The Rock of Destruction

Location: Jerusalem Hills

Near Eshtaol and Zor’a, atop a barren, stony hill along the road to Jerusalem, a lone rock juts out. Here, according to a legend recorded in the early 20th century, a descendant of the mighty Samson breathed his last. This unknown Jew was one of many who answered besieged Jerusalem’s call for stones to fortify the city walls as the Romans closed in. Weighed down by a massive boulder, he marched toward Jerusalem, only to see the city go up in flames from afar. Overcome by grief, the fellow sank beneath the heavy stone and died.

So wrote Israeli professor Ze’ev Vilnai, having heard this tale from the Jews of Har Tuv, near today’s Beth Shemesh. Kahane adopted the story in the early 1950s and set about developing the site. An eternal light was lit there, and a signpost pointed the way for pilgrims from the Jerusalem–Tel Aviv Highway. Dubbed the Rock of Destruction, the spot became extremely popular with Yemenite immigrants living nearby, who prayed there, blew the shofar, and sat on the ground lamenting on fast days. Kahane initiated a custom of replacing the crowns of the Torah scrolls in David’s Tomb on 9 Av – the day on which the Temple burned – with stones taken from beside the fabled rock. This symbolic act, wrote Kahane, expressed “the people’s love for their eternal capital” at the time traditionally marking its destruction (“Tisha Be-Av on Mount Zion,” Ha-zofe Junior, 16 Av 5711/August 18, 1951).

The Cave of the Righteous

Location: Sha’ar Ha-gai

In its first decade, the State of Israel attempted to turn the last stretch of the narrow road leading to Jerusalem into a memorial to the many who gave their lives to secure communications with the capital during the War of Independence. Their heroism was eventually immortalized at a site in Sha’ar Ha-gai, along the Jerusalem Corridor. Kahane conceptually connected this landmark to the Burma Road (created during the war to bypass Arab snipers at Latrun) and the Martyrs’ Forest, planted in 1951 to commemorate the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust.

To link the national narrative of independence with Jewish tradition, Kahane set up a site known as the Cave of the Righteous, exactly twenty-one kilometers from Jerusalem on the road to Tel Aviv. Situated beside the grave of Muslim saint Imam Ali, and not far from where scorched skeletons of armored buses commemorate the victims of attacks on the Jerusalem convoys, the cave featured in a tale penned by Kahane to immortalize their heroic efforts. One convoy, he wrote, escaped its Arab assailants by sheltering here – precisely where “the persecuted righteous ones suffering at the hands of the evil [Hellenist tyrant] Antiochus found refuge” (S. Z. Kahane, Tales from the Wayside 2, p. 17). Though blocked over the years, the cave miraculously reopened to save the modern defenders of Jerusalem. The Religious Affairs Ministry gated the cave entrance and even built a makeshift synagogue beside it.

Though previously marked on local maps, the cave was destroyed a few years ago during roadwork.

Abraham’s Terebinth

Location: Beersheba

Maps of the Holy Land traditionally showed only one point of interest in Israel’s arid southern region: Beersheba, mentioned in Genesis as the place where Abraham planted a terebinth tree. To provide locals with their own pilgrimage site, Kahane created the Terebinth of Abraham on the town’s outskirts, paying tribute to “the father of the nation, who was also the first to plant trees in the land” (“Abraham’s Terebinth,” Ha-zofe Junior, 11 Shevat 5711/January 18, 1951).

In 1949, on 15 Shevat, the New Year for Trees, a procession organized by the Bnei Akiva religious youth movement set out from Tel Aviv’s Great Synagogue carrying a terebinth and other flora. Bused to a site west of Beersheba’s historic center, en route to Kibbutz Hatzerim, the youngsters held a ceremony culminating in the planting of the terebinth, surrounded by twelve olive trees honoring the twelve tribes of Israel. Kahane addressed the thousands gathered for the occasion:

As your feet stand on the physical soil of Beersheba, which has been returned to the people of Israel, and your hands plant an actual terebinth, let your hearts and eyes soar to ancient Beersheba, and to when Abraham stood here and planted a genuine terebinth with his own hands. (Rabbi A. Hen, “On the Terebinth in Beersheba,” Ha-zofe, 10 Adar 5709/ March 11, 1949)

Though Kahane continued the annual tree-planting ceremony in Beersheba, his new tradition failed to catch on. Attendance dwindled, and in the early 1960s the event at Abraham’s Terebinth was cancelled. New neighborhoods later replaced the site.

Mount Sinai

Location: Jebel Musa, Sinai Peninsula

Though Mount Sinai is central to Jewish tradition as the site of the giving of the law, only Christians have tried to locate this legendary mountain. In October 1956, an IDF unit parachuted into the depths of the Sinai Desert at the Mitla Pass, quickly conquering the entire peninsula. Here Byzantine monks had built a monastery where they believed Mount Sinai stood, and Kahane was determined to add the spot – known in Arabic as Jabal Musa, “Mount Moses” – to his list of holy sites.

A month after the Sinai Campaign, Kahane organized a conference in Jerusalem to discuss where the mountain might be and the ramifications of its inclusion within Israel’s borders. Though most of the academics present dismissed the possibility of pinpointing the site, the rabbis preferred to leave the question open, while religious Zionists and right-wing speakers suggested that Jabal Musa’s claims to holiness shouldn’t be rejected out of hand. The whole debate became moot two months later, in January 1957, when the IDF retreated from the Sinai. But just before the withdrawal, Kahane squeezed in a Tu Bi-Shevat event in the area, planting twelve trees – again representing the twelve tribes of Israel – along the dry riverbed of El Arish, the biblical River of Egypt, which constitutes the southern border of the Holy Land.

Grave of Rabbi Gamliel

Location: Yavne

Just prior to the fall of Second Temple Jerusalem, the Sanhedrin relocated to the town of Yavne. Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakai established a Talmudic academy there, where the traditions and precedents of the oral law were studied and preserved. From the Muslim period onward, Jewish travelers referred to the grave of Rabbi Gamliel, head of the Sanhedrin, in Yavne. His mausoleum, they wrote, was described by local Arabs as the tomb of Ali Abu Hurairah, a companion of Muhammad. It was situated on a hill near the ancient remains of the city, bordering the local Muslim cemetery.

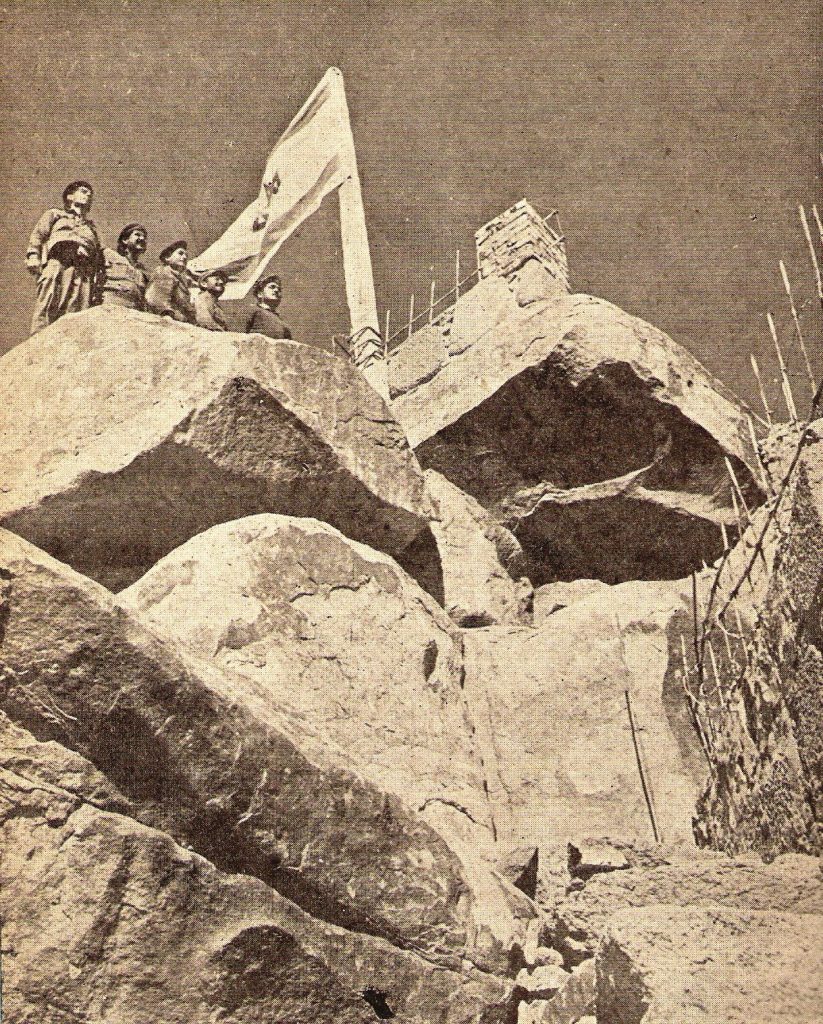

Rabbi Gamliel’s tomb in Yavne, identified and dedicated by new immigrants to the town

Even before Kahane got involved in the tomb, Jewish immigrants living in the abandoned Arab village of Yibne worshipped there. The Ministry of Religious Affairs began reconstruction at the end of the 1950s, adding the grave of Rabbi Gamliel to its pilgrimage routes. The cemetery became a park, and an eye-catching sign was placed at the entrance to the tomb, along with a stand for candles. Curtains embroidered with Rabbi Gamliel’s name were draped over the grave, and a study hall opened onsite, steadily increasing the number of visitors.

The Beacon

Location: Modi’in

Where are the tombs of the early Hasmoneans? Their location was apparently well-known in antiquity, as several sources – including Josephus – place it in the Judean lowlands, by the ancient village of Modi’in. In later generations, however, the tomb’s precise location was lost.

In the early 20th century, the burial grounds of the Maccabees were tentatively identified on a rocky platform northwest of today’s town of Modi’in. A row of trough-shaped graves carved into the rock was known among the Arabic-speaking locals as Kubur el Yahud, “Graves of the Jews.” Tel Aviv’s first educational institution, Herzliya High, brought its students there for Hanukka torch-lighting ceremonies. Gradually, the site became one of the most famous Zionist landmarks. Despite its proximity to the Jordanian border after 1948, the Modi’in area remained the focus of ceremonies, particularly those in which torches lit there were carried by runners to other parts of the country, symbolically spreading the flames of Jewish sovereignty.

After the State of Israel was established, Kahane built a low, altarlike structure known as “The Beacon” (Ha-ur) onsite. Ministry of Religious Affairs officials bore a torch from there to Jerusalem every Hanukka, pausing en route at Sha’ar Ha-gai to meet Israel’s chief rabbi. The torch was subsequently presented to the president of Israel at his home in the city’s Rehavia neighborhood, then carried to Mount Zion, where it kindled a large menora as well as Hanukka lamps saved from communities destroyed in the Holocaust and kept in the Chamber of the Holocaust there.