Meeting in the Casbah

Israel’s Operation Peace for Galilee (June 1982–May 1985), a military campaign that developed into full-scale war with far-reaching consequences throughout the Middle East, changed the lives of many Israelis forever. One small piece of that conflict was the story of a Torah scroll IDF forces found in the Lebanese city of Sidon, and its connection with Danny Brenner, one of the paratroopers who conquered the city. This story is for him.

Passing through the old city near the bridge leading to the Crusader monastery, we noticed an intelligent-looking, bespectacled man. Stopping our armored car, we listened to him in astonishment: “My name is Yitzhak Halevy; my whole family lives in the Casba.” What could we do? … operations were halted, and we escorted him to a house where we found his aunt, her two daughters, the grandmother, and a small child – all of them Jewish. Many years ago, they told us, one of the houses served as the synagogue of Sidon. We showed them our map, and they gave us a rough location. They were certain that the synagogue contained a Holy Ark and ancient Torah scrolls concealed behind a wooden panel nailed to the wall. … Suddenly I had a powerful urge to find that Torah and return it to Israel, to the synagogue where Danny Brenner – the religious soldier killed in the battle [for Sidon] – had prayed. (From the diary of Captain [Res.] Rafi Gil, assistant commander, 7056th Battalion of the Northern Command paratroopers’ reserve unit, day five of the Lebanon War)

Operation Peace for Galilee was intended to root out the Palestinian terrorist organizations, mainly Fatah and the PLO, which had taken over Lebanon in the late 1970s in the wake of Lebanese civil war. On June 4, 1982, an Israeli air force bombardment destroyed nine PLO installations in Lebanon, whereupon the terrorists fired five hundred Katyusha rockets on civilian targets in the Galilee. Two days later, IDF forces advanced into Lebanon, and war began. The army moved north along four main axes – the coast, the central mountain area, the east bank of the Zaharani River, and the Bekaa Valley. A paratrooper battalion accompanied by armored units disembarked north of the Awali River, cutting off Fatah headquarters in Beirut from terrorist bases in southern Lebanon.

Fire from Hell

The 7056th Battalion was called up that Sabbath, and by Sunday night its paratroopers had crossed the border. The regiment entered Tyre the next day, conquering the ancient Lebanese city with relative ease. Thousands of residents were evacuated to the coast, to be received by the International Red Cross. Monday at dawn, the battalion moved up the coast toward Sidon. In his diary, Gil describes the difficulties of keeping an entire regiment moving with thousands of IDF vehicles jamming the main traffic arteries. Reaching the outskirts of Sidon, they encountered powerful terrorist resistance for the first time: a hail of bullets and antitank missiles resulted in the war’s first casualties. Burning soldiers leapt from one of the tanks escorting the paratroopers and were shepherded into a nearby building for first aid.

Photo: AP

Photo: APArmy traffic jam. Thousands of IDF vehicles choked the Lebanese coastal road north of Rosh Hanikra, making maneuvers incredibly difficult. IDF forces at the entrance to Sidon, 1982

Heavy fire from the high-rises surrounding Sidon’s main square held up IDF forces at the entrance to the city. The paratroopers couldn’t gain control of Sidon’s main arteries without first capturing the square, so the 7056th Battalion’s Company C was sent to detour through the orchards around the city and capture the houses adjoining the square. “We were attacked by friendly fire on our way through the orchards,” one combatant recalled. “Not everyone knew about the operation, and they thought we were terrorists. Luckily no one was hurt.”

Regrouping on the edge of the square, platoon commander Noam Wozner sprinted across, leading his fighters toward the tall buildings on the other side. They came under intense fire the second they were exposed, but Wozner kept moving, trying to work out where the bullets were coming from. “They were firing on us from all directions,” Bakish, the sergeant, remembered. “Noam was already more than halfway across the square with part of the company when Danny Brenner was killed. We picked him up and ran with his body to the other side of the square.”

The company was now split into two units – two platoons with Wozner on one side of the square, and one platoon with Gil on the other.

Fighting continued all night. Fierce house-to-house combat cleared the terrorists out of certain buildings, but the company was still cut off from the rest of the battalion, and sniper fire from the tall buildings stopped anyone stepping into the square. Wozner wouldn’t let troops risk trying to reach them to evacuate Brenner’s body and another soldier who’d been injured in the leg. All night terrorists kept trying to sneak up and attack, but each time they were rebuffed.

At daybreak the platoons went back to securing the square house by house, now aided by tanks, artillery fire, and aircraft, which effectively wiped out the high-rises around it. Brenner’s corpse was placed on a tank that retreated to the rear. Then suddenly:

The jets up above rained down millions of flyers, and megaphones announced that all citizens should leave the shelters, as there was no longer anything to fear from the Palestinian terrorists. Then, though none of us understood how and why the fighting had ended, deathly silence fell on all our forces. In minutes the whole square was flooded with tens of thousands of men, women, and children, all waving white flags. The injured, the dead, surrendering terrorists…. White sheets were hung out from the hospital just fifty meters away…. I gave orders to cease fire, turn on the emergency generator, and not remove nurses, doctors, or patients’ relatives from the hospital.

Finally, after so many hours of uninterrupted combat, tears began streaming from my eyes, in front of the soldiers, in front of the captured Lebanese; suddenly we were all weeping. Even fighters, it seems, can cry…. Suddenly I felt that though I was just a small cog, I was at the center of events, with the larger picture all too clear. And we had the ghastly feeling that we’d been fighting in a city packed with innocent people cowering in their shelters while everything around them was being demolished…. and I was glad that I’d cried.

One Jew in a Sea of Terrorists

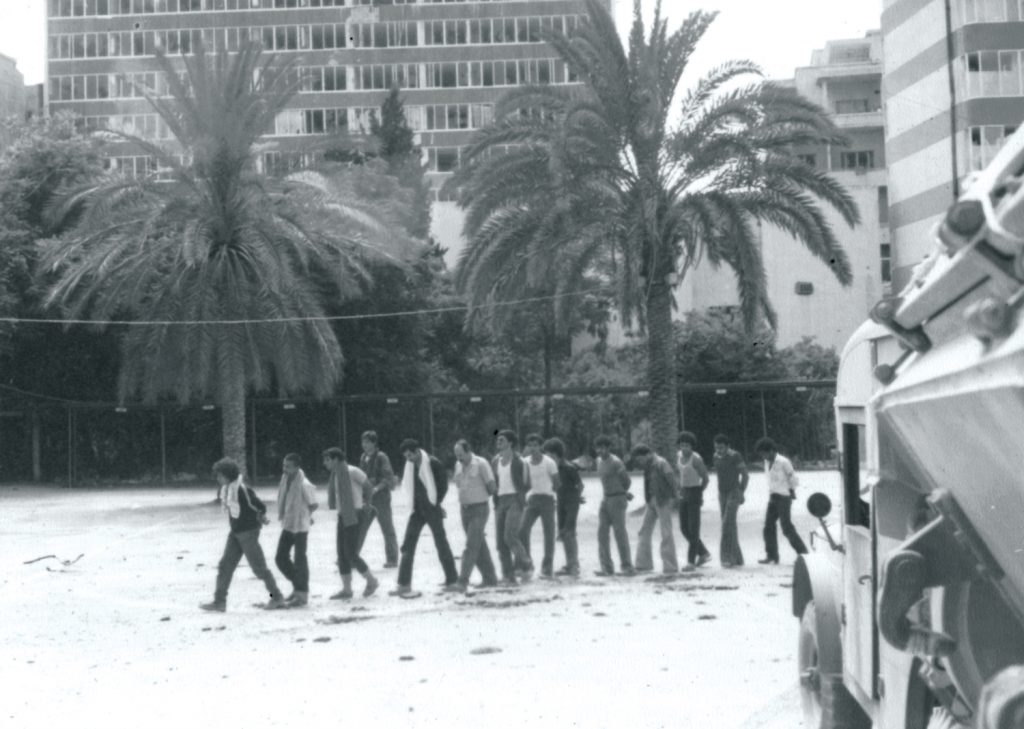

The clean-up operation in Sidon took longer than expected. The paratrooper battalion stayed in town to keep the central arteries clear while other forces pressed on northward to Beirut. House-to-house fighting continued in an effort to rid the town and adjoining refugee camp of terrorists. In what Gil called “the dirty work,” men congregated on the beaches where collaborators identified terrorists hiding among the civilian population. Hundreds were captured or killed over the next few days.

Some of the hundreds of Palestinian terrorists taken prisoner in Sidon

Photo: Avi Aviel

Photo: Avi AvielEnormous stores of weapons and ammunition were found in many of the houses searched by the IDF. Combat soldiers from Danny Brenner’s battalion with Kalashnikov rifles confiscated from a home in Sidon

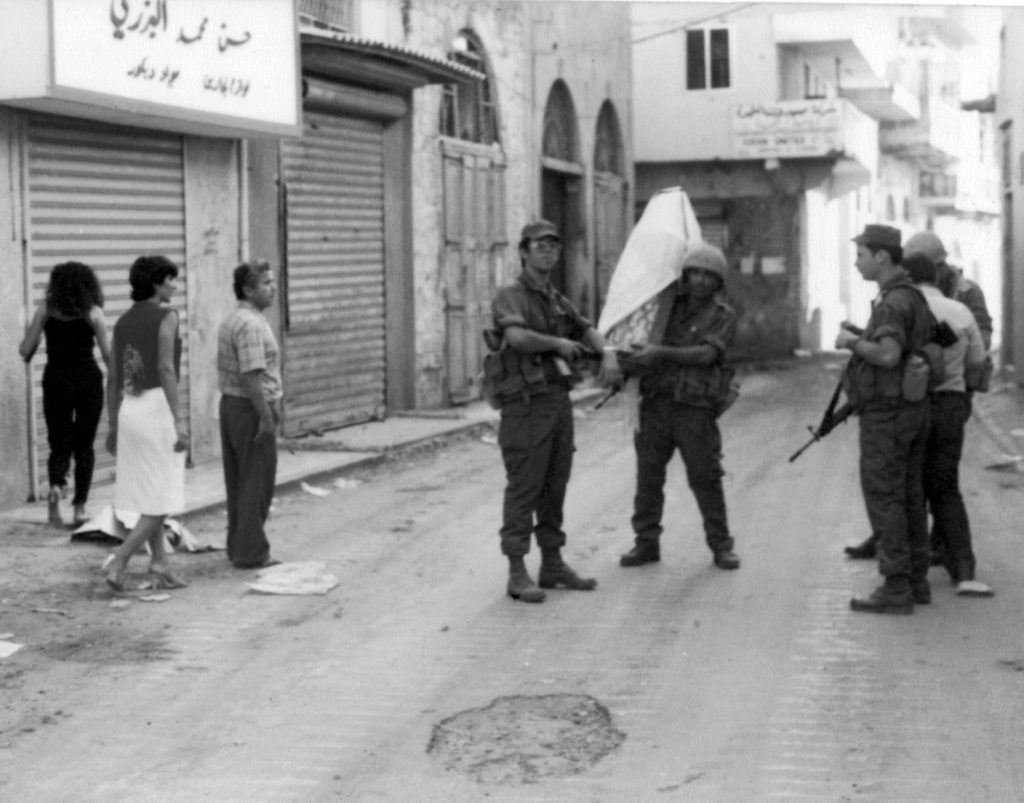

On Friday, June 11, “All of a sudden a man wearing a beret came running toward us shouting in English,” recalls radio operator Avi Aviel. “I thought he was a terrorist and nearly shot him before I realized he was calling out, ‘Don’t shoot, I’m Jewish!’ His identity card confirmed that he was Yitzhak Halevy. I followed him to his house with another soldier, where we found other members of his family. Deputy Commander Gil soon joined us, thinking we’d lost our way back.”

A lone Jew in PLO territory. Yitzhak Halevy with paratroopers. He and his family were later moved to Israel. Third from left: Rafi Gil, deputy battalion commander

Halevy told the paratroopers the secret history of his family and of a Torah scroll hidden in the town. The Jewish community of Sidon was apparently founded in the 10th century. It absorbed Jewish refugees from various other locations but remained small and concentrated in the Jewish quarter, in the northern section of the old city. With the outbreak of civil war in the 1970s, most of Sidon’s Jews migrated to Israel or North America. Halevy’s family fled too, but as a synagogue beadle, he felt an obligation to stay, along with a few close relatives. The emigrants took most of the community’s elaborate Torah scrolls with them, but the Torah belonging to the Halevy family stayed behind.

That Friday, just before the Sabbath, Gil’s men and the regiment rabbi set out to rescue this last Torah scroll in Sidon. “Find it a good home in Israel,” Halevy told Aviel, who kept him posted while the battalion was in Sidon. The story of how they found the Torah is one of the most moving passages in Gil’s diary:

I took our Rabbi David and a few soldiers, and we set out in what we guessed was the right direction. We picked up Yitzhak Halevy on the way. He got into the jeep and directed us to the road closest to the Casba. We got out with our weapons and walked, fingers on the trigger, through the labyrinthine alleys that had been the Jewish quarter until 1978. The place was all squalid, narrow lanes, full of Palestinians who’d fled from Haifa and Jaffa in the War of Independence. Then we were there. We saw an old mezuza in the doorway and squeezed through into the synagogue. A family was living there in unbelievably cramped conditions. Our hearts swelled with a sense of discovery: “Eight soldiers in the old Jewish quarter in Lebanon uncover an ancient synagogue.” Halevy, who hadn’t been there for five years, broke down and cried bitterly. We gave him a claw hammer, and he pried away the three wooden boards covering the ark. Inside was the one remaining Torah scroll. Amid all the excitement, photos, and tears, Rabbi David caught up the Torah, wrapped in a prayer shawl, and carried it back on foot with his soldiers all the way to battalion headquarters. Even a heretic like me was moved.

Avi Aviel, the soldier who took the Torah scroll from the ancient synagogue and marched with it through the streets of Sidon to his battalion’s headquarters

That Shabbat, the ancient Torah scroll lent something very special to the soldiers’ makeshift synagogue:

The Sabbath was approaching. Hirsh positioned the two tractors we’d appropriated from the terrorists ten meters apart and draped a huge camouflage net between them, turning the space into an improvised field synagogue. David stood the Torah scroll in its place of honor, and almost thirty soldiers from the battalion gathered in the modest, makeshift synagogue. It was inexplicably moving: battle-worn soldiers singing Sabbath hymns in the very heart of uncircumcised Sidon.

Photo: Avi Aviel

Photo: Avi AvielA Torah scroll is dedicated in the heart of enemy territory. Paratroopers escort the scroll from the historic synagogue to their own makeshift one in the battalion compound – a camouflage net stretched between two bulldozers

A Promise Fulfilled

The battle of Sidon was still not over for the paratroopers of the Nesher division. Bogged down like the rest of the IDF in a long, wearisome war, they were on active duty in Lebanon until 1985, when Israeli forces were withdrawn and the security zone was established in southern Lebanon. But the story of the ancient Torah scroll had come full circle. Gil’s dream was realized, and it was brought to Israel and donated in memory of Danny Brenner.

Thirty years have passed since the beginning of the war in Lebanon, since Brenner’s death and the Torah scroll’s discovery. Israeli society has changed, and the war played a key role in its metamorphosis. The soldiers of the 7056th Battalion, Danny Brenner’s comrades, remain in touch with his family and make an annual pilgrimage to his grave. Their war stories are inevitably pulled out anew on these occasions, as is the tale of the ancient Torah.

Boarded up for so many years, this special scroll now has pride of place in the synagogue of Moshav Bene Darom. It’s reserved for festivals, but every time it’s opened, my heart stirs.

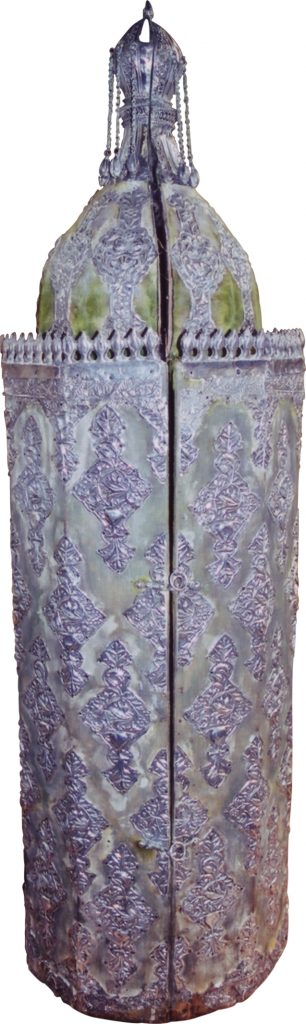

Photo: Ze’ev Ehrlich

Photo: Ze’ev EhrlichThe inscription adorning the crown of the Sephardic Torah casket (wood covered with silver-inlaid velvet) states that the scroll was written in 1868 (5628)

Photo: Miriam Tsachie

Photo: Miriam Tsachie