Attack and Honor

On the morning of August 20, 1914, the sun shone brightly on the fields of Lorraine. Forty-four years had passed since France had been humiliated by the German conquest of Alsace-Lorraine. Now, at the slightest hint of German aggression, the French army was determined to reclaim these two predominantly French provinces. Forty-four years of careful planning and an entire nation thirsting for revenge formed the backdrop to the start of World War I.

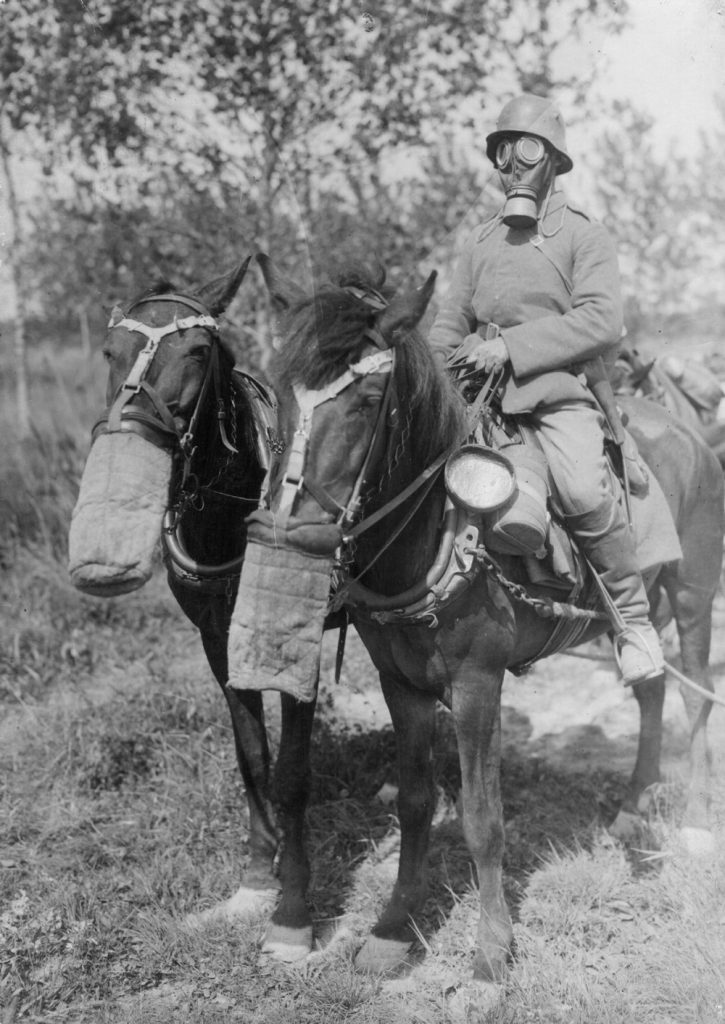

Gas masks appeared at the front just days after the first gas attack, with improved models following swiftly on their heels. The modern machine gun had already been invented by Hiram Maxim in 1884, but European armies vetoed it as dishonorable, limiting its use to colonial warfare. World War I swept away all such scruples. British soldiers protected by gas masks fire a Vickers gun, July 1916

At the heart of French military strategy was Plan 17, a secret scheme devised by the General Staff, describing the army’s deployment for invasion of the German-occupied provinces in minute detail. Following this incursion, a military offensive was to advance deep into enemy territory, striking a fatal blow to the capital, Berlin. French troops still marched to the beat of Napoleon’s “doctrine of the offensive,” and to quote French general Ferdinand Foch: “There is only one way of defending ourselves – to attack as soon as we are ready” (Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August [New York: Ballantine Books], p. 233). Defense was akin to disgrace; retreat was unthinkable. The French army’s guiding principles were attack and honor.

Miscalculations

And so, on that summer morning, the French army divisions, conspicuously dressed in their traditional red trousers and blue shirts, polished helmets glinting in the sun, prepared to attack. The officers, white-plumed graduates of the elite Saint Cyr military academy, adjusted the fit of their gloves as if for a ball. The heart of the nation throbbed at the approaching liberation of Lorraine; everything was set for a French victory that would wipe out years of shame.

The French senior command had drilled its troops according to precise calculations. In the twenty seconds it would take the enemy to raise its weapons, take aim, and fire, French soldiers were to advance fifty meters to the German trenches and neutralize their opponents. A light artillery barrage was to keep the Germans in the trenches, rendering their fire even less effective.

But the French had miscalculated. Well camouflaged in khaki uniforms and entrenched in fortified positions, the German army awaited the onslaught. Armed with powerful new machine guns, they could return fire within eight seconds. Undeterred by the French light artillery, they turned the fields of Lorraine into a vast death trap for hundreds of thousands of young Frenchmen. At the end of the day, all that remained of the French pomp and glory was a grotesque pile of densely packed corpses. It looked “as if the place had been swept by a malignant hurricane” (ibid.), leaving a terrifying silence in its wake.

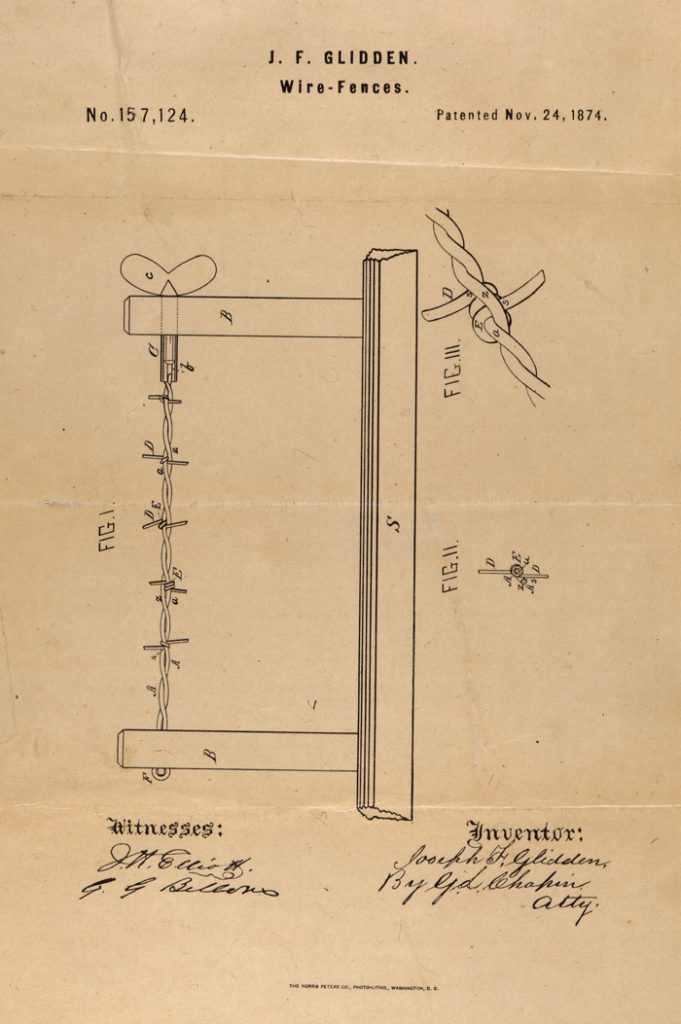

Barbed wire fencing was a devilishly simple invention put to lethal use at the front. Electrical charges made these fences doubly effective. Sign in German on the Belgian-Dutch border in World War I, warning of an electrified fence

The debacle came to symbolize the entire war, rendering Napoleon’s doctrine obsolete. France had been rudely awakened and thrust into the harsh military reality of the 20th century. Its error had resulted in crushing defeat.

Effective Entanglement

World War I, in which millions lost their lives, lasted just over four years. An assortment of nations bound by complex and sometimes obscure treaties fought an unremitting, frequently incomprehensible war, with battlefields scattered far and wide. Often regarded as the beginning of the 20th century’s litany of revolutions and bloodshed (Winston Churchill called it “the terrible 20th”), the war produced many technological innovations. While World War II brought the world the atom bomb, the computer, guided rockets, and jets, World War I also spawned, almost unnoticed, a multitude of military and civilian developments that affect our lives to this day. With the passage of time, however, the technological legacy of the Great War – as it was shortsightedly dubbed – has been largely overshadowed by the greater social and political changes that followed, wrought by Communism, Fascism, and nationalism.

The most destructive invention of the First World War originated about forty years earlier in the American Midwest. To control his large cattle herds, farmer Joseph Glidden fashioned a fence out of steel wire embedded with clusters of metal spikes, or barbs. Although barbed wire had served military purposes before World War I, it now became the ultimate deterrent. Easy to use and quick to install, barbed wire fences hindered any advancing infantry. Soldiers attempting to storm trenches swiftly became entangled and fell easy prey to enemy fire. Though heavy shelling could tear the wire fencing – especially when time-fuses delayed explosions for maximum effect – barbed wire really met its match only with the introduction of the tank (see below).

Another feature of World War I was the widespread use of machine guns, then known as firing machines. The Gatling guns of the late 1800s had to be manually cranked, were extremely cumbersome, and frequently jammed. Just prior to World War I, however, more sophisticated models were developed, operating on a principle still in use today – a cocking and reloading mechanism that utilizes the gas emitted by the bullet just fired. A cooling device was then added to prevent overheating. The new weapons could be operated by a crew of two – a gunner and an assistant to carry the ammunition – and accurately fired hundreds of bullets a minute without requiring reloading. The guns were also portable. In short, the effect was devastating.

The combination of carefully positioned machine guns and barbed wire fences made lines of defense almost impenetrable. Infantry and cavalry assaults became useless, but millions lost their lives before the lesson was learned. A century earlier, the British had held out against Napoleon at Waterloo solely by deploying about ten thousand troops along each kilometer of battlefront. Thinner lines of defense would have been breached. In 1914, by contrast, a deployment of two thousand troops per kilometer could easily withstand almost any attack. The result was a four-year stalemate on the Western Front, and a generation of young men slaughtered.

Flying and Rumbling

Many new weapons were conceived in an effort to break this deadlock. One of the most famous is the tank. Harnessing the automotive technology of the late 19th century, tanks were gradually introduced on the battlefield in increasing numbers, thanks to mass production. Improved navigability and armor plating also played their part. Although attempts had been made to develop an armored vehicle as early as 1903, the Allies built the first operational tanks only in 1915. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, was instrumental in commissioning their development and pioneering their use. By 1917 tanks had become an effective weapon, and by the time of the Allies’ major offensive in the summer of 1918, the vehicles were in widespread use.

Italian flying ace Baron Francesco Baracca poses with his Spad XIII, the plane that downed countless enemy aircraft. Such exploits remain among the most difficult and dangerous military operations, lending pilots an aura of heroism and fame

Yet even the most sophisticated tanks were unreliable and mechanically inadequate. Slow and cumbersome, they frequently broke down after just a few hours. As a result they had little real impact on the battlefield. Mainly they protected advancing infantry, significantly reducing losses. Only during the German blitzkrieg of the Second World War, twenty years later, did armored divisions become a decisive factor in warfare.

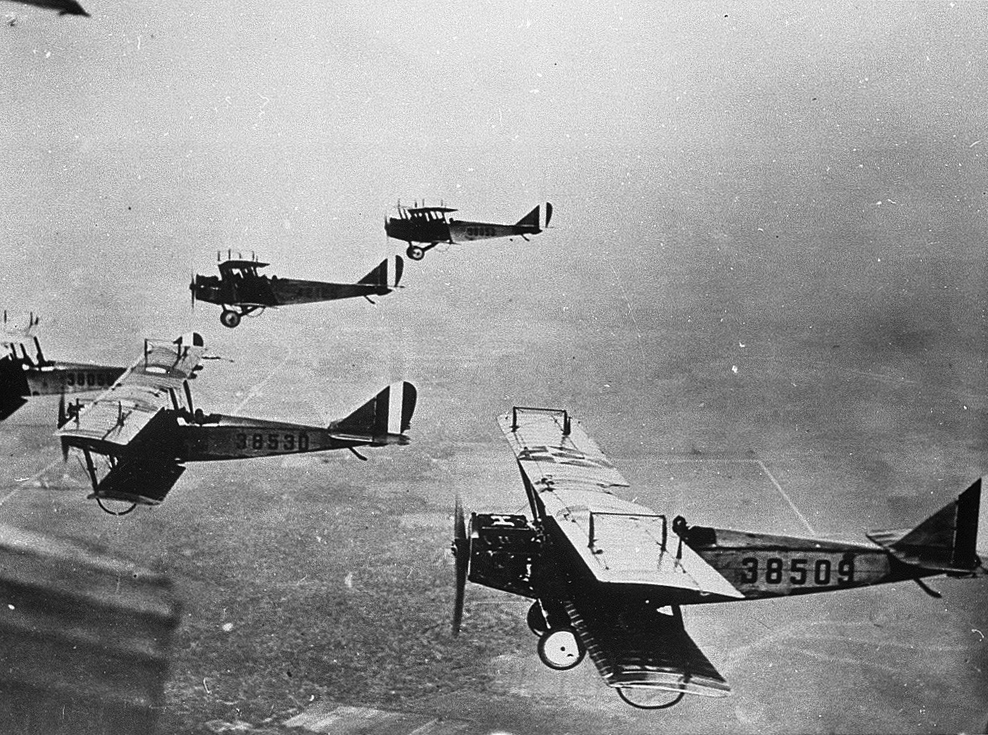

The airplane also made its military debut in World War I. Invented by the Wright brothers in 1903, light aircraft initially replaced manned hot-air balloons for surveillance. Even the early, crash-prone flying machines were considered safer than the gas balloons. Soon planes were used for short air raids. Once both sides realized the potential of air power, a battle for the skies ensued. Thus began the German “flying circus,” headed by legendary commander Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Richthofen downed about eighty enemy aircraft before his own crashed in Allied territory in 1918. Despite the wholesale slaughter going on, his enemies gave him a full military funeral, even sending photographs to the Germans. But like tanks, planes contributed little to the outcome of World War I. Although thousands were built during the war, they were used chiefly for reconnaissance.

There were other innovations and improvements as well. The submarine, invented several decades earlier, was upgraded during the war, while antisub techniques were also developed, including depth charges and sophisticated sonar equipment, such as the hydrophone. And although the walkie-talkie had been invented before the war, it was now greatly improved and became an important command and control tool.

The gradual development of the internal combustion engine in the 19th century made the war’s new heavy weaponry – the tank and the airplane – possible. Above: American JN-40 planes; below: a British tank

Dirty Weapons

The most horrific innovation of the war was poison gas, introduced by the Germans in the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. Both sides used chlorine, mustard gas, and early forms of nerve gas in an effort to break the long stalemate. The gas inflicted gruesome injuries: chlorine damaged lung tissue, resulting in death that resembled asphyxiation or drowning; mustard gas caused blindness and skin injuries; and other gases burned and affected the nervous system.

Looking back, neither side gained much from the use of gas; wind conditions made it unreliable, sometimes sending the gas back to suffocate the side that had activated it. Liquid gases (such as mustard) were easier to control but contaminated enemy territory so severely that the attacking army couldn’t press on after the gas had done its work. Soldiers were soon equipped with increasingly sophisticated gas masks and simple protective clothing. The use of this weapon therefore declined as the war wore on. In his famous poem Dulce et Decorum Est (It Is Sweet and Fitting [to Die for One’s Country]), published posthumously after the war, British poet Wilfred Owen describes the horrific suffering of a comrade-in-arms who donned his gas mask too late. (See “Dying in Vain,”

p. 25.) Generations growing up on such poems understood how much pointless suffering was caused by the Great War.

Whereas tanks and aircraft became standard issue in subsequent conflicts, chemical weapons were rarely used after the First World War, despite fears of their resurgence in the Second. While chemical warfare was largely ineffective against battle-equipped troops, military leaders may also have concluded that this was a line not to be crossed, even in war.

The Nazis didn’t hesitate to unleash hydrogen cyanide (Zyklon B) in the death camps, however. The French had used a similar substance in World War I, and the idea of utilizing gas for mass murder was apparently conceived during the war.

Ironically, gas warfare was the brainchild of a German Jewish scientist, Fritz Haber, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for inventing chemical fertilizers. The Allies had their own Jewish scientist, Chaim Weizmann, whose contribution to the British war effort paved the way for the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Britain pledged to work toward the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Saving Lives

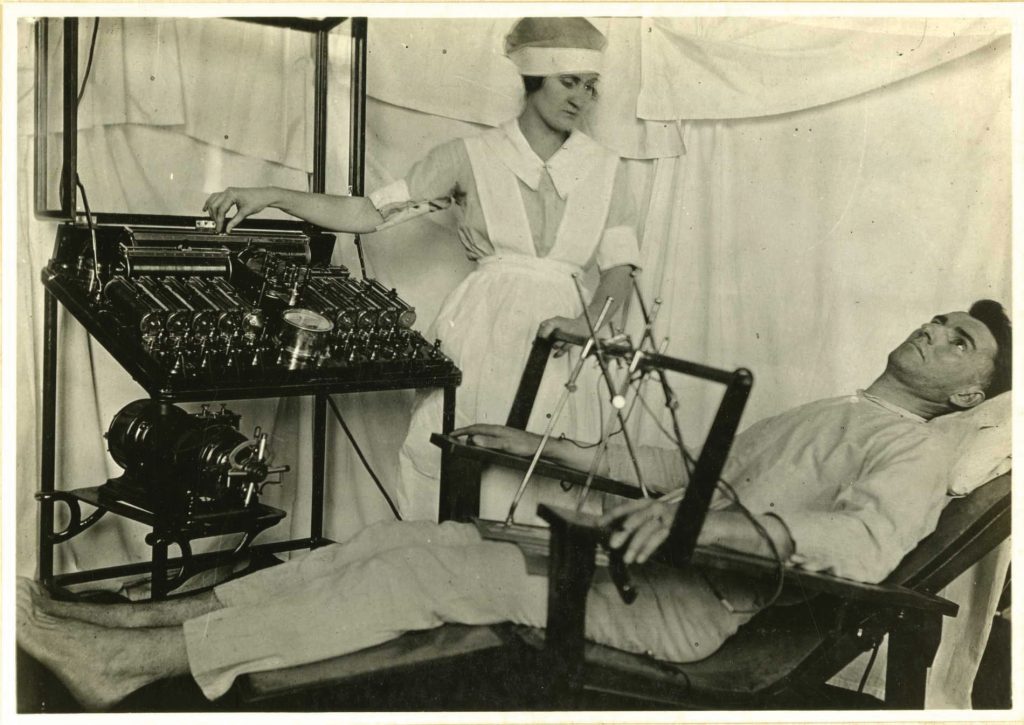

Though methods of death and destruction became more “efficient” in the course of the war, medicine too advanced significantly, especially in treating trauma due to loss of blood. Blood had already been categorized into types A, B, and O at the beginning of the century, but only in the first year of the war were anti-clotting substances developed, allowing blood to be stored for several days. Military hospitals soon began storing blood for future use, particularly ahead of major offensives. Blood transfusions saved many hemorrhaging soldiers, and blood banks – now taken for granted – were established. Infusions were also introduced to stabilize blood pressure and provide the body with essential minerals, saving countless lives.

Several field hospitals were equipped with the portable X-ray machines developed by Marie Curie. Their use before and during surgery allowed doctors to locate shrapnel and other foreign matter that had penetrated the body.

Although antibiotics were discovered only in 1928, coming into widespread use in the 1940s, the treatment of severe infections developed considerably during the First World War. The resulting disinfection methods were used for years afterward. In addition to bullet wounds and shell injuries, many soldiers succumbed to poor hygiene at the front, making sanitation a new priority. Innovative sterilization procedures lowered the incidence of infectious disease; many of these remain standard today.

Plastic surgery and prosthetics were another medical breakthrough. Thousands of soldiers and civilians lost limbs in the crossfire, and many benefited from pioneering plastic surgery techniques and the fitting of prostheses. Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, was established in England for facial reconstruction, laying the foundations of modern plastic surgery.

Post trauma, better known as shell shock, was first diagnosed in World War I. With symptoms ranging from hysteria and disorientation to partial paralysis or loss of speech and vision, victims were initially accused of cowardice and faking their conditions; many soldiers executed for insurrection almost certainly suffered from shell shock. Patients underwent such radical “treatments” as solitary confinement and electric shocks. But as the war dragged on, their symptoms came to be better understood, and special units and hospitals were set up. Physicians and psychoanalysts developed new treatments, including cognitive behavioral therapy, which became a mainstay for soldiers who emerged from the war physically whole but emotionally broken.

Gauze pads were developed almost by accident, when nurses in French military hospitals discovered that cellulose-absorbent bandages were far more effective than anything else.

The huge number of horrific casualties in World War I stemmed mostly from the dreadful mismatch of 19th-century military tactics and 20th-century technology. At first, all parties relied heavily on cavalry, just as they had in the Franco-Prussian War, which had ended in 1870. Back then, as in the earlier Napoleonic Wars, offensives had been the key to success. But by the early 20th century, trench warfare and sophisticated new weapons had altered the equation. The world learned the hard way that when troops lacking mobility face excessive firepower, the result is carnage.

A mere twenty years separated the end of the First World War I from the beginning of the Second. During that period, a generation of children grew up, only to be used as cannon fodder as well. This time, the lightning attacks of the German blitzkrieg would tip the scales once more. Yet the upper hand remained largely a function of improvements in technology.

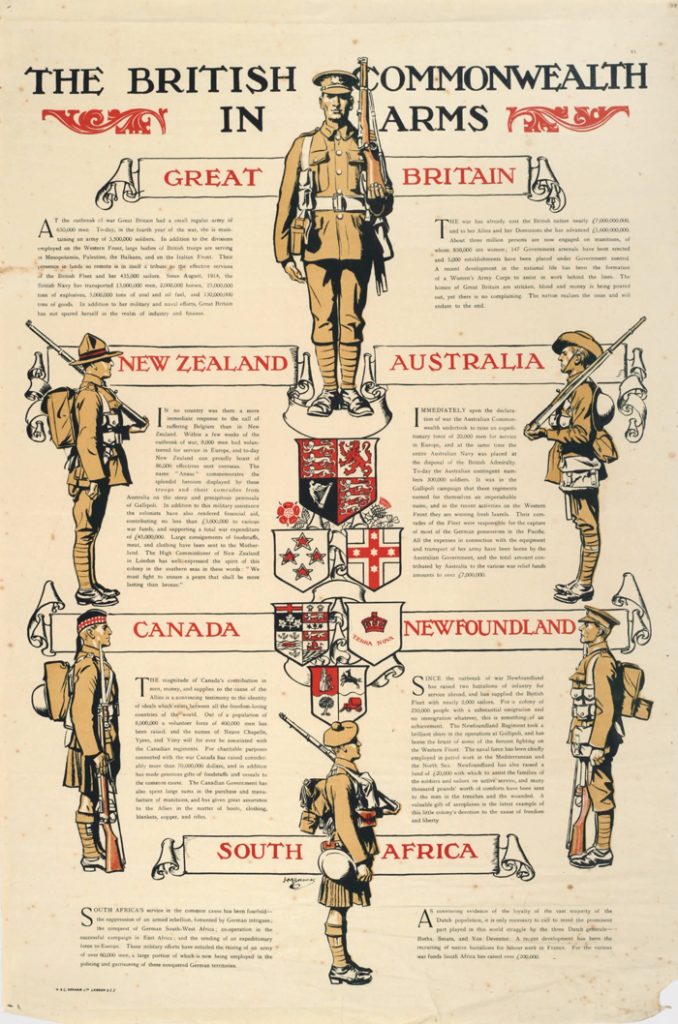

Though most armies had adopted camouflage uniforms before the war, the French retained their red pantaloons and blue shirts. Many British dress uniforms also had various colorful, obsolete features, the kilt being a prime example. Poster showing the uniforms of different nationalities within the British imperial army