Sounding the Alarm

Reverberating throughout Elul (the last month of the Jewish year, roughly corresponding to August/September) and climaxing on the High Holy Days, the blast of the shofar has changed little since it was first heard millennia ago. The rudimentary animal horn and the primal sound it produces evoke a raw emotion difficult to pin down. Humble in origin, the shofar can come from a goat, an antelope, or other species, although the standard horn is that of a ram.

In the Bible, the shofar’s uses are varied. When Joshua captured Jericho, seven priests blasted shofars while encircling the city walls, and Gideon’s three hundred men blew ram’s horns to launch a surprise attack on their Midianite oppressors. In a more peaceful vein, a shofar was traditionally sounded every fifty years, at the end of Yom Kippur, to proclaim the economic reset of the Jubilee year, when all slaves went free.

Horn blasts played an important part in ancient battles, serving as signals, warnings, or means of psychological warfare. The biblical Gideon, for example, blew horns to startle his Midianite foe at the outset of his surprise attack.

The shofar was also used in ancient times to announce the onset of the Sabbath. The Talmud (Sukka 53b and Shabbat 35b) describes a series of six shofar blasts blown shortly before Shabbat, alerting people to stop working, prepare food for this holy day, and light candles. One of the more fascinating finds originating on the Temple Mount is a stone from the southwest corner of the Temple platform (then one of the highest points in Jerusalem), engraved: “for the place of trumpeting.” Close to both the Upper City (today’s Jewish Quarter) and the Lower, this spot would have been an ideal place to proclaim the start of the Sabbath – and the daily Temple service.

The Shulhan Arukh (Orah Haim 256), the 16th-century codex compiled in Safed by Rabbi Joseph Karo, reports that this pre-Sabbath tradition no longer existed in its author’s day, although he had heard of it. In Kraków, Karo’s colleague Rabbi Moses Isserles recommended the practice accepted in his community, which had replaced the pre-Sabbath shofar blasts with a town crier. One of the few vestiges of this custom is the sounding of the air-raid siren in Jerusalem and other Israeli cities a few minutes before candle lighting.

“[Belonging] to the place of trumpeting.” This stone, discovered in the southwest corner of the Temple Mount and now on display in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, corroborates the mishnaic description of a specific point on the mount from which shofars or trumpets sounded

Continuing Tradition

We recently visited the Tunisian island of Djerba, possibly the last place in the world where the original practice continues. An anomaly in the modern world, Djerba is a flourishing and even growing traditional Jewish community in a Muslim country. Every Friday, one of its members circulates among the one- and two-story homes in the Hara Kabira neighborhood (Hara is a Berber word of Greek origin meaning “segregated place”) where most Jews live, encouraging shopkeepers to lock up before Shabbat. Much the same thing happened in Jerusalem circa 1900, except that in Djerba they also blow the shofar. The Rosh Hashana sequence of ten shofar blasts (various combinations of tekia, terua, and shevarim notes) is sounded twice – once about ten minutes before candle lighting, to remind people to halt all business, and once when the candles are to be lit. According to the locals, the practice was suspended in other communities for fear of the non-Jews. Living as they do in an essentially all-Jewish district, Djerba’s Jews have no such concerns.

Community rabbi Chaim Biton has been the shofar blower for almost fifty years, having inherited the role from a cousin while still in his teens. We arrived at his house well before candle lighting, determined to record the custom for posterity. One of us took up a listening position in the “town square,” while the other accompanied Biton up to the roof, one of the highest points in town. After frequent glances at his watch, he blew the first series. Looking quite winded, he slowly paced the roof for the next ten minutes, then repeated the sequence. Everyone in Djerba has watches and cell phones, so the Jews all know exactly what the time is, yet they savor this sweet anachronism.

Hanging by a Thread

Most people associate the shofar with Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Even Jews who rarely if ever come to synagogue make an effort to hear the shofar on the High Holy Days. But what happens when Rosh Hashana falls on Shabbat?

The Mishna in tractate Rosh Hashana (4:1–2) discusses whether blowing the shofar desecrates the Sabbath. The rabbis conclude that the shofar should not be blown that day, lest it be carried in public, transgressing a biblical prohibition. In the confines of the Temple, however, the shofar was sounded even on the Sabbath, since a highly regarded rabbinic court was always present to prevent such offenses.

After the Second Temple’s destruction, Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai announced that the seat of the highest religious court of the land – the seventy-member Sanhedrin – would now replace the Temple as a “safe zone” for Sabbath observance. He therefore permitted the shofar to be blown on Shabbat in Yavneh, the Sanhedrin’s new abode.

Early medieval commentators discussed whether such leniency could be extended to any city with a religious court numbering at least twenty-three. Could a regular rabbinic court of three sages count as well? In Fez, the renowned Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (1013–1103) said yes. As a result, the Moroccan Jews of his day evidently blew the shofar even when Rosh Hashana coincided with Shabbat.

Likewise, fragments of early medieval liturgical poetry from the Cairo Geniza depict the blowing of the shofar in such a case:

O King who warned the court / to blow in the courthouse / when the New Year falls on the Sabbath,

O King who strengthened them with the teaching / that the shofar should be tied to a post / when the New Year falls on the Sabbath,

O King who made it clear to the congregation / not to blow unless the protocol-makers were present / when the New Year falls on the Sabbath,

O King who ordered aloud that none should hold [the shofar] in his hand / but should close his lips upon it where it was bound / when the New Year falls on the Sabbath

The changes described here – tying the shofar to a pole and blowing it without touching it – were to underscore the unique circumstances of Rosh Hashana on Shabbat, so the shofar could be blown without worrying how it got to the synagogue.

We found further evidence of this practice in the basement repository of the Sephardic community in Sofia, Bulgaria. Three very old, black horns had been placed there, a long thread wound around each. Might these threads have bound the shofar to a post, so it could be blown when Rosh Hashana fell on Shabbat?

Was this shofar blown on the Sabbath? A black shofar tied with a leather thong, discovered in the basement of the Sephardic synagogue in Sofia, Bulgaria

In 1881, Rosh Hashana coincided with the Sabbath. In Jerusalem, a relatively recent arrival from Hungary, Rabbi Akiva Yosef Schlesinger (see “A Man unto Himself”), decided to blow the shofar in accordance with Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai’s ruling for Yavneh. Schlesinger assembled twenty-three learned rabbis, so he would be blowing before a prestigious religious court. Rabbi Yehiel Michel Tukachinsky, then a ten-year-old, vividly remembered the hullabaloo created by Schlesinger’s plan. One by one, his twenty-three court judges disappeared, leaving him with barely a minyan. Yet Rabbi Shmuel Salant, chief rabbi of Jerusalem, refused to ban the event, though he also didn’t sanction it. Rabbi Tukachinsky writes:

In the summer of 1904, when I brought the coming year’s calendar of laws and customs in the Holy Land to the great Rabbi Eliyahu Rabinowitz Teomim [1843–1905] for approval, he sighed and said: “It’s a shame that this coming year Rosh Hashana falls on Shabbat, as I may never again fulfill the biblical command to hear the shofar.” (He was feeling unwell and indeed passed away on 3 Adar I, 5665 [1905].) Then the rabbi added: “If Rabbi Akiva Yosef [Schlesinger] were to blow the shofar this coming Rosh Hashana, I would go stand behind the wall to hear its sound.” (Rabbi Yehiel Michel Tukachinsky, Ir Ha-kodesh Ve-ha-mikdash [The Holy City and the Temple], vol. 3, p. 284 [Hebrew])

Which Horn Is Best?

To appreciate exotic shofars (or shofarot in Hebrew), one has to know a bit about the different types of animal horns. A horn is a protrusion of bone covered with a layer of keratin (the protein our hair and nails are made of). Horns are not to be confused with antlers, which are made of bone (covered with a velvety “skin” during the growth period), are shed annually, and may not be used as a shofar. A kosher shofar is made from a horn cut from a dead animal. The keratin sheath is separated from the bony inner horn. The resulting hollow shell is what actually serves as the shofar. The wide, open end of the horn was originally attached to the animal’s skull; the narrow end, which is solid, will have a cavity drilled into it to become the mouthpiece. Most shofars undergo a heat treatment allowing the solid part to be straightened for drilling. Otherwise the drill could easily hit the curved part of the horn, puncture it, and make the shofar invalid.

Since any horned animal is kosher, any animal horn may be used for a shofar – except a cow’s. So the antelope and gazelle can provide valid shofars, as can the ibex. Like a medieval trumpet, the horn of an African gemsbok produces beautiful, deep bass sounds. Acoustics notwithstanding, ram’s horns are highly preferable, since Abraham sacrificed a ram instead of his son in the biblical story of the Binding of Isaac.

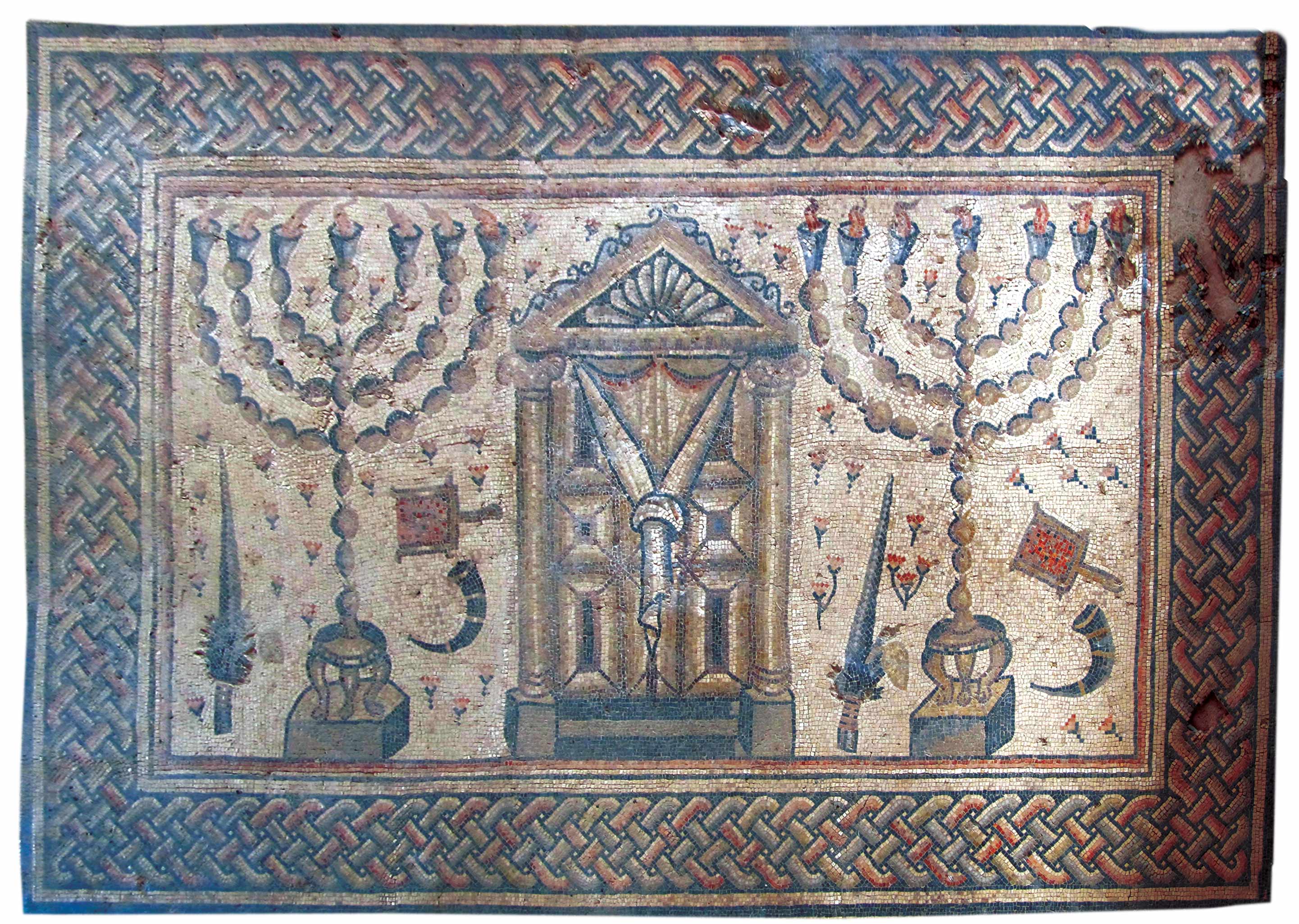

Although there is little evidence as to what kind of horn was used in antiquity, ancient coins and mosaics give us a clue. The crude, tiny images appearing on coins suggest a short, curved horn such as that of a ram, but mosaic representations, being much bigger, are probably a better indication. In 1921 a mosaic floor was uncovered just south of Tiberias, in the remains of a small synagogue dating from the third to fifth centuries CE, when the Sanhedrin convened in the city. (Known today as the Severus Synagogue, this house of worship was probably the main one in the area and may well have been frequented by the period’s foremost scholars.) The shofar that appears together with other ritual items in one of the mosaic’s main panels actually resembles a bull’s horn, which according to nearly all opinions is unacceptable as a shofar. Presumably, then, the mosaic depicts a curved ram’s horn.

Shofars figure prominently in ancient synagogue mosaics. In this fragment from Hamat Tiberias, found in 1921 and dated to the third or fourth century, two shofars appear among the four species, seven-branched menoras, and coal pans surrounding what may represent the Temple façade

The first coins produced by Jews were authorized by the Persian Empire in Yahud – the Persian name for the province of Judea – in about the sixth century BCE. They often featured a shofar, among other symbols

Discovered in Jericho in 1936, the sixth- or seventh-century Shalom al Yisrael synagogue also features a mosaic floor. Among its design elements are a holy ark, a menora, a palm branch (or lulav), and a shofar, also clearly a curved ram’s horn.

Similar evidence from synagogue mosaics in Beth She’an, Tzippori, and Ashkelon – all dating from the same period – confirm this conclusion, as does a late-fifth-century ritual bath at Kibbutz Hulda.

But the conventional ram’s horn has occasionally been exchanged for something else, and not always intentionally.

Ram, Goat, or Antelope?

A surprising anecdote was recounted in a letter by Rabbi Yom Tov Lipmann Mulhausen (died ca. 1421) and quoted in 1869 by Abraham Berliner in the Zionist daily Ha-levanon (35, 26 Elul 5629).

A colleague of Rabbi Mulhausen’s, Reb Zamlin Hakohen, visited a nearby workshop where a non-Jewish father and son made shofars used throughout Germany. There he stumbled upon the terrible secret that all these shofars were made from goat horns! Even when a Jew handed them a ram’s horn to be fashioned into a shofar, they substituted a goat horn. The reason was very simple – goats’ horns are straighter than rams’, and the mouthpiece can thus be drilled right through, with no heating or straightening. Mulhausen bemoans the shocking fact that for forty years, all the Jews of Germany had been blowing goat-horn shofars! (Several years ago, goat horns were also used in Lubavitch shofar -making demonstrations in the United States – hopefully by mistake.)

Mulhausen arranged for Reb Zamlin to teach Jews the trade, and for two years they manufactured ram’s horn shofars. These were apparently dire times, which Mulhausen attributed to the “curse of Rabbi Isaac” (Rosh Hashana 16b), according to which tragedy strikes whenever the shofar is not blown – or blown improperly. Mulhausen attempted to put things right by publicly cursing anyone making or using a shofar produced from anything other than a ram’s horn. This curse applied whenever a ram’s horn was available, even if it was smaller or produced a poorer sound than other kosher horns.

Mulhausen had other complaints. He pronounced all the Torah scrolls of his generation defective, contending that the scribes didn’t know how to spell or space the text. It’s hard to believe that among Jews as organized as the Germans, both the shofars and the Torah scrolls were invalid, so Mulhausen’s quibbles should probably be taken with a grain of salt. But the use of goats’ horns instead of rams’ has certainly not been limited to his time.

Sound of the Kudu

The best-known example of the sounding of a non-ram’s-horn shofar is also the most puzzling. Yemenite Jewry generally follows the rulings of Maimonides, who clearly states in his Mishneh Torah (Laws of the Shofar 1:1) that the commandment of blowing the shofar requires a ram’s horn. Yet the “Yemenite shofar” is made from the long, twisted horns of the greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), a kind of antelope.

Rabbi Jacob Sapir of Jerusalem recounted in his book Even Sapir (1990, p. 165) how he spent Rosh Hashana 5620 (1859) in the Yemenite town of Mocha, and mentioned his difficulty blowing the local shofar. He described it as the meter-long, twisted horn of an ibex, which produced a loud, frightening blast. Ibex horns are curved, however, not twisted, so he probably meant the horn of the kudu.

Although the late Rabbi Joseph Kapah (1917–2000, Yemen and Jerusalem) asserted that most Yemenite Jews did use rams’ horns, he admitted that the kudu horn was also blown, particularly in the city of Sana’a. When challenged, those using the kudu shofar claimed an ancient tradition among Yemenite Jews, in accordance with the basic law that all horns may serve as shofars, as long as they don’t come from a cow.

When is a horn not a shofar?

Whether it’s used exclusively in the period leading up to Rosh Hashana or for other purposes as well, whether it’s blown to mark the Sabbath or in spite of it, and whether it sounds the deep notes of the kudu or antelope or the higher, nasal pitch of the ram’s horn, the shofar continues to reverberate in the Jewish consciousness. There’s a growing tendency to embrace a variety of horns – some easier to blow, some harder – sounded with different degrees of virtuosity. But however and wherever it’s blown, the shofar echoes the Jewish people’s long and varied wanderings.

![“[Belonging] to the place of trumpeting.” This stone, discovered in the southwest corner of the Temple Mount and now on display in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, corroborates the mishnaic description of a specific point on the mount from which shofars or trumpets sounded](https://segulamag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/vflpl4188i2inawrgfvi.jpg)