Guerrillas in the Hills

The year 160 BCE found the Hasmonean family in a sorry state. Judah had fallen in battle, his army decimated and the Maccabee rebellion all but quashed. Seleucid king Demetrius I Soter controlled Judea with his powerful army. In the Temple in Jerusalem, it was business as usual. The religious decrees had been repealed and the priesthood restored, with Alcimus serving as high priest. Ostensibly, the rebellion should have ended there. Judah himself had made a truce with the Seleucid kingdom, and most Judeans had no problem living under foreign rule. There seemed nothing left to fight for.

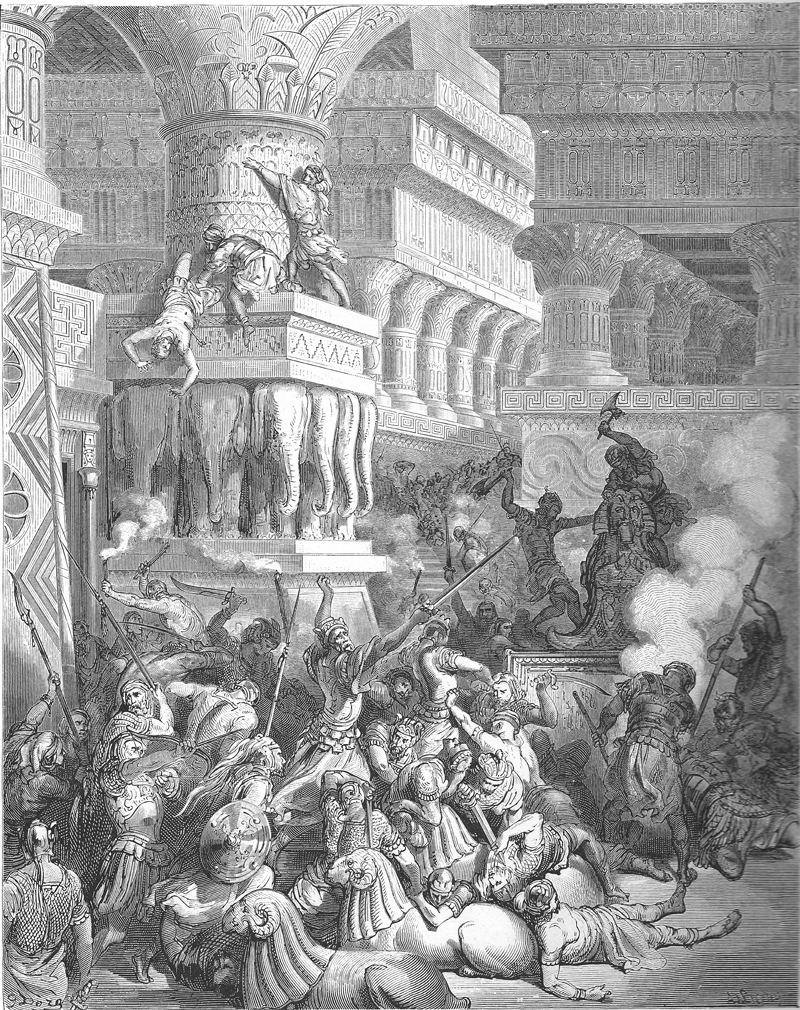

But Alcimus soon proved even worse than his predecessor, Menelaus, and the Seleucid government was too weak to protect the pious Jews of Judea. Some identify Alcimus as none other than Jakim of Zerorot, an infamous tax collector and nephew of Jose son of Joezer of Zeredah, one of the generation’s outstanding Jewish leaders. If so, Alcimus was responsible for assassinating his uncle and killing many of his disciples. In any case, Alcimus didn’t last long. Whether he committed suicide (according to the Midrash) or died of a stroke (as in I Maccabees 1:9), his death left the Temple without a high priest and the Hellenists in Jerusalem rudderless.

It was a grim picture: the Hellenist ruling class had no popular support and no one to state its case to the authorities. With no high priest, much of the Temple ritual was simply abandoned. And in the hills around the city, a group of guerrilla fighters with widespread grassroots backing struggled to maintain a toehold despite being constantly hunted down. In Syrian Antioch, meanwhile, young and energetic King Demetrius also had his problems. His popularity was eroding rapidly, and worse still, he had embroiled himself in a prolonged conflict with the emerging superpower, the Roman Republic.

Lessons in Diplomacy

Why the Maccabee rebels chose Jonathan as their new leader over his older brother Simon remains a mystery. According to the book of Maccabees, Mattathias had designated his sons Judah and Simon as military commander and political leader, respectively, leaving Jonathan out in the cold. But he turned out to be an excellent choice. Jonathan had a good eye for opportunity – and the patience to wait for the right moment to exploit it. Personal charm in no small measure helped him win the Seleucid king’s confidence, turning the latter’s anger to sympathy on more than one occasion. Cautious and sensible but also extremely shrewd, he was as skillful a diplomat as he was a warrior. From brother Judah’s alliances with Seleucid general Lysias and with Rome, he had learned that agreements with the enemy must be backed by a strong power if they are to be honored. Bitter experience taught him to see such treaties as mere stepping-stones to the next pact. And Jonathan understood that the promises made in one round of negotiations, formalized or not, came back to haunt you as the starting point for future talks.

At first Jonathan avoided direct military confrontation with the Seleucids, preferring guerilla warfare to consolidate his position in the Judean Hills. His patience paid off when Bacchides, the Seleucid general who had defeated Judah and was now military governor of the province, realized he was wasting time and resources in Sisyphean pursuit of the rebel forces. Bacchides concluded that he would be better off recognizing Jonathan, the people’s favorite, as their authentic representative instead of some member of the corrupt Hellenist establishment. Jonathan was given license to operate from Michmas, granting him official status in the eyes of the Seleucids – a turning point for the Hasmonean family. Time was also on his side. The Middle East was in turmoil, with major geopolitical changes under way – the perfect opportunity for Jonathan to prove his skills and put his keen political instincts to the test.

Expert Juggler

Instability and violence, the result of Seleucid infighting as well as regional conflict, characterized Jonathan’s fifteen-plus years of military and political leadership of Judea. He exploited this unrest, juggling the warring powers and chalking up gains for his people and country. To understand his frequent zigzags in foreign policy, we must first identify the key players.

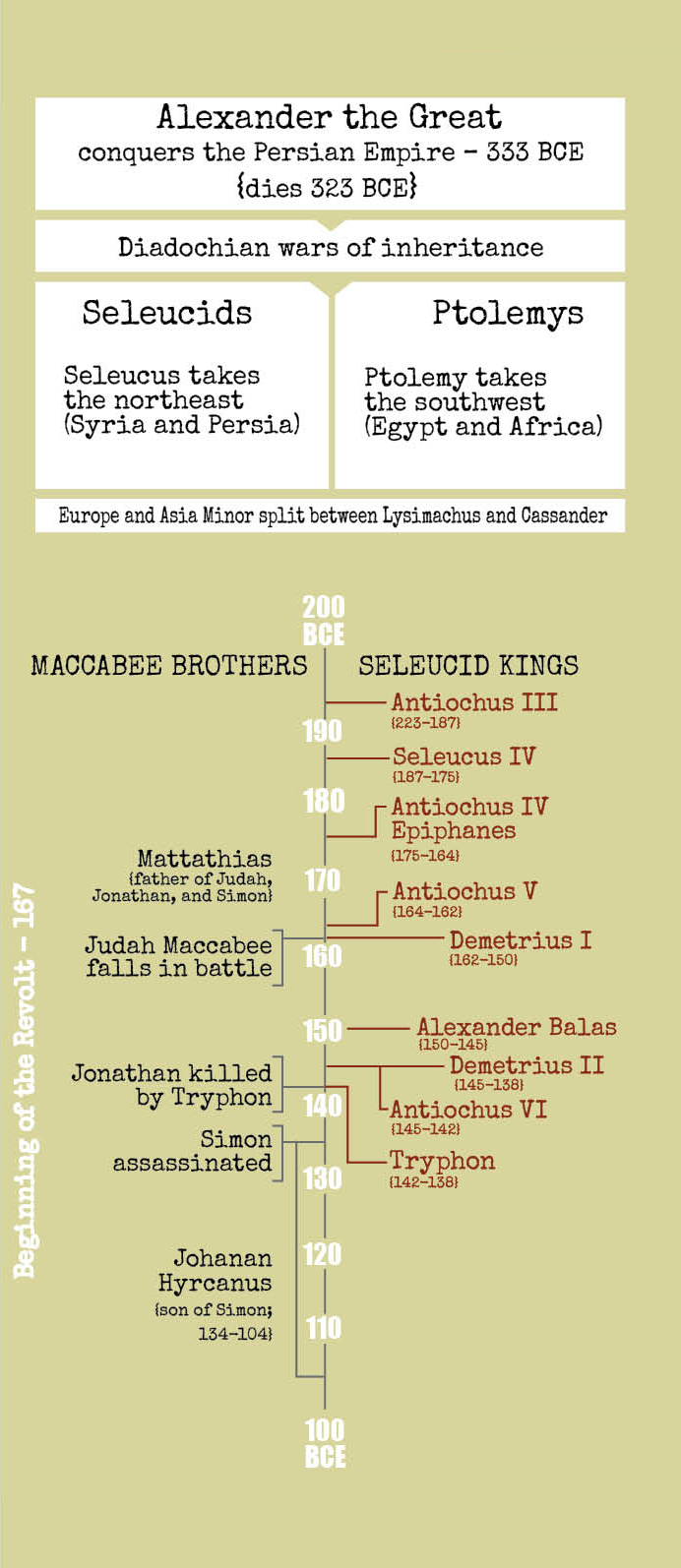

On one side of the Mediterranean Basin was Rome – the rising power and a force to be reckoned with. The Romans had already dictated terms of surrender to the warring Ptolemies and Seleucids during the reign of Antiochus III (the Great), when they held members of the Seleucid ruling family hostage in Rome. The Roman Senate took decisions as a group, so the rise and fall of specific individuals influenced policy much less than in the divided Hellenist empires, where each change of ruler could alter the delicate balance by which the Ptolemies and Seleucids alternately dominated the region. The events of Jonathan’s tenure took place against an increasingly Roman backdrop, both militarily and politically; the Roman Republic sacked Corinth and Carthage, overturning the old order and ensuring that every kingdom in the area included Rome in its calculations and decisions, including its choice of leader.

Further east, in Syria and Judea, the Seleucid Empire was caught up in a war of succession, with both Seleucus IV and his brother Antiochus IV – sons of Antiochus III– claiming the throne. Demetrius I, son of Seleucus, then killed his cousin Antiochus V, angering Rome and simultaneously falling out with all the leaders of his own kingdom. Waiting in the wings was Demetrius’ opponent, the pretender Alexander Balas, whose descent from the deceased Antiochus is disputed to this day. After Balas emerged victorious, Demetrius II (son of Demetrius I) avenged his father by moving against Balas, eventually defeating him. Antiochus VI (son of Balas) subsequently attacked Demetrius II but was killed by his own general (Diodotus Tryphon – see below). The Seleucid kingdom remained in turmoil, with royal heads rolling one after another.

Demetrius I, who killed his cousin in order to seize the Seleucid throne, was held hostage in Rome as a child to guarantee that the Treaty of Apamea – forcing his father, Antiochus III, to retreat from Balkan territories – was upheld. Coin showing Demetrius I on one side and a cornucopia on the obverse, 161 BCE

Meanwhile, in Egypt, Ptolemy VI Philometor was also mixing in, marrying off his daughter, Cleopatra Thea, to various Seleucid leaders in turn, according to his shifting political ambitions. Jonathan used the volatile political situation to solidify his own position.

Gold signet ring of Ptolemy VI Philometer (Mother-Loving), so called because he initially reigned alongside his mother, Cleopatra I. The many wars, intrigues, and upheavals throughout his life revolved chiefly around his struggle to maintain control of Egypt and reconquer Judea. Ptolemy indulged his Jewish subjects, allowing the priest Onias IV to settle in Leontopolis (near Memphis) and establish a

temple there

The rise of upstart Alexander Balas made Jonathan the decisive factor in the balance of power. Both Seleucid factions vied for his support: yesterday’s terrorist became today’s sought-after ally. This change was due as much to Jonathan’s stature and status as to Judea’s strategic position as the land bridge dividing the Ptolemies of Egypt from the Seleucids’ empire to the north and east. Both powers were desperate for a foothold in Jonathan’s kingdom.

Independent Judea

Jonathan profited repeatedly from this competition. First, Demetrius I allowed him to return to Jerusalem and rearm. Then in 152 BCE Alexander Balas appointed him high priest, after which Demetrius I exempted him from taxes. He was a guest of honor at Balas’ wedding, and in return for his support, Jonathan became the king’s adviser and was appointed meridarch (civil governor) of Judea, while his brother Simon was placed in charge of the military. His alliance with the Seleucids notwithstanding, Jonathan also secured the support of Rome, renewing its treaty with Judah. Constantly backing the winning horse, he shifted his allegiance from one side to the other (always with due cause), exploiting these twists and turns to Judea’s advantage, though it was still not considered an independent kingdom.

While Judah’s guerrillas were defeated when outnumbered in open battle, Jonathan’s men could meet his enemies head on. With an increasingly powerful army, eventually numbering tens of thousands (Judah’s forces had been much smaller), Jonathan conquered Jaffa, Ashdod, and Gaza. He even sent troops to Syria to help Antiochus VI fend off his rival, Demetrius II. This was the first time a Jewish army fought someone else’s war; the political gain was clear.

It was typical of Jonathan. The wars at home and beyond Judea’s borders, the alliances made and broken in swift succession – all were simply means of freeing Judea from foreign subjugation. Jonathan didn’t care whether he was known as the king’s confidant or as a Seleucid official. As long as Judea was independent, and the Temple ritual – debased by Jason, Menelaus, and Alcimus – could proceed according to Jewish tradition, Jonathan was satisfied.

By his untimely death in 143 BCE, Jonathan had achieved these goals. Judea was no longer taxed by a foreign power, and his family had secured the positions of high priest as well as official representative and ruler of Judea. The Pharisees, the rabbinic faction to which he belonged, dominated Jewish society. His international standing as both friend of Rome and Seleucid vassal was sound. For all intents and purposes, Judea was an independent Jewish state, run according to Torah law, with a priestly family at the helm.

The Wicked Priest?

Yet the picture was not all rosy. First, though strategically located and courted by the surrounding nations, young Judea was small and vulnerable. When Antiochus VII Sidetes decided to move against Jerusalem just a decade later, in 134 BCE (early in the rule of Johanan Hyrcanus), there was nothing to stop him, and Judea once again found itself under Seleucid control. But Jewish independence was not entirely lost. Hasmonean rule remained firm, the army grew (thickening its ranks with foreign mercenaries), and the country even minted its own coins.

Second, although the pietist faction led by the Hasmonean family had ostensibly overcome the Hellenists, Greek influence was strong. Jonathan almost certainly communicated with the world at large in Greek. He signed a treaty with the powerful Greek city-state of Sparta, and the trappings of his kingdom – the royal robes and gold crown as well as his titles – were entirely Hellenist. Jonathan’s children and grandchildren, the second- and third-generation Hasmoneans, hired pagan soldiers and bore Greek names. And the Hasmonean family burial complex built by Simon featured pyramids and drawings of ships and vines – all Hellenist symbols.

There were even more significant chinks in the Maccabees’ armor. Jonathan had been appointed high priest by the Seleucid Alexander Balas, much as a generation before, another foreign ruler had installed Menelaus. (Only that appointment had sparked the Hasmonean revolt, whereas this one was seen as a mark of its success.) Jonathan’s dual role, effectively uniting “church” and state, had critical ramifications and was sharply criticized in some circles.

Although the historic sources are inconclusive, Josephus divides Jerusalem’s religious Jews into three factions – Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes – squarely under Jonathan’s leadership. The significance of these groupings was not fully appreciated until the discovery and publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which shed new light on Jewish society in Jonathan’s generation. In the scrolls, members of the Dead Sea sect refer to their leader and founder as the Teacher of Righteousness, while his enemies include the Angry Lion, the Man of Lies, the Wicked Priest of Jerusalem, and Seekers of Deceits. Many historians, including the late Prof. Hanan Eshel, identify the Wicked Priest – who almost destroyed the sect in its early days – as none other than Jonathan the Hasmonean:

who was called loyal at the start of his office. However when he ruled over Israel his heart became proud, [and] he deserted God and betrayed the laws for the sake of riches. (“Pesher to Habakkuk,” trans. Elisha Qimron and John Strugnel, The Dead Sea Scrolls Studies Edition, ed. Florentino Garcia Martinez and Eibert Tigchelaar [Wm. B. Eerdman’s Publishing], p. 17)

It was Jonathan, then, whom the leaders of the sect petitioned to abide by their understanding of the laws of ritual purity in the Temple:

[And also] to you we [have written some of the precepts of the law which we think are goo]d for you [and for your people], [f]or we saw [that you have intellect and knowledge of the Law. Reflect on all these matters and seek] from Him [that He may support your counsel and keep far from you the] evil scheming. (4QMMT 28–32, “Halakhic Letter,” trans. Elisha Qimron and John Strugnel, in Scrolls Studies, p. 805)

Not only did Dead Sea sectarians disagree with the Hasmonean priests (who generally sided with the Pharisees) on questions of Jewish law, they saw Jonathan and his descendants as usurpers of the high priesthood from the historic priestly family of Zaddok. Having defeated the Hellenists, the Pharisees now grappled with radical Zaddokites (or Sadducees) alongside messianists and other dreamers. The conflict covered all areas of Jewish life – and death. Whereas the Sadducees based their observances on the Five Books of Moses, the Pharisees deferred to the Oral Tradition handed down over the generations, while the Dead Sea sect (also known as the Essenes) claimed divine inspiration as its guide. The sect even had a different calendar.

Did this spiritual tension spell the beginning of the end of the Second Temple period? What would Jonathan’s reaction have been had he realized the long-term consequences of his conduct? He certainly could not have imagined that his heirs would break ranks and become Sadducees.

What’s more, the social idealism of the isolationist Dead Sea sect may well have produced the wandering reformers who later founded an entirely new religion. Who could have believed that Jonathan and his divisive policies would pave the way for the emergence of Christianity, whose adherents would persecute the Jews for thousands of years?

The End of the Beginning

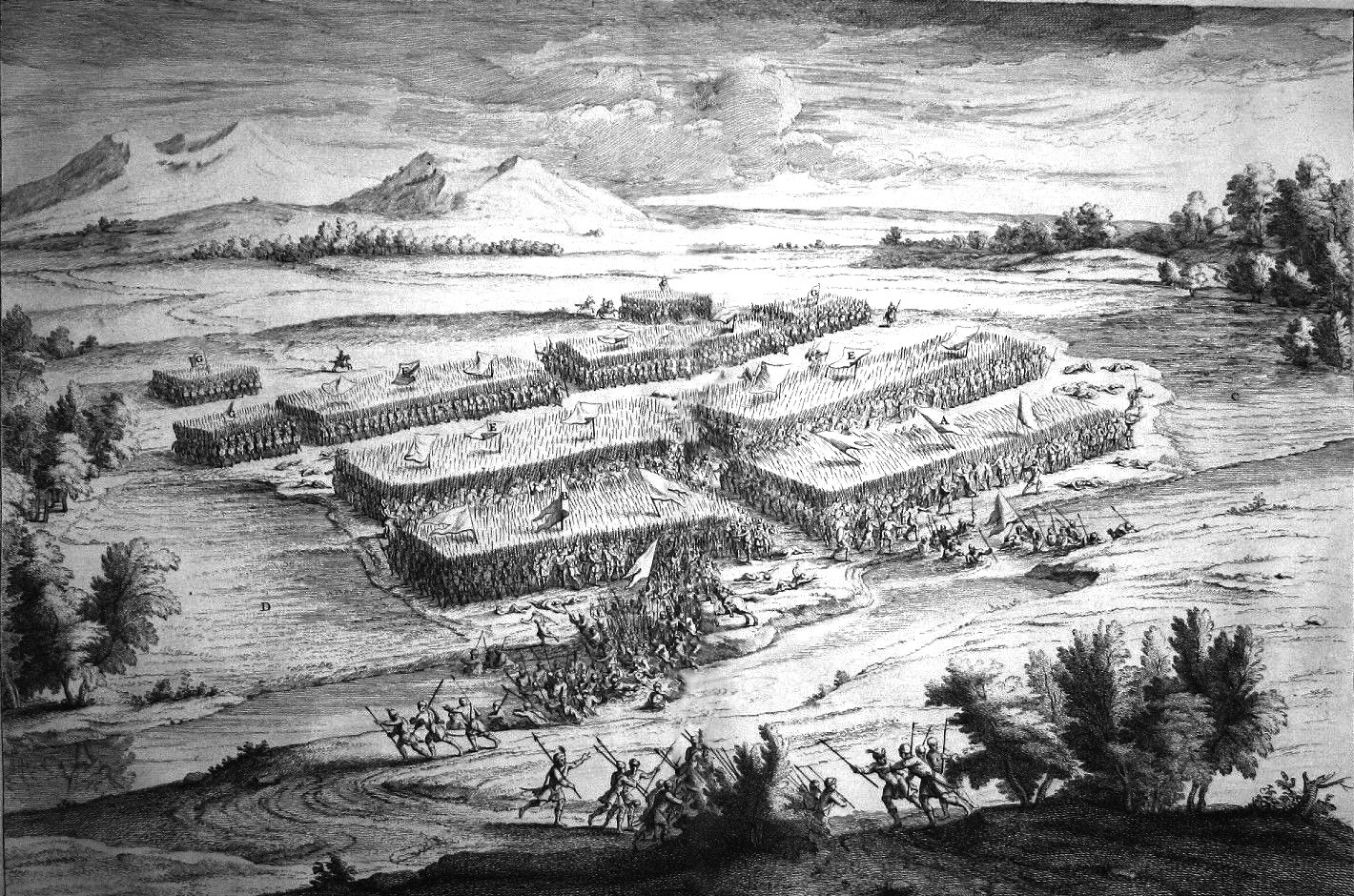

Predictably, Jonathan’s downfall was swift and sudden. In another round of civil war in Seleucia, Diodotus Tryphon, Antiochus VI’s general and therefore Jonathan’s ally, switched sides and tried to assassinate the young Antiochus and seize the crown for himself. But he worried that Jonathan, who had proven his strength in the past, would come to Antiochus’ rescue. After declaring war on Jonathan, who arrived in Beth She’an with forty thousand soldiers to meet Tryphon’s challenge, the wily Syrian tricked him. Pretending to have come in peace, Tryphon persuaded Jonathan to discharge his army in return for control of several towns plus taxation rights that had been promised him by Demetrius II, Antiochus VI’s rival. Jonathan fell into the trap and was taken prisoner.

After dragging the Hasmonean ruler along with him on his military campaigns in Judea, Tryphon realized he couldn’t overcome the Judean army, now commanded by Jonathan’s brother Simon. Thwarted by heavy snowfall in the Judean Hills, the general headed home. Simon paid an exorbitant ransom of gold as well as returned captives, but Tryphon killed Jonathan anyway.

Tryphon’s duplicity did him no good, however. Judea’s international standing was unharmed. Simon kept the kingdom stable, while rivals vying for the Seleucid crown continued to woo the fledgling Jewish state. Jonathan the Hasmonean had been the leader of Judea for eighteen years, more than his predecessor, Judah, and his successor, Simon, together. Hounded at first by Judea’s Seleucid overlords, he came to be seen as a respected ally whose political and military power had to be taken into account by all kings of the area. As both high priest and Seleucid official, Jonathan was a formidable figure. After forcing the Hellenists out of Jerusalem, he expanded his country’s borders at the expense of its traditional enemies. Though he founded no dynasty, and the Hasmonean kings descended from his brother Simon, their kingdom could never have come into being without Jonathan, nor could Simon have earned the sweeping recognition from his people that formed the basis of their power.

Brilliant and sophisticated, Jonathan could also be described as unscrupulous. When it came to restoring Jerusalem’s glory and establishing Jewish rule under Hasmonean leadership, the end, as far as he was concerned, justified every means. Yet Jonathan’s victories solved some problems while creating others. He may have diverted the danger of paganism, but in its place came the internal friction that eventually led the young kingdom of Judea to disaster.