David and Jerusalem

A political leader named David transports a national relic through the Judean Hills to Jerusalem, placing it at the crest of a hill as a “spiritual center” for the new capital. But when? In the 11th century BCE – or the 20th CE?

Two strikingly similar stories, separated by nearly three thousand years, describe the establishment of a Jewish capital in Jerusalem. The first, of course, is the story of King David and the Ark of the Covenant; the second, lesser-known episode involves Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and the bones of Theodor Herzl, which were brought from Vienna to Jerusalem for re-interment in the summer of 1949.

There are remarkable parallels not only between the events, but in the motivations behind them. While David’s goals in turning the centrally located Jebus into a national religious center – the City of David – are well known, Ben-Gurion’s motives are less familiar. But they could just as easily have been voiced by King David. When Minister of Police Bechor Shitrit suggested burying Herzl in Haifa (as some thought was his request), Interior Minister Yitzhak Gruenbaum replied:

I think that specifically now, when our intention is to strengthen Jerusalem and make it into a spiritual center … the most appropriate place for Herzl’s tomb is Jerusalem. (Israel government protocols, May 10, 1949, p. 26, Israel State Archives [Heb])

It is no secret that the Zionist leadership harbored reservations about the role of Jerusalem in the state-to-be, as had Herzl himself before actually setting foot in the city. His visit induced mixed emotions and resulted in a new vision for Jerusalem, which he set out in his novel Altneuland. Ben-Gurion did not visit the city until two years after his arrival in Palestine, and others waited far longer.

A Secular Shrine

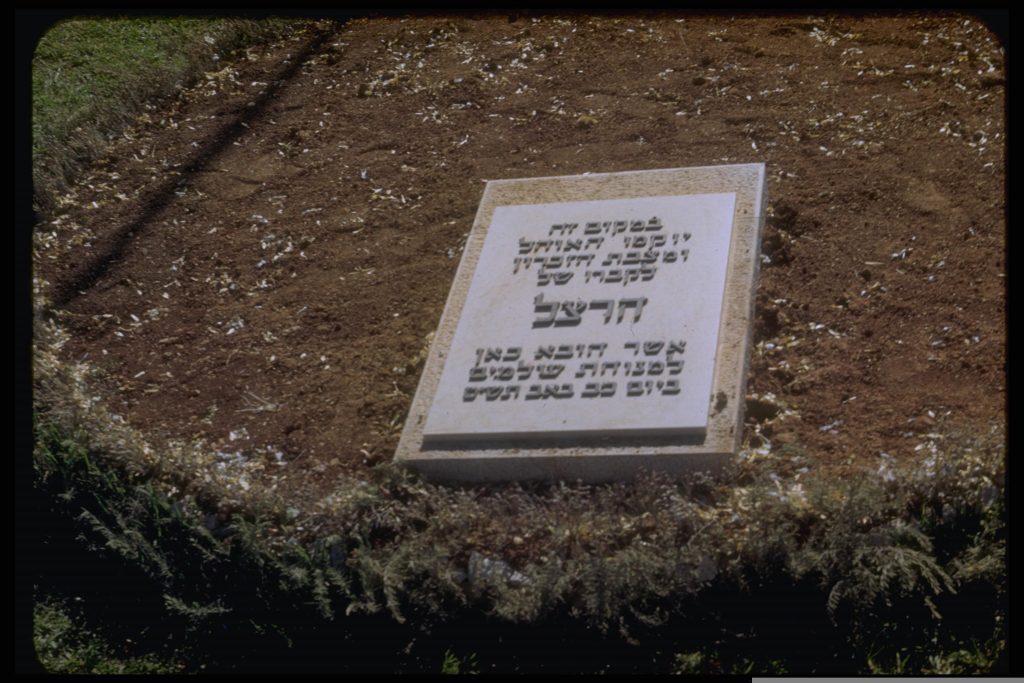

Herzl is buried atop the hill that bears his name. Heads of state, Zionist leaders and thousands of fallen soldiers are buried in the military cemetery on the hillside. Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum, occupies the western slope. The plaza in front of the tomb hosts the annual Independence Day ceremony, while the Memorial Day service preceding it is held nearby, at the burial plot of the nation’s leaders. While Ben-Gurion was originally unenthusiastic regarding the choice of Mount Herzl, a hill then on the outskirts of western Jerusalem and far from the city’s inaccessible historical center, the site rapidly became a national shrine. Its location on the opposite side of Jerusalem (and of the Jordanian border for the first years of the state) from the ancient holy sites may even have made it more desirable as a center of secular ritual for the new state.

From 1948 until 1967, such traditional holy sites as the Western Wall in the Old City and the ancient Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives were off-limits. While this inaccessibility may have contributed to the evolution of Mount Herzl as an alternative sacred space, other factors were at work as well.

According to the bylaws governing the area of Herzl’s tomb, public ritual in Israel has some very “religious” aspects. Entry to the site is limited during the Independence Day ceremonies, which must take place several meters from the tomb itself.

In August 1949, a member of a Ministry of Religious Affairs public committee complained to the Prime Minister’s Office about the selling of refreshments close to the tomb and protested against the site’s accessibility by vehicle. Comparing the tomb to the Western Wall, he huffed, “You can’t make a pilgrimage in a vehicle” (ISA, G 5595 file 4717 [Hebrew]).

Gruenbaum added his voice in similar protest, calling upon Ben-Gurion to guard “the sacred of the nation.” This idea of restricted access is unexpectedly similar to the traditional Jewish approach to the Temple and its Holy of Holies.

Symbols Old and New

In fact, there are more than a few examples in which modern Zionism borrows from the symbolism of traditional Jewish customs. Although the ambivalence and even hostility of the state’s socialist founders toward much of Judaism is well known, they didn’t completely reject Jewish tradition. As Berl Katznelson, architect of Labor Zionism, wrote:

A renewing and creative generation does not throw the cultural heritage of ages into the dustbin. It examines and scrutinizes, accepts and rejects. At times it may keep and add to an accepted tradition. (“Revolution and Tradition” (1934), in A. Hertzberg, ed., The Zionist Idea, 1982, pp. 392–3)

Zionism aimed not only to redeem the Jewish people but to evolve a “new Jew.” Many strove to create a new Judaism as well, combining modern humanism and equality with traditional Jewish heroism and pre-exilic Jewish ideal of freedom in the ancient land of Israel. The Exodus, the Maccabees, and Bar Kochba among other icons were reworked to highlight activism at the expense of Divine intervention. The biblical festivals underwent a similar transformation, particularly on the kibbutzim, where farmers marked the harvest by celebrating the fruits of their toil rather than thanking God.

These were the first steps in the evolution of Israel’s “civil religion.” This term, coined by Rousseau, was clarified for the Israeli context by Charles S. Liebman and Eliezer Don-Yehiya. In reconciling Jewish tradition with the needs of the state, they wrote, the traditional symbols “must be reformulated through a process of transformation and transvaluation” (Civil Religion in Israel, 1983, p. 19). Israel’s founders were well aware that “Zionism … had a special need for values and symbols of a sanctified character which would attract Jews to its ranks, integrate them into its new society, and mobilize them in the pursuit of Zionist goals” (ibid., p. 28).

Sanctified symbols have figured in secular Zionism from its inception. Physical labor, the sacred heart of Labor Zionism, was known as avoda, a term also describing the Temple service. It was no coincidence that the land being worked by the (mostly) secular Zionist pioneers was the Holy Land. Pioneer ideologue Aaron David Gordon (1856–1922) framed such labor in overtly religious terms, depicting it as the key to redemption. Gordon even explicitly connected national life and religion:

Religion knows how to impose duties, to assert its rightful place and to be intrinsically important…. Is national life … [not] valuable enough to require the same effort made by the religious Jew on behalf of religion? (Gordon, The Nation and Labor [1952], p. 126 [Hebrew])

Ahad Ha-Am is commonly characterized as Zionism’s “secular rabbi,” Gordon as its “secular mystic,” and Herzl as its “messiah.” Indeed, Herzl’s funeral in Vienna featured the emotional hordes and almost ecstatic outbursts of mourning that typically accompany the departure of a saint or rebbe.

Sacred Space Meets Sacred Time

But how, practically speaking, did Zionism integrate the religious instincts of yesteryear into a secular framework? Civil religion, like its traditional equivalent, is generally anchored both in space and in time. The most intense period of the Israeli calendar follows Passover and includes Holocaust Day (27 Nisan) and Memorial Day (4 Iyar), which merges into Independence Day (5 Iyar). But this time of year was not the only option. Alternative dates for Independence Day included November 2, when the Balfour Declaration was signed, and November 29, the anniversary of the United Nation’s 1947 decision to create the State of Israel. Choosing the date of Israel’s declaration of independence highlighted a daring, difficult step taken by Jews themselves, rather than international recognition. These Zionist “High Holy Days” also link Pesach, which marks the birth of the Jewish people and its emergence from slavery to freedom, and the rebirth of that nation from the ashes of the Holocaust. The seven days from the end of Pesach to Independence Day are reminiscent of shiva, the seven-day mourning period.

The date maximizing continuity with pre-state practice would have been 20 Tammuz, the day of Herzl’s death, long marked as a Zionist holiday. In fact, 20 Tammuz was celebrated as “The Day of the Ingathering of the Exiles” in 1948 and 1949. On this date in 1950, the Knesset passed the Law of Return, guaranteeing free immigration and citizenship for Jews coming to Israel. From 1951 onward, the theme of mass immigration was introduced into Independence Day, and Herzl’s memorial day was removed from the calendar – but not from the national consciousness. As the center of Israel’s civil religion, Mount Herzl is the natural focal point for the state rituals associated with Independence Day and indeed, since 1950, Israel’s official independence celebrations have been held close by Herzl’s tomb.

As well as the ceremony honoring the memory of fallen soldiers, these rituals have included a torch-lighting ceremony, cannon fire, a speech by the chairman of the Knesset, a marathon culminating in Jerusalem, and military parades and displays.

The elemental use of light and fire signifies redemption, heroism, and power as well as creation, while the kindling of a torch to mark the beginning of Independence day clearly resembles the candle lighting that begins the Sabbath and holidays. The traditional blessing is, of course, replaced with a secular formula.

Until 1952, the torch lighting consisted of the Knesset chairman’s igniting a single torch. This act, performed at the central shrine of Zionism and the State of Israel, drives home the central characteristic of civil religion – the transfer of ultimate authority from God to society. With Chairman Yosef Sprinzak’s lighting of the torch at Mount Herzl on Independence Day 1950, the sovereign people consecrated its temple.

Lights and Sacrifice

The torch lighting evolved out of a popular custom observed already on Independence Day 1949, even before Mount Herzl was inaugurated with Herzl’s re-interment a few months later. The ceremonial use of fire continued on Hanukkah 1949, when members of the Gadna army youth movement ran with torches from sites of Israel’s heroism past and present to Mount Herzl, where a giant Hanukkah lamp was lit. The procession was part of the central celebrations marking of Jerusalem as the renewed capital of Israel, recalling the Hasmonean hanukkah (rededication) of the Temple. The popularly perceived themes and symbols of Hanukkah – a military struggle, freedom, rededication, and light – acquired great significance in the development of the Independence Day rituals.

After the chairman of the Knesset lit the central torch on Mount Herzl that first Independence Day in 1950, the Gadna youth followed suit in settlements throughout the country. This way, the lights did not arrive at Mount Herzl but emanated from it. The press noted the parallel to the Second Temple custom of declaring the new month by lighting torches from the Temple to the Mount of Olives and outward toward the Diaspora. The marching exercises which have always formed an integral part of the ceremony also recall the military heritage of the Hasmoneans.

The nationwide torch lighting was discontinued after 1955, when the Mount Herzl ceremony was expanded to include the kindling of twelve torches – for the twelve tribes of Israel – by citizens from a variety of social sectors. Massive Jewish immigration had more than doubled the population of the state in the five years from 1948, and it was central torch-lighting ceremony was intended to symbolize the ingathering of the exiles.

Why are death and the military such central motifs of Mount Herzl and its rituals? The answer lies, in my opinion, in Israel’s civil religious values, which stress the pivotal role of people rather than God. The army, integral to the state’s survival and therefore symbolizing heroism and the preservation of independence, plays a key role at the site, in the Independence day ceremonies, and in the civil religion of Israel as a whole. Death at Mount Herzl is not incidental, but elevated to level of sacrifice. Through its military cemetery, Mount Herzl becomes a kind of Temple, the last resting place of those who sacrificed themselves for the sake of the nation. Deliberately or not, Herzl’s tombstone – a low, two-tier, rectangular black slab – even suggests an altar. The bearing of arms and the fire of cannons on state occasions underscore the military aspect of the national ethos.

Uniting the sacrifices made by the people of Israel for independence with the vision of the Jewish state personified in the character of Theodore Herzl, Mount Herzl constitutes a sort of civil pilgrimage site. How that site has been affected by the restoration of the ancient Jewish sites of the Old City and the Temple Mount warrants further inquiry. At the very least, we can echo David Wolffsohn, Herzl’s successor as president of the World Zionist Organization, at Herzl’s funeral in Vienna in 1904: “We swear to you that we will keep your name sacred and that it will remain unforgotten.” He could never have imagined how right he would prove to be.