrew])

Molkho, then, was offering to put his magical powers at the emperor’s disposal in overcoming the Ottomans, though this Christian leader was still hard at work expelling and persecuting his Jewish subjects, whereas the Ottomans had granted them shelter.

Molkho must have had a hidden agenda. Like many in the 16th century, this Jew considered the messianic era imminent, and he hoped that fomenting conflict between Christianity and Islam would lead to the prophetic war of Gog and Magog. His intention was thus not to help the emperor win, but to drive him into battle. The outcome, as described in the books of Ezekiel and Zechariah, was to be the destruction of the combatant nations and the redemption of Israel. As the self-appointed Messiah son of Ephraim, Molkho was to spark this confrontation, which would reveal the Messiah son of David.

Molkho was well aware of the great personal risk he was taking, for he’d written explicitly that the Ephramite Messiah was destined to die in the war (though he would then be revived by his Davidic counterpart). In stark contrast to many other Jewish messianists, Molkho seems to have been a man of the world. Having moved within the royal circles of a leading European power, and commanding broad academic knowledge, he had a sophisticated grasp of global events. As history unfolded before his eyes, he saw messianic potential. He understood redemption as a historic process, not some sudden miracle, and tried to move history in a messianic direction.

Portrait of Charles V by Peter Paul Rubens, oil on canvas, circa 1600, copied from a painting by Titian in the1550s

Portrait of Charles V by Peter Paul Rubens, oil on canvas, circa 1600, copied from a painting by Titian in the1550sCharles V’s reign was turbulent to say the least. He quarreled with Francis I of France, Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and Henry VIII of England, as well as with the Lutherans and their leader, Martin Luther, whom he eventually outlawed.

From Fact to Fiction

Molkho failed. Unlike Pope Clement, Charles V was unmoved by the self-styled messiah’s claims and sentenced him to death as a recanting Christian. In December 1532 Molkho was burnt at the stake in Mantua. In his final, unmuzzled seconds, he refused to accept Jesus and swore everlasting loyalty to Judaism. After his death, he became a symbol, his flag, coat, and prayer shawl preserved in Prague not long after his execution. Rabbi Joseph Karo yearned to achieve Molkho’s spiritual level, and his Sefer Ha-mefo’ar was republished many times over.

As the 20th century dawned, and with it Jewish nationalism, Molkho was indeed revived – as the hero of plays, novels, and poems. The source of his newfound popularity was twofold. First was his proactive attitude toward redemption; the writers of the new Molkho literature truly believed that human intervention could bring about the messianic era. Second, his desperate attempts were intended – at least as far as these authors were concerned – to make Jews active players once again on the world stage. That, it seemed, was the only road to redemption.