Belonging: The Story of the Jews 1492–1900

Simon Schama

Bodley Head, 2017

790 pages

Extraordinary Individual

Simon Schama’s magisterial Belonging: The Story of the Jews 1492–1900 begins with a false messiah who blusters his way into meeting Pope Clement VII and world dignitaries before eventually being burned at the stake. It ends four centuries later with Theodor Herzl gazing out hopefully over Jerusalem.

This ironically titled book, covering a period in which Jews belonged nowhere, brings an unwieldy subject into focus by combining wide-ranging erudition with telling details. Moving breathlessly from the Spanish Inquisition to the rise of Zionism, we meet a glittering array of Jewish entertainers, warriors, furriers, apostates, robbers, and railway barons.

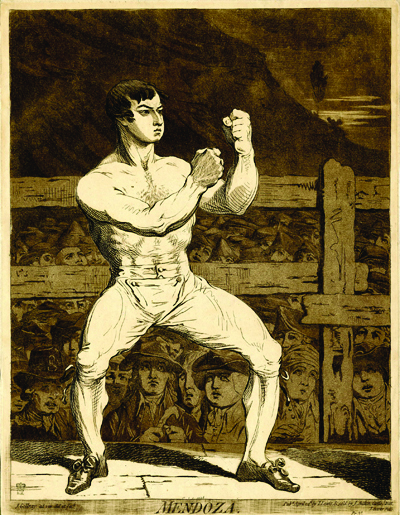

Schama lays out the spectacular variety of Jewish life. We meet Leone de Sommi Portaleone of Mantua, in northern Italy, a slightly older contemporary of William Shakespeare and a playwright in his own right, as well as a producer and author of a book on stagecraft – and spokesman of the local Jewish community. We encounter Daniel Mendoza, a Jewish boxing superstar in late-18th-century London whose career began, as he recalls in his memoir, when a bully thought, “It was a pity we were not sent to Jerusalem” (p. 348); Mendoza’s Jewishness became part of his stage persona. And then there’s Solomon Nunes Carvalho from Baltimore, photographer for John Charles Fremont’s “fifth and last disastrous expedition west in the winter of 1853–54” (p. 504). Carvalho nearly died of scurvy and dysentery, met Brigham Young in Salt Lake City, and helped found a Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Association in the tiny Jewish community of Los Angeles before returning home. The reader comes away with extraordinary tales of individual Jews but not necessarily with the story of the Jewish people. Aside from the chapter on Poland, statistics are very sparse.

Schama best describes the Jews of western Europe. Middle Eastern Jewry appears almost entirely from their perspective. Perhaps there’s a certain irony in the rootless Jew’s adoption of a Eurocentric worldview. Schama has written widely on the Jewish history of England and Holland, so his emphasis is understandable, if not always suited to the material at hand. One might be forgiven for thinking that the majority of the world’s Jews lived in Amsterdam, in England, and on the Italian Peninsula, and were performers of some sort. Obviously history favors the well-documented, even if they’re not representative. We don’t learn how most Jews lived their daily lives and what, beyond meeting their basic physical needs, occupied their minds.

A History of Schism

Intellectual history here is almost entirely about the relationship between Judaism and the outside world. One wonders if, in trying to free Jewish history of its stereotypes, Schama actually distorts it. A great deal of Jewish intellectual creativity was internal; most of it is ignored in Belonging.

One religious development that does receive a thoughtful survey is the rise of Hasidism. Much of its popularity, suggests Schama, came from rootless, vulnerable Jews’ need for a leader to protect them. “So when a choice of political allegiance in eastern Europe became a hazardous bet, it could instead be given to the protector zaddik, the righteous Hasidic patriarch, at once preacher, intercessor, visionary, and worker of wonders” (p. 466).

But no one movement or allegiance sufficed for all Jews. In fact, one theme of Belonging is infighting. In 16th-century Cochin, for instance, Sephardic Jews viewed their Indian coreligionists as inferior. “Reproducing all too faithfully Indian preoccupations with skin colour and caste, they seldom if ever shared synagogues, marriages, or food” (p. 151).

Likewise, in 1684, a Jew named Jost Leibmann was given the green light to build Berlin’s first synagogue. “No sooner had Leibmann taken advantage of this permission than a rival faction wondered out loud why it too should not have the same privilege. Theirs? I wouldn’t be seen dead in it. Feuding between the competitors became so bitter that the authorities had to step in and pacify the disputants” (p. 270).

And during the French Revolution, infighting among Jews nearly derailed their quest for citizenship. (Not that becoming citizens necessarily improved matters. Consider Alfred Dreyfus, for example.)

Schama’s “Unauthorized Glossary” contains a nugget that may give readers a sense of the author, if not of Jewish history. The entry for pisher reads: “Yiddish for a drip. You can work out the implications. The entirety of diaspora history, some Jews think, is embodied by the successive name changes of Maurice Lafontaine of Paris, who had once been Moritz Spritzwasser of Leipzig but started out in life as Moyshe the Pisher from Motol. At least his trajectory was upwards” (p. 705).