Up Against the Wall

Walking into the first exhibit hall of the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust (at the southern tip of Manhattan Island, just across from the ferry to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island), one can’t help but be struck by the largest piece of Judaica on display: a series of sukka hangings created by Arye Steinberger in Budapest and smuggled across the Austrian border by his granddaughter Piroska Lindenblatt in the confusion of Hungary’s October Revolution. Like the museum as a whole, these decorations reflect not just the culture and way of life preserved by Jewish immigrants in their hearts and minds, but the articles they brought with them, sometimes at great personal risk.

Jack of All Trades

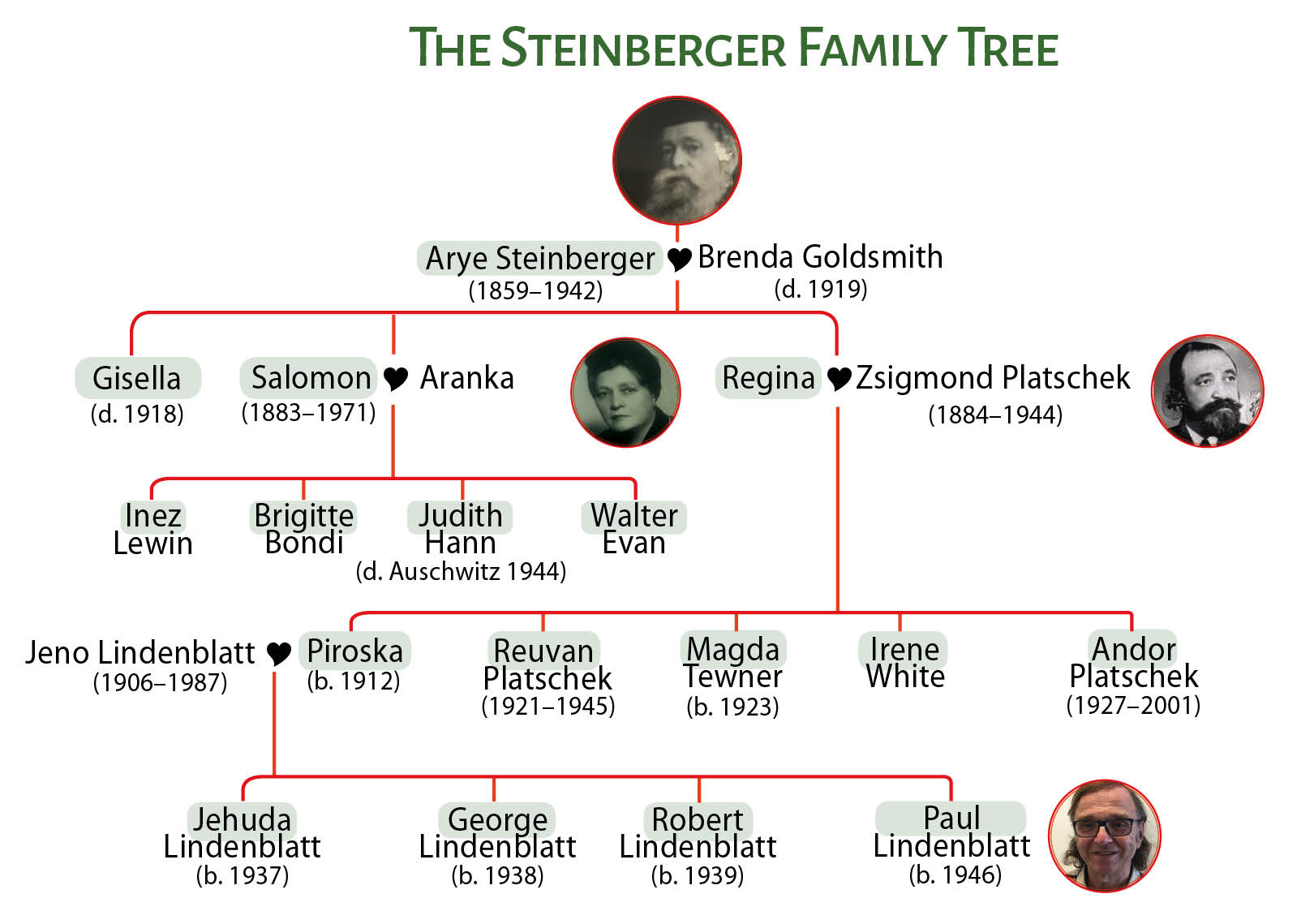

Arye Steinberger was born in the village of Olaszliszka, Hungary, in 1859. A blood libel and a protracted trial of Jews in nearby Tiszaeszlár in 1882 resulted in recurring pogroms in the area, driving Steinberger and his family first to the town of Halas (now Kiskunhalas) – where his children were born – and then to Budapest in 1906.

Wherever his Jewish education came from – the village or the town – it was extensive. He was a shohet well-versed in Jewish law; a teacher steeped in Bible stories and rabbinic legends; and a cantor deeply committed to prayer and never speaking in shul. But Arye was also a talented artist and scribe. His self-taught calligraphy was flawless, and his piety renowned. His love of letters was rooted in Jewish mysticism; he was well-acquainted with the Zohar, including the section dealing with palmistry.

Somewhat incongruously, Steinberger was active in the trade union movement as well. It was actually fairly common for observant Jews to champion workers’ rights in the early 20th century. With fair and prompt pay, a day off, and safe working conditions all mandated by biblical statutes, Jews almost instinctively spearheaded these demands.

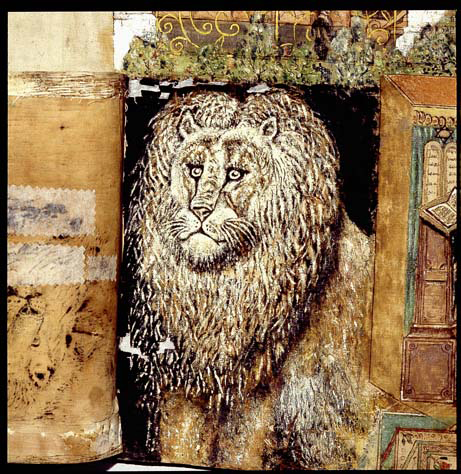

Tall, strong, and fearless as his namesake, the lion, Arye once singlehandedly defended his family from attack on the way home from synagogue, sweeping the assailant off his feet.

Lion’s head – and artist’s emblem – from Arye Steinberger’s sukka hangings

Steinberger had two daughters, Regina and Gisella, and a son, Salomon. The boy received a traditional Jewish education and attended high school in Budapest, then studied for nine years in Pressburg’s talmudic academy. But when Regina wanted to enroll at the local gymnasium, the synagogue committee informed her father that as an employee of the Orthodox Jewish community, he couldn’t send his daughters to high school. So Arye opted for homeschooling, but he devoted much thought to the girls’ future. Seeing Gisella’s short lifeline in her palm, Steinberger became even more pious, hoping to save her. When she died young, just as he’d foreseen, he renounced Kabbala. A kabbalistic amulet he’d written on parchment is still treasured by his great-grandson, Jehuda.

Salomon (a.k.a. Shalabacsi, or Uncle Shala) followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming senior cantor at the Friedberger Anlage synagogue in Frankfurt am Main. (He left Germany for England with his family in 1939.) Widowed early, Arye moved in with Regina and her husband.

The Lion’s Legacy

At sixty-five, Steinberger retired from the slaughterhouse and dedicated himself to the scribal arts, penning ketubbot and gittin (marriage and divorce documents) as well as tefillin and mezuzot. For the family he produced an illuminated Haggada and a scroll of Esther. And to provide for his three granddaughters’ dowries, he wrote three Torah scrolls. One remains in the family, used for bar mitzvas. But his pièce de résistance, years in the making, adorned the Steinbergers’ wooden sukka.

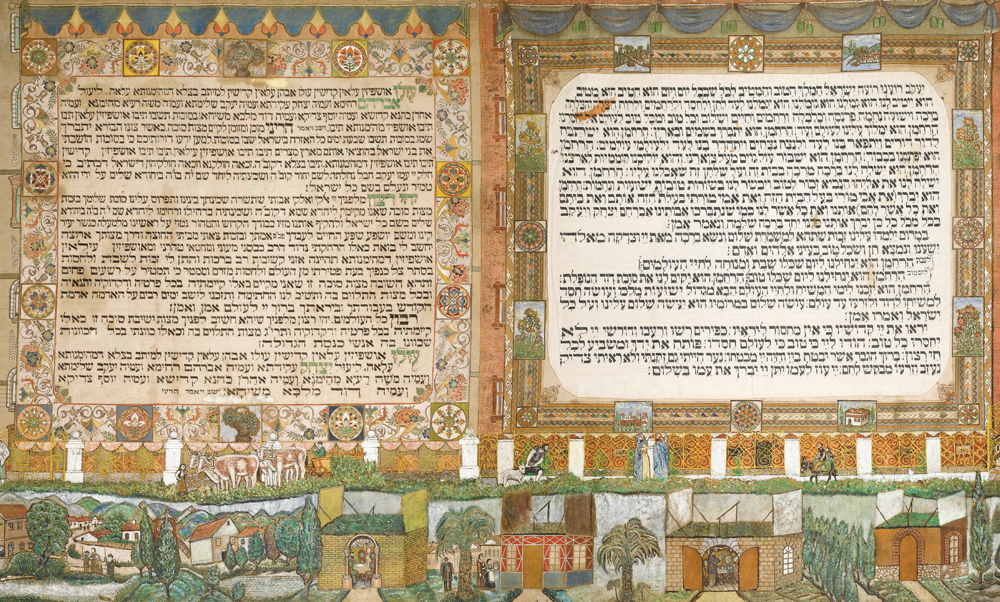

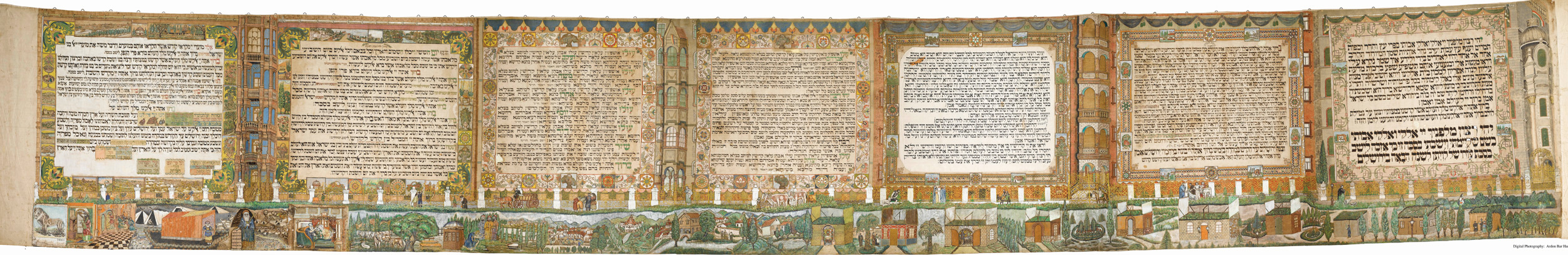

Combining calligraphy and folk art, these four canvas sheets contain every prayer recited within the sukka. The blessing upon entering the structure, grace after meals, the kabbalistic meditation and blessing before shaking the four species, passages from Hallel (the psalms sung on festivals) – all are boldly inscribed within decorative borders.

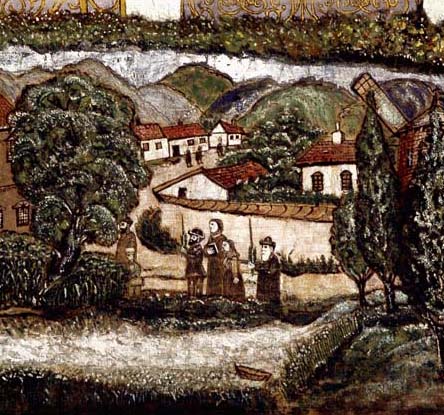

At left: Beneath the elaborate floral border surrounding the kavanot – the meditations for sitting in the sukka and hosting the seven guests, each representing one of God’s attributes – country scenes give way to family portraits and Jewish rituals. Piroska Lindenblatt is painted at left, holding her eldest son Jehuda. Below her, the crowds on the bridge perform the Tashlikh ceremony, figuratively casting their sins into the river

At right: The grace after meals is decorated with a lower panel of sukka booths featuring removable rooves, and more timeless images: a shohet (the artist’s own profession) dragging a reluctant sheep to slaughter; and biblical scenes

Beneath and interspersing these texts are illustrations depicting the life and dreams of Arye Steinberger. Some scenes are from Budapest, others from his native countryside. One panel recreates the elegant gold railings and gates of the Dohány Street synagogue, the first in Pest, built by the Neolog (Reform) community and topped with a Hungarian flag. Dark green cypresses all but wave in a breeze, and palm trees – out of place and drawn from pictures – symbolize the distant land of Israel. Biblical tableaux feature the seven mystical guests welcomed into the sukka each night of the festival: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Aaron, and David.

Among the lush, green, meadows, wooded hills and valleys, bridges, and old, walled towns of Hungary, Steinberger placed his friends and family. At first their faces are blurred, in keeping with the biblical ban on human images; as time passed, however, and it became more important to Steinberger to people the sukka with his nearest and dearest, he consulted his fellow scholars and the rabbis of Budapest, and details were added.

In one pastoral moment, he captured granddaughter Piroska almost knee-deep in grass, holding her firstborn, Jehuda. Arye too “appears” on every panel, represented by a lion. Four generations – the kind of continuity that already then, after the upheaval of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, was no longer taken for granted. Of course, no one knew the worst was yet to come.

Piroska Lindenblatt, the artist’s grand-daughter, with her baby son Jehuda. Detail from the kavanot sukka panel

Steinberger painstakingly mixed colors and inks, using pine sap to fortify them against the seasonal rains to which the sukka stands exposed. In fact, European sukkot were commonly built with wooden roofs that could be raised and lowered to accommodate the weather. These booths too appear on the panels – some open-roofed, others closed. So do Arye’s favorite times of year: the Tashlikh ceremony, in which the Jews of Budapest symbolically cast their sins into the depths of the Danube; the Seder; and Simhat Torah, with Torah scrolls joyously carried out into the street.

Lulav and etrog in hand, worshippers circle the reader’s platform on Sukkot in the synagogue, as featured on the Sukka’s lower panel

Every year, Arye’s masterpiece lined the walls of the family sukka on Regina’s balcony, making it a focal point of Budapest’s shrinking Orthodox community and attracting long lines of eager visitors that snaked out of the apartment and downstairs to the street.

Arye died in 1942, blissfully oblivious to the approach of war. He blessed his daughter and granddaughters and their children on his deathbed, his memory etched indelibly on young and old alike. A year and a half later, the Nazis invaded Hungary.

No Place for Jews

At first Budapest was safer than the countryside, where Jews were quickly and efficiently rounded up and transported to Auschwitz and extermination. Nonetheless, Regina’s son Andor Platschek presciently stored the sukka panels in the cellar of the Dohány Street synagogue for safekeeping.

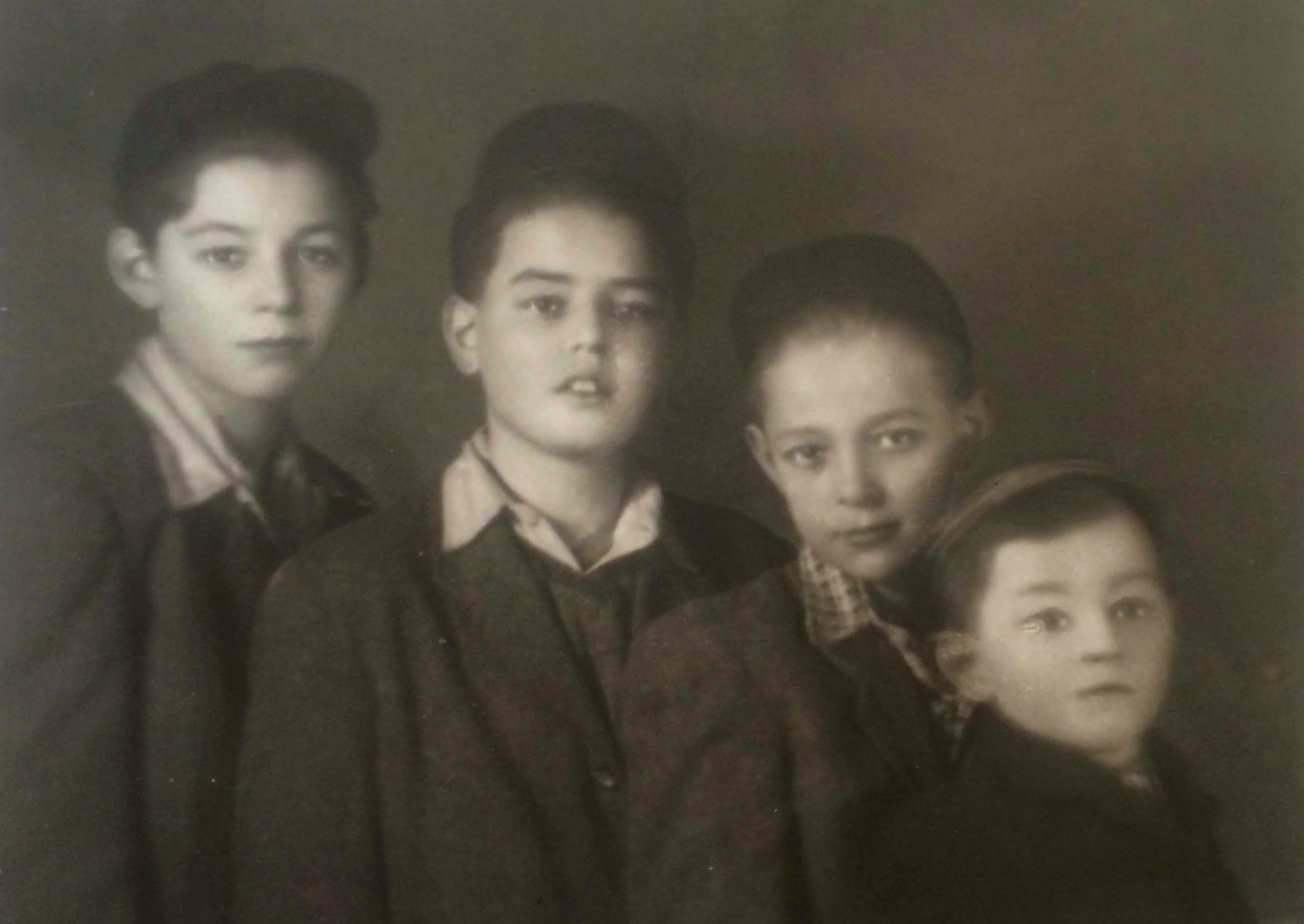

Incredibly, the Lindenblatt brothers have a home movie taken as they and their neighbors emerged from the dark basement of their apartment building, after taking shelter there during one of the first Russian bombardments of Budapest. The yellow star all Hungarian Jews were forced to wear is clearly visible on eldest brother Jehuda’s lapel.

Like many Jews in the city, the family took refuge in the Glass House, a disused glass factory whose Jewish owner had turned it over to the Swiss consul, Carl Lutz. (The building also housed the Mizrahi Zionist Eretz Israel Office, which issued Swiss papers to any Jew it could find.)

There Piroska Lindenblatt survived with her three young sons. Her husband had been sent to a labor camp, her sister Magda to Ravensbruck, her brother Ruvan to Malthausen (where he died not long before its liberation), and her brother-in-law to Auschwitz. Her father, Zsigmond Platschek, insisted on leaving the Glass House to help distribute Swiss papers to Jews facing deportation to Auschwitz. He was pulled off the street and murdered, shot in the neck on the bank of the Danube in the last months of Nazi occupation.

After the war, the remainder of the family regrouped in Budapest. Andor went back to the Dohány synagogue and recovered the sukka panels, which were transferred to Piroska after their mother, Regina, moved into an old age home up the hill in Buda. Piroska named her youngest son – born after the Holocaust – Arye, though in Hungarian they called him Palle (Paul). She’d been very close to his namesake, her grandfather, helping him mix his colors and learning from him how to paint (subsequently applying her artistic abilities to crochet, needlepoint, and embroidery).

The Hungarian Revolution

Most of Piroska’s siblings subsequently dispersed, with Andor leaving for America with sister Irene and her husband, and Magda emigrating to Australia, where Regina joined her in 1958. But Piroska and her husband, Jeno, stayed in Budapest, struggling to feed their family and remain Orthodox. Jeno ran a poultry business, and Piroska sold hand-painted kerchiefs. Any employment meant working on Saturday, and the four boys had school on the Sabbath as well. After a discussion with Piroska, Paul’s teacher made him class monitor on Saturdays, so he wouldn’t have to desecrate the Sabbath by writing. Whenever a substitute taught, however, the boy had to write.

Anti-Semitism was part of life. George, the second brother, was always getting into fights, and Paul remembers a schoolmate cruelly quip, upon learning how frail newborns were left to die on the Spartan hillside, “They should have done that to Lindenblatt too!” And another boy whispering to him from behind, “I’m also a Jew.”

The Lindenblatt brothers in order of age: Jehuda, George, Robert, and Paul Lindenblatt, still in Budapest circa 1950

On October 23, 1956, when Paul was ten, Hungarian nationalists rebelled against the Soviet Union, and life became even more precarious. Armed guards marched in the street beneath the Lindenblatts’ apartment, and a friend called up to him, “No school! No school!” For a week, Hungary was independent. Then the Russian tanks rolled in.

The freedom fighters ran for cover. Six or seven crowded into Piroska’s living room and took up shooting positions at the window. When she tried to stop them, they turned their weapons on her. Paul recalls his eldest brother, twenty-year-old Jehuda, throwing himself in front of his mother and warning the men that she was only trying to save them: if they gave themselves away by shooting, they’d all be killed. The Hungarians realized she was right. The Lindenblatts made them sandwiches and gave them civilian clothes so they’d escape the Russian soldiers’ notice. A few days later, one of the rebels even returned the clothing.

Paul spent most of that week hidden in the cellar, but his brothers had other ideas. In the confusion, the borders with Western Europe were less guarded than usual. Some soldiers sympathized with the Hungarians’ fight for freedom and turned a blind eye to refugees slipping through. There was a chance…

In early November, Jehuda and a friend stole across the border into Austria, and from Vienna they traveled to Israel. In the throes of the Suez crisis, Jehuda volunteered as a paratrooper. Some two weeks later, eighteen-year-old George headed for England. After begging Piroska and Jeno to trust him with their third son, Robert, a family friend sailed with him to America.

Paul’s Story

Left alone with his parents, young Paul was in charge of the family radio. Every day, Radio Free Europe broadcast messages to Hungary, and eventually he heard one in Yiddish from his uncle Andor, telling them the boys were safe. Andor himself was in Vienna, determined to get his last sister out of Hungary and reunite the family.

At the beginning of December, two men arrived at the Lindenblatts’ door in Budapest. They’d come from Andor, they said, and the family should be ready to go at 5 the next morning, when a truck would take them over the border to freedom. Heated debates ensued – whether to go, what to pack – but in the end, the die was cast for leaving.

Piroska knew one thing was coming with them to Vienna: her grandfather’s sukka covering. She carefully divided the large canvases into sections, then used a cut-up raincoat to wrap them in three bundles. Two were large, to be carried by Jeno and herself. The third, much smaller, was entrusted to Paul-Arye, so he’d always treasure it. Also in Paul’s bag was a five-volume Pentateuch in Hebrew and Hungarian (where would they find that in America?).

Early the following morning, in the snowy darkness, the Lindenblatts found five or six trucks parked on their street. The smugglers maximized every trip – the more people, the more profit. Crowded in with other would-be refugees, Paul was shaking, but his mother told him to say the Shema, the biblical verses beginning with “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.” God would protect them, she said.

Not far from the border, the trucks halted. Up ahead, a Russian army truck was stuck in the mud. Once the soldiers had extricated their vehicle, they arrested everyone, confiscated identity papers, and locked their prisoners in a shed. Next morning, they were all loaded back on the trucks and sent home to Budapest. Christmas was coming, though, so it was just a matter of choosing another night, when all the border guards would be too drunk to care who came through. “Don’t worry, Ruskies,” one Hungarian called over his shoulder as the Russians drove away. “Tomorrow we’ll be drinking Coca-Cola!”

Arriving home late that night, Piroska and Jeno found their apartment door padlocked. They woke their neighbors, who claimed to be delighted to see them and handed them the key. The place had been locked “just for safekeeping,” they were told.

Three weeks later, at Christmas, Andor sent another two men. Out came the packages again, but this time the Lindenblatts traveled by train and by day, and Jeno’s parents came to see them off. Upon reaching a certain station near the border, they were to move to the guard’s carriage and wait to be taken across. But it seemed as if the entire train followed them into that car, hoping to leave. The smugglers made themselves scarce.

Piroska wanted to go back, but Jeno was determined. They made their way along the railroad tracks to the signal tower, hoping the signalman would point them in the right direction. Inside the tower was another Jewish family – with money. These Jews bribed the rail worker to guide them across the border to Austria. But could he be trusted?

Lacking money to bargain with, the Lindenblatts agreed to act as guinea pigs. The families chose a code word, which Jeno revealed to the signalman on arrival at what he claimed was the border. The fellow retraced his steps to escort the second family, while Paul and his parents began walking. Snow covered every possible landmark. Paul realized he’d left one of his bags behind, containing two of the five volumes of the Bible. But there was no turning around. Soon the Lindenblatts met other refugees, and they trudged on together.

Suddenly two soldiers confronted them. “We’re taking you back!” the men barked. Jeno lay down in the snow. “You’ll have to carry me. I’m not moving,” he grunted. “We’ve come this far; we’re not going back!” The fugitives scrambled for something with which to bribe their captors. Piroska had what she thought was a spare pair of shoes. Someone else found another pair. Those four shoes were their ticket to Austria.

Now sure of their way, the group staggered forward through the deep snow and bitter cold. Piroska’s shoes were lost in a snowdrift, so she continued barefoot. Then once again, there were people ahead. Someone shoved something round and hard into Paul’s hand. His nerves stretched to the breaking point, he was convinced it was a hand grenade, like the ones the Hungarian freedom fighters had been hurling at the Russians. He looked down and saw it was only an apple. The contingent been met by the Red Cross.

Restoring Past Glory

The Lindenblatts soon found themselves in a DP camp in Austria. Somehow they contacted Andor, and he picked them up by taxi. They boarded in the room next to his in Vienna for a month. While Andor arranged immigration papers for his bride (making her acquaintance had been an additional reason for his trip to Vienna), Jeno sold candy to support his family. Paul enjoyed the leftovers. He also toured Vienna with the carefree young couple. The Lindenblatts feature prominently in Andor’s wedding pictures, since he had no other relatives in Vienna.

Safely in Vienna. Andor Platschek and his bride (seated) celebrate their wedding, with Piroska, Jeno, and Paul Lindenblatt in the background together with members of the bride’s family

The refugee papers came through, and both families set out for America. Traveling via Munich, then Ireland, the Lindenblatts finally arrived in New York. Wherever they went, Arye’s sukka covering never left their sight. The luggage compartment was for suitcases, not priceless family heirlooms.

The family settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, slowly pulling itself back together. George came from England, Jehuda from Israel. Piroska’s sister Magda arrived from Australia with their mother in time for Paul’s bar mitzva, and Regina moved in with the Lindenblatts. Sister Irene was already in Queens. Whenever an important guest came over, Piroska would piece together the sukka covering. You couldn’t really take it in, her daughters-in-law said, but you could appreciate what it meant to her.

Years later, when the family elders were no more and the sukka had been moved to Jehuda’s house, Paul-Arye overheard two men talking in his pharmacy in Boro Park. (“We speak your language,” read the sign outside, and Paul did – Hungarian, Yiddish, and English. He also stocked Yiddish newspapers.) They said a new museum would soon showcase the culture and history of the millions of Jews who’d sailed past the Statue of Liberty and settled in the U.S.

First Paul thought to contribute the home movie from war-torn Budapest. Then he and his brothers began to wonder: they weren’t getting any younger, and would the next generation know what to do with those pieces of canvas, still folded away?

After as much family deliberation as it took to leave Budapest, Arye’s magnificent work of art was loaned to the Museum of Jewish Heritage. And after intensive cleaning, restoration, and preservation, the result is breathtaking. A video also on display records the four brothers’ discussing their great-grandfather, his legacy, and their immigration.

Fulfilling the holiday’s every possible ritual requirement. The Steinberger spread includes grace after meals and welcomes the festival’s seven biblical guests – Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph, and David – most of whom feature

in the miniatures in the

sukka’s lower panels

Thus, one family’s story is no longer limited to the family, and an heirloom is once again enjoyed by all, just as it was every Sukkot in Budapest. Though made to decorate the temporary walls of a sukka, Arye Steinberger’s masterwork has become a permanent part of Jewish history.