Baby Air Force

Twenty-five years have passed since the Israeli Air Force Museum opened in the blazing sun over the Hatzerim air base, not far from Beersheba. Hundreds of models of retired warplanes are arrayed there, alongside enemy aircraft knocked out of the sky by Israeli soldiers. Bold-lettered signs proudly proclaim such riddles as “Mirage 3, Shahak 159, 13 downed”; anti-aircraft guns and an outstanding exhibition on the work of the army’s Airborne Rescue and Evacuation Unit round out the display.

Wandering among the exhibits takes you back to the beginning of the air force, and the crazy adventures involved in acquiring planes to defend the beleaguered State of Israel in the throes of the War of Independence. The main hero of the story was Emanuel Zurr, who masterminded an airplane-running operation from Britain in 1948.

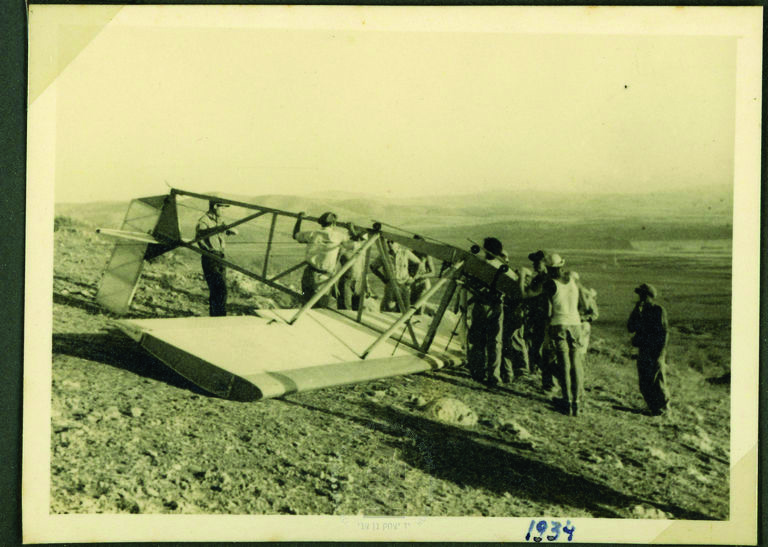

Members of the Israel Flight Club with an overturned glider at Kfar Ha-yeladim, near Afula, 1934

Galician flight instructor Emanuel Zuckerberg arrived in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s. Unable to find employment, he worked for a few years as a mechanical engineer. Then he took a job at Aviron, a flight company owned (like nearly all going concerns in Palestine’s Jewish economy) by the Histadrut national trade union. Aside from serving as the firm’s engineer, and foreman, he flew passenger trips to and from Europe, Syria, and Egypt and built connections through the company’s office in Paris. Zuckerberg was also the country’s first (and only) licensed flight instructor, training pilots for the Hagana (the Jewish home guard), then for the Palmah, its full-time branch.

Emanuel Zurr (Zuckerberg) in uniform as head pilot and flight instructor of Aviron, 1938

Immediately after approving the partition of Palestine in November 1947, the United Nations imposed an arms embargo throughout the Middle East. A prestate air force barely existed, and the prospect of fighting Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon with just ten single-engine Piper planes was unthinkable. David Ben-Gurion, soon to be prime minister, called Zuckerberg. After insisting that the flight coach exchange his Diaspora-style name for the more Israeli-sounding Zurr (literally, “rock”), Ben-Gurion appointed him national aeronautical acquisitions emissary to Europe.

The Bristol Beaufighter was one of the most effective bombers manufactured in Britain in World War II. Almost six thousand took to the skies during the war, fighting on nearly all fronts for the British, Australian, and American air forces. British Beaufighter

Over the next few months, using his extensive professional contacts, Zurr cobbled together a small force of Czech light aircraft from obscure global locations, but it was nowhere near enough. War broke out with the declaration of the State of Israel in May 1948, and the Egyptians started bombing Jewish villages in the Negev from the air. Without help from heaven, in both senses of the word, the young state was in peril.

The Bristol Beaufighters

In June 1948, word reached Zurr that a London aviation aficionado had purchased twelve World War II Bristol Beaufighter bombers as scrap from the British Royal Air Force. The Beaufighter was an excellent double-engine aircraft with four guns and a worthy record.

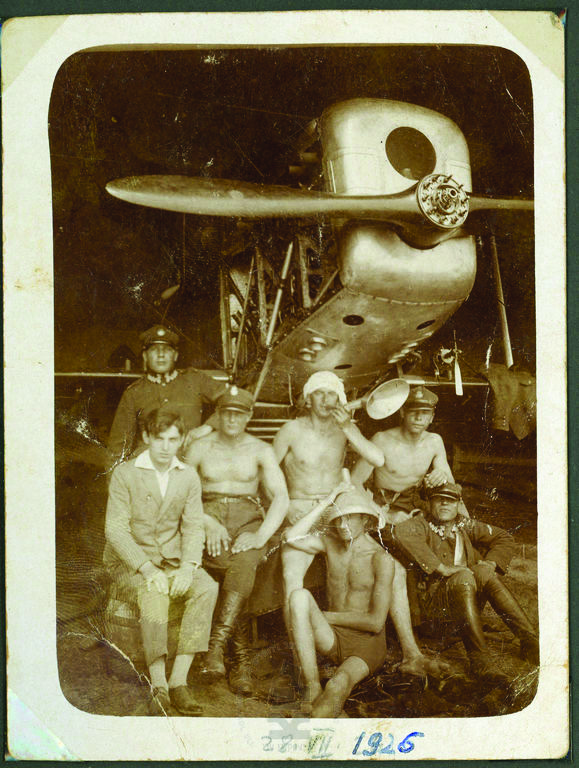

Early ambitions. Zuckerberg (seated at left) at age fifteen with Polish pilots and other flight staff in Stanislav, Poland, July 1926

Emanuel Zurr (left) and graduates of Mandate Palestine’s first pilots’ course pose in front of an RWD-8 plane owned by Aviron at the Afikim airfield, 1939

Already known to Scotland Yard as a plane smuggler, Zurr couldn’t risk entering the United Kingdom, so he sent a British acquaintance to check out the merchandise. His protégé reported that the planes were in bad shape, but the London collector – an ex-RAF general specializing in aircraft repairs – offered to sell them for only fifteen hundred pounds sterling apiece, including refurbishment.

Zurr had to view the planes himself before deciding to buy, so he flew to France, hired a light aircraft designed for short distances and capable of slipping in under British radar, and landed secretly outside London. Devastated by the planes’ condition, he was about to fly straight home, but the desperate seller slashed his price and swore he’d have the Beaufighters up and running in two to three weeks.

After much persuasion, Zurr agreed to acquire only half the aircraft – those he considered salvageable. But who would fly them? And how to sneak them out of England without the entire Royal Air Force in hot pursuit?

New Zealand Dreaming

Flying to Aviron’s French office, far from the prying eyes of British intelligence, Zurr sought a solution. A chance conversation with a young woman from New Zealand, who’d fallen in love with one of his pilots and come to see when he’d be arriving in Paris, pointed in a promising direction. She told Zurr she’d always dreamed of starring in a movie about New Zealand’s role in World War II. A crazy idea began germinating in Zurr’s brain, one of the most brilliant, daring smuggling schemes ever.

He would set up a fictitious British film company producing a swashbuckling tribute to New Zealand’s pilots and their battles against the Japanese. The studio would insist on shooting in Scotland, whose landscapes resemble the green hills of New Zealand, and the Bristol Beaufighters would be filmed taking off from England. Once airborne, of course, they’d head for Israel. (A remarkably similar ruse rescued six U.S. diplomats from Tehran during the 1979–81 Iran hostage crisis, as dramatized in the Oscar-winning 2012 film Argo.)

Zurr with a plane owned by Cinda, a French aviation firm that employed him in Paris, 1931

Naturally, the plan required pilots, so Zurr roped in South African colleague Terence Farnfield, an ace fighter in the British Royal Air Force who had already flown a few of Zurr’s purchases to Israel, and whose wife happened to be Jewish. Farnfield put together the “Air Pilot Film Company” and started interviewing pilots and other cast members for a blockbuster showing the New Zealand pilots in action. Extensive research was undertaken and a script produced, full of heroic scenes and glorious aerial shots. The star-struck New Zealander was cast as the pilot-hero’s beloved, having no clue of the secret “plot behind the plot.”

Hectic weeks of auditions and interviews were spent mostly determining which pilots could be trusted – and paid handsomely – to smuggle out the planes. Then Zurr discovered that the ex-general had managed to get only five into flight condition, so only five pilots were selected.

Emanuel Zurr (left) and graduates of Mandate Palestine’s first pilots’ course pose in front of an RWD-8 plane owned by Aviron at the Afikim airfield, 1939

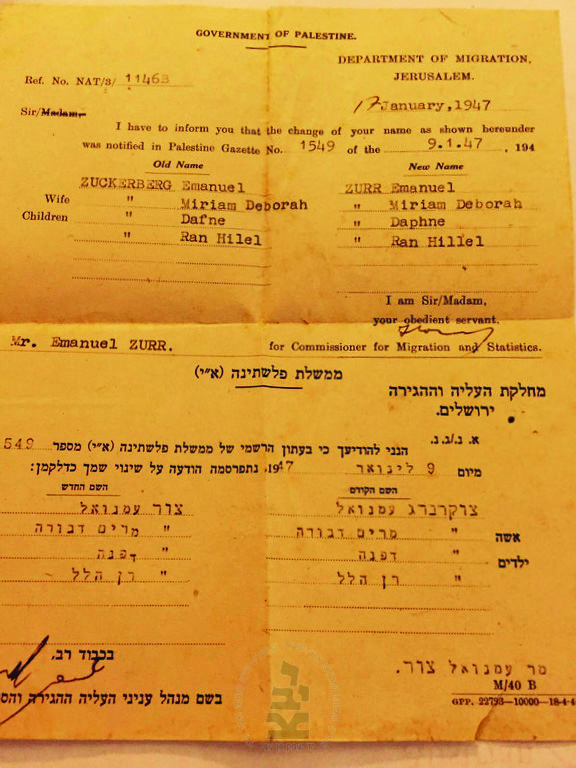

As this certificate of the Mandate immigration department testifies, Zuckerberg changed his name to Zurr on January 9, 1947

Actors, make-up artists, cameramen, lighting technicians, extras, and a host of others scurried around a vast set, all but a few convinced that they were really making a movie. Scotland Yard did in fact start sniffing around, so a good four days were devoted to actual filming. Busloads of cast and crew left London every morning for an airfield on the outskirts of the metropolis, where the Beaufighters took off and landed in full coordination with the British flight authorities, amid cries of “Lights! Camera! Action!”

On the third day of shooting, tragedy struck: a plane went into a spin, malfunctioned, and crashed, killing its pilot. Everyone thought the project over, but Zurr and his cohorts insisted that the show must go on. The New Zealand airmen deserved a fitting memorial, said the producers – come what may.

In Flight

So production proceeded, and on Thursday, August 2, 1948, four planes took off, ostensibly for Scotland, where filming was to continue. Tens of weeping extras waved their handkerchiefs as their “heroes” departed for the “front.” The cameras whirred, the engines growled, and the aircraft disappeared into the clouds. No one expected them back in England; they were presumed to be landing somewhere in the Scottish Highlands. That enabled the pilots to clear British airspace and head wherever they pleased. Four and a half hours later, they landed in Corsica for their first refueling. The local inspectors were bribed, and the fighters flew on unimpeded, stopping next in Yugoslavia.

On August 4, the squadron landed to much applause at the Ekron airfield, today the Tel Nof air force base. A team of painters descended on the four weary planes, and the next day they were already flying in the service of the Israel Air Force (IAF), doing their part for the War of Independence. Though battered, the Beaufighters made a real impact in dogfights with the Egyptian Air Force, until they finally fell apart after just four months. One of them didn’t last even that long, crashing over the Ashdod sand dunes. But its sooty remains are on display at the IAF Museum.

All that remains of the Israeli Beaufighter plane that crashed in the Ashdod sand dunes in 1948, incorporated into a monument at the Israeli Air Force Museum

Only four days later, Ben-Gurion sent Zurr back to Europe to scout out more planes. All together he purchased eighteen in four months, mostly by means almost as hazardous as the Beaufighter caper. A grateful prime minister made him the first director of Lod Airport, later named after Ben-Gurion himself.

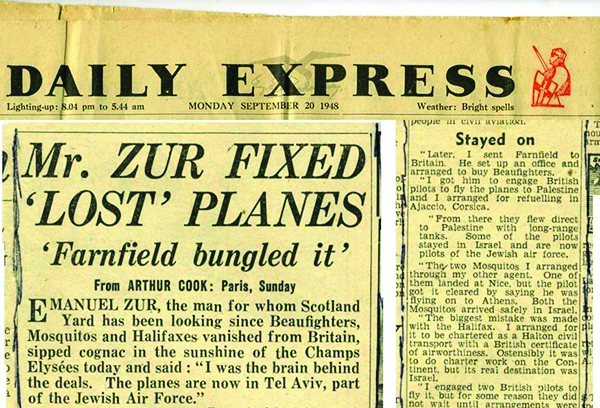

Not all Zurr’s purchases arrived as smoothly as the Beaufighters, as this Daily Mail headline from September 1948 attests

Zurr eventually opened his own flight company, wrote Israel’s flight regulation manual, and helped develop the compact Westwind executive jet made by Israel Aircraft Industries. He died in 1991, but the legend of the amazing pilot who moved heaven and earth to save the young State of Israel lives on.