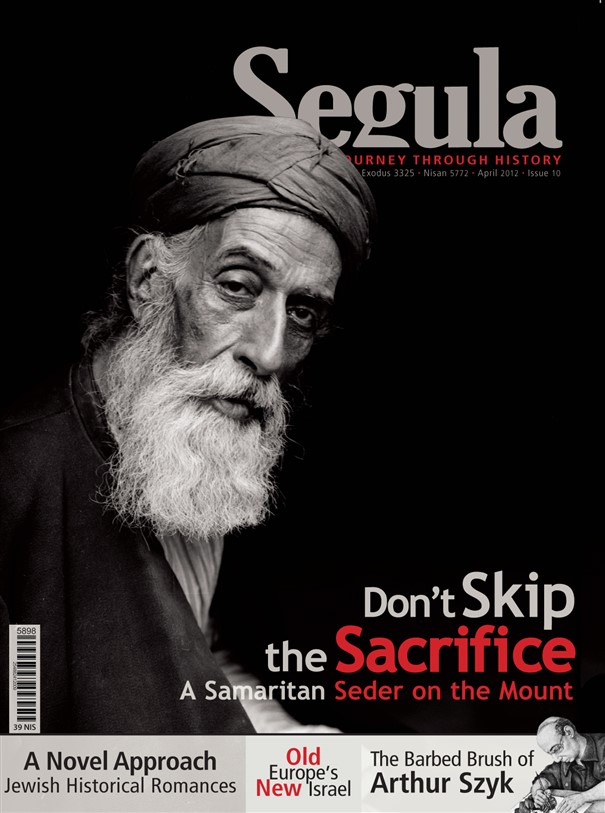

The paschal lambs are bleating on the road to Nablus. The community elders are decked out in white and the final preparations for the sacrifice on Mt. Gerizim are nearing completion. Is this what the Temple Mount is waiting for?

Sitting down at the Seder table today, reciting the Haggada and recalling the paschal sacrifice it describes, do we ever spare a thought for the people who still celebrate Pesach as the Bible describes it? Every year, for two millennia, paschal lambs have been slaughtered on Mt. Gerizim in Samaria. Do the Samaritans fulfill the ideal that Jews have only been dreaming of all that time? At first glance, the Samaritan Passover looks like a fair reconstruction of the original festival celebrated by Jewish pilgrims on the Temple Mount, but bearing in mind the ancient rivalry between the Jewish and Samaritan communities, could the two really be the same?

To answer this question, we have to head up the mountain overlooking Nablus, timing our visit carefully to coincide with a specific day in the month of Nisan.

The day of the paschal sacrifice is central to the Samaritan calendar. It reinforces the links among all members of the community – whether they live in the bustling Israeli city of Holon or on the sacred slopes of Mount Gerizim. Skip the paschal sacrifice just once, and you’ve severed your communal ties for good. There’s no way back.

This is the scenario poignantly depicted in The Lone Samaritan, a recent Israeli documentary that tells the story of Israeli actress Sophie Tzedaka and her father, Baruch, whose four daughters all ultimately left the community (see “Standing Alone,” below). The film, which made quite an impact, winning a number of international awards, illustrates the close-knit relationships binding the members of the Samaritan community on the one hand, and the difficulties facing families whose members fail to conform to its norms, on the other.

Standing Alone

The Samaritan year is divided into two. “Before” is before the paschal sacrifice and belongs to the preceding year; “after” belongs to the new one. In the moment of transition from one year to the next, every Samaritan plumbs the depths of his or her soul and makes a final reckoning of the year just passed: where was I at last year’s paschal sacrifice, and where am I now? A moment after the lambs are slaughtered, everyone crowds around the high priest, kissing his hand and then both his cheeks, in Middle Eastern fashion. Happiness engulfs the entire community.

Yet one man stands apart. A psychological gulf, far wider than the few meters dividing him from the reveling crowd, keeps Baruch Tzedaka away from the rest. His wife stands nearby, close but not too close. She, who knows him best of all, understands that he needs to be alone.

He takes stock of what he used to have and what is his no more. He had a daughter, one of four: beautiful, intelligent, popular, and successful. Famous, even. Then she fell in love with a Jewish boy, converted to Judaism and had to abandon the Samaritan community, snapping a family chain that went back 125 generations. She had a daughter, got divorced. But there was no way back – it was too late. Then, one by one, her three sisters left too, abandoning the religion, the faith, and the rituals. He had had four daughters – and not one had remained in the fold. He knew the meaning of his neighbors’ pitying glances. “It was your upbringing. That’s what did it. It’s your own fault.”

He still feels as though he belongs, but the sense of alienation hurts. The chilliness that even his relatives display bites keenly. He is a stranger among his own people. First he lost his daughters, the lights of his life. Then, in another bitter twist of fate, he lost his eyesight. What remains?

His muted cry of prayer rises fleeting on the wind.

Nothing like a mitzva

The entire ceremony of the paschal sacrifice unfolds in strict accordance with Exodus 12 – in its Samaritan interpretation, that is. On the tenth day of the first month, as the Samaritan calendar calls it – which the Jews would call the tenth of Nisan – communal representatives buy lambs for the sacrifice. This practice is based on Exodus 12:3: “Speak to the entire congregation of Israel, saying, on the tenth day of this month shall they take until them, every man, a lamb, according to the house of their fathers, a lamb for a house.” They inspect the beasts carefully to make sure they are free of defects – flawed livestock are unfit to be sacrificed – and ensure that all are one-year-old males, as prescribed. Each family, or group of families, purchases a lamb and guards it meticulously until the day of the sacrifice: “until the fourteenth day of the same month […] towards evening.” (ibid. 12:6)

At midday on the fourteenth by Samaritan reckoning, the ritual begins. Fires are lit in “paschal ovens” – large pits lined with stones. The fires will burn for several hours, heating the stones so the slaughtered lambs will roast to perfection. Long, wooden rods, hewn from pines growing on the slopes of Mt. Gerizim, have been prepared as skewers. More than fifty lambs are penned nearby, awaiting slaughter. Two or three hours before sunset, the community leaders and elders gather at the home of the High Priest or at the sacred compound on the mountain, mingling with the many guests who have come to put in an appearance, to meet, see and be seen. The Israeli Military Administration and the Palestinian Authority each send a representative, and diplomats, politicians, and municipal figures rub shoulders with anthropologists, academics, and friends of members of the community.

About an hour before sunset, a procession of dignitaries, headed by the high priest, sets out for the sacrificial site. The mass of guests presses against the fences surrounding the sacred compound. Dressed in white from head to toe, the young men of the community gather near the altar, not a raised platform but a trench, in accordance with the Samaritans’ interpretation of Exodus 20:21: “An altar of earth shall you make to Me.” The trench is lined with stones, in fulfillment of the subsequent verse, “And if an altar of stones shall you make to Me…,” and containers of water are positioned nearby for use in cleaning and skinning the sheep. A fire is lit in the trench, and the community elders surround the high priest, chanting a liturgical song. The lyrics, in Aramaic, describe the birth of Isaac and the events of the Akeda, when a ram was sacrificed in his stead.

The paschal ritual about to take place is – in Samaritan tradition – essentially a re-enactment of that sacrifice. The priest mounts a small, stone platform, turns his face toward the setting sun, and begins to recite the verses commanding the people of Israel to perform the paschal sacrifice: “And Sh’meh said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt….” The name of the deity is not pronounced as written; instead, the Samaritans use the Aramaic word sh’meh, “the Name” – not dissimilar to Orthodox Jews’ use of Hashem instead of the tetragrammaton. The priest’s voice crescendos; the entire audience stands riveted. Youths begin dragging the sheep to the slaughter, and the ritual slaughterers unsheathe their knives. As the sun drops below the horizon, the priest proclaims, “and the entire host of the congregation of the Children of Israel shall slaughter it” (Exodus 12:47, Samaritan version).

The climax is reached, the lambs are slaughtered. The crowd erupts in a commotion of hugging and kissing, and the ecstasy of an ancient ritual successfully performed is palpable in the air. The paschal sacrifice, the first commandment given to Israel, the commandment that set the Exodus in motion, has once again taken place.

The Good Samaritan

The New Testament story of the Good Samaritan reflects the tensions between rabbinic Judaism, Christianity, and Samaritanism, which vied with each other in Judea during the first centuries of the Common Era. A wounded man is ignored first by a priest, then by a Levite, but cared for by a Samaritan. Jesus enjoins his disciples to emulate the Samaritan, implicitly rebuking the Jews.

The Bread of Sacrifice

The Feast of Matza begins at sunset, as the fourteenth of the month becomes the fifteenth. Samaritan terminology preserves the biblical distinction (blurred by rabbinic Judaism in the mishnaic/talmudic era) between Pesach, on 14 Nisan, when the paschal sacrifice is offered, and the Feast of Matza, spanning the next seven days.

The bustle surrounding the paschal sacrifice lasts deep into the night. The sacrificial blood is carefully channeled into the trench that serves as the altar, and the slaughterers each smear a drop of the blood on their foreheads, recalling the verse: “And they shall take of the blood and put it on the doorposts and on the lintel of the houses in which they eat it” (ibid., 12:7). This is one commandment the Samaritans do not fulfill literally, perhaps because in the Arab cityof Nablus where they used to live, the mark of blood on their doorposts could have cost them their lives.

The lambs are skinned, their internal organs removed. These are either burned on the altar or washed and returned to the body of the animals.

About two hours after the slaughter, all the lambs are ready for roasting. In a surprising parallel to the tannaitic dispute between Rabbi Akiba and Rabbi Yose the Galilean, some have their organs tucked inside, as Rabbi Yose instructed, while the organs of others are suspended on the skewers, in accordance with Rabbi Akiba’s opinion. Salt is sprinkled liberally, in keeping with “With all your offerings you shall offer salt” (Leviticus 2:13).

A signal is given, and representatives of all the families gather round the ovens, clutching their skewered lambs. Theoretically, each extended family has its own oven, but little attention is paid to which oven is used by whom. Each lamb must be roasted separately though; the skewers are pushed deep into the ground of the roasting pit so that each lamb stands independently, touching neither the sides of the oven nor the other carcasses. Commotion reigns supreme. Everyone, young and old, is busy sealing the ovens: first a metal grille, then a layer of sacking and finally, a coat of moist soil which effectively extinguishes the flames below. The heat roasts the lambs without burning them; any crack allowing smoke to escape is plugged at once.

Watching through the Night

While the lambs are roasting, it’s time for mingling. Outsiders are now allowed to enter the enclosure for a close-up view; questions are asked and answered – a unique opportunity to hear an insider’s take on Samaritan culture and tradition.

By the time the lambs are ready, most of the guests are long gone. Some Samaritans, mostly the young and young at heart, gather near the ovens, chanting festive hymns in Aramaic interspersed with snatches of verses from the Samaritan version of the Torah. Others have gone home for a quick nap while some, especially the youngsters, take the opportunity for some informal matchmaking. All are at their best here, at ease and dressed in their finest.

As midnight approaches, the streets of the Samaritan neighborhood on the upper slopes of Mt. Gerizim come alive. The moment of truth has come – the lambs are ready to be removed from the ovens. Experience has taught the Samaritans how big the oven should be so that the lamb roasts properly in the allotted time without burning. Families using newly-built ovens take a risk: too small, or stoked with too much fuel, and the lamb inside could burn to a cinder and be inedible. To avoid such inauspicious disappointments, most members of the sect prefer the spacious ovens used by previous generations, with their proven, carefully calculated ratio of oven space to fuel.

At midnight, the more muscular members of the community gather round the ovens and, in unison, raise the metal grilles. As the smoke spreads and dissipates, youngsters grasp the skewers and lift the lambs out of the ovens. Roasted to a turn, the meat is placed on platters or trays already arrayed with matza and bitter herbs.

The Samaritan matza resembles a pita and wraps easily around the lamb and bitter herbs to make a sandwich, as described in the Talmud. The matza (salted as part of the sacrifice), the mutton, and the Samaritans’ species of bitter herb – the exceptionally bitter “garden herb” – make for a particularly pungent sandwich.

Break No Bones

“Priests are speedy,” the sages said, and the Samaritan priests prove it by eating the paschal lamb straight from the oven. The rest of the congregation bursts into song, celebrating the completion of another paschal sacrifice.

Some families eat their lamb on the spot, while others go for take-out, eating the meat at home. Some eat standing up, others seated. Some lay the tray of meat on a table; others put it on the ground. All, however, observe two rules meticulously: “You shall eat it hastily” (ibid. 12:11) – they devour the meat as if they were prepared to join the Exodus at any moment. And “You shall break not a single bone of it” (Bamidbar 9:12) – all eat with their hands lest they inadvertently break any bones; forks and knives are nowhere to be found. All members of the sect, without exception, must eat from the sacrifice on this night. Parents prod infants, long since sound asleep, pressing the meat between their lips. Sometimes the youngsters refuse to eat, wailing at their rude awakening. But a commandment is a commandment, so at the very least some meat will be smeared across every child’s mouth, on the assumption that he will “partake” of the sacrifice by licking his lips.

The slowest diners finish well after midnight. Any leftover meat is returned to the altar and burned: “You shall let nothing of it remain until morning; and that which remains …you shall burn with fire” (Exodus 12:10).

The morning service will take place about an hour before dawn, so very few hours of sleep remain. That could be why the pilgrimage to the top of Mt. Gerizim is traditionally deferred until the last day of the Festival of Matza, which the Jews call the seventh day of Pesach.

The Samaritan Stories

-

Cuthites from the Tribe of Benjamin: The origins of the Samaritans are shrouded in the mists of time and controversy

- The Creed of the Holy Mountain

- Similar but Different – the Samaritan Calendar

- Matchmakers’ Night

Remembrance or Reenactment?

There are not a few differences between the Samaritans’ paschal sacrifice and the corresponding Jewish ritual described in the Mishna.

The Samaritans procure their lambs on the tenth of Nisan, as did the Israelites in Egypt in the year of the Exodus. In Jewish tradition, however, after that first celebration of Pesach there was no need to purchase the lamb in advance. Jewish law requires that each lamb be roasted separately over an open flame. The Samaritans, by contrast, roast several lambs together in a sealed oven. Finally – and this is the biggest difference – the main course of the Seder consisted of meat from the standard festival sacrifice, with the paschal mutton served as “dessert,” while the Samaritan banquet centers on the latter.

While the similarities are striking, the differences reveal a subtle shift of emphasis. The Jewish ritual recalls the night of Exodus but does not seek to repeat it. The experiences of thousands of years of exile have been integrated into the story of salvation told in the Haggada. For the Samaritans, however, this night reenacts the birth of the people of Israel. The crux of the evening is not the retelling of an ongoing story – “You shall tell your son” (ibid. 13:8) – but a prescribed series of actions through which the entire community literally consumes and internalizes its history, becoming one with the ancient Hebrews. Reliving, as opposed to retelling. Which is the surest way to ensure continuation, to transmit traditions to the next generation? If numbers are anything to go by, the tiny Samaritan community has chosen wrongly. But in today’s fast-changing world, perhaps only time will tell.