Music Meets the Fields

One foggy morning in 1878, as legend has it, four horseback riders cantered out of Jerusalem. Near the Arab village of Um-Labbes, where they’d hoped to found the first Zionist agricultural settlement, desolation greeted them. Not a single bird chirped – a bad sign, thought Mazurki, the Greek doctor in the group; this was no place for human habitation. Incredibly, the foursome’s leader, Yoel Moshe Salomon, somehow persuaded the birds to return, and soon houses sprang up and children played in fields long fallow. Since then, it seems, music has played an essential part in the Zionist dream.

Growing up in England some twenty years later, Thelma Bentwich (later Yellin) probably never heard this famous anecdote, which was eventually immortalized in song. But in her life too, Zionism and music went hand in hand.

Carmel Court

Thelma’s father, lawyer Herbert Bentwich, seems to have caught the Zionist bug from his illustrious employer, Sir Moses Montefiore. Bentwich hosted Theodor Herzl, Israel Zangwill, and a host of other prominent Zionists at his London home, which later became the Israeli ambassador’s residence. Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president, was a close friend, and Bentwich helped formulate the Balfour Declaration of 1914. Entranced by his first visit to the Holy Land in 1897 but not yet able to emigrate, he dubbed his summer estate in seaside Birchington “Carmel Court.” His daughter and son-in-law, Nina and Nicholas Lange, later gave their Zichron Ya’akov home the same name.

Along with a traditional Jewish upbringing and a lively interest in Zionism, Herbert and his wife, Susannah, were determined to imbue their eleven children with a love of music, especially since their mother was a gifted pianist who had given up her musical career to take care of them. With true British orderliness marred only by the fact that the family fell one short of a dozen, the children were divided into threes and fours. Each group had its own bedroom, nursery, and classroom as well as its part to play in the family orchestra. The eldest in each group usually played piano; the second-oldest, violin; and the third-, cello. As the ninth child, Thelma (born in 1895) therefore became a cellist more or less by default.

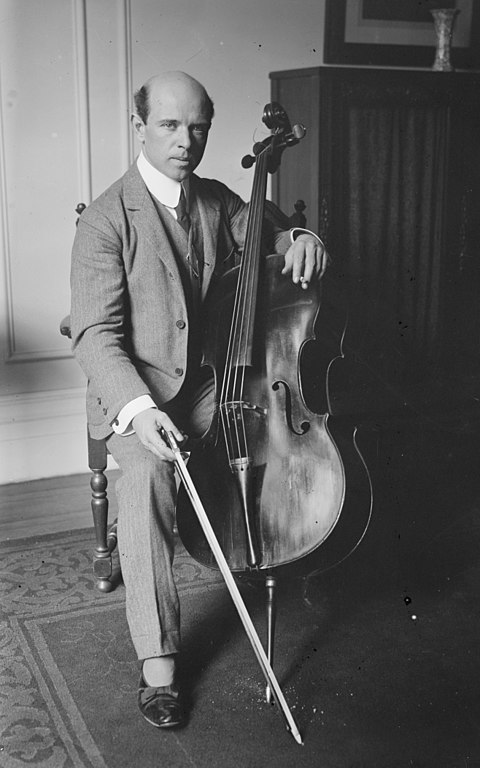

Thelma quickly devoted herself to her unwieldy instrument, and her natural aptitude, hard work, and determination soon made her a sought-after addition to string ensembles. She won a three-year scholarship to the Royal College of Music at age sixteen, studying under the famous Spanish cellist Pablo Casals, who realized her potential. Yellin’s sister recalled a telling exchange between the two musicians. “When [Thelma] once remonstrated against his desire to become a conductor, saying, ‘There is only one cellist like you,’ he told her: ‘And you will then be that one cellist!’ ” (Margery Bentwich, Thelma Yellin – Pioneer Musician [Rubin Mass, 1964], p. 17).

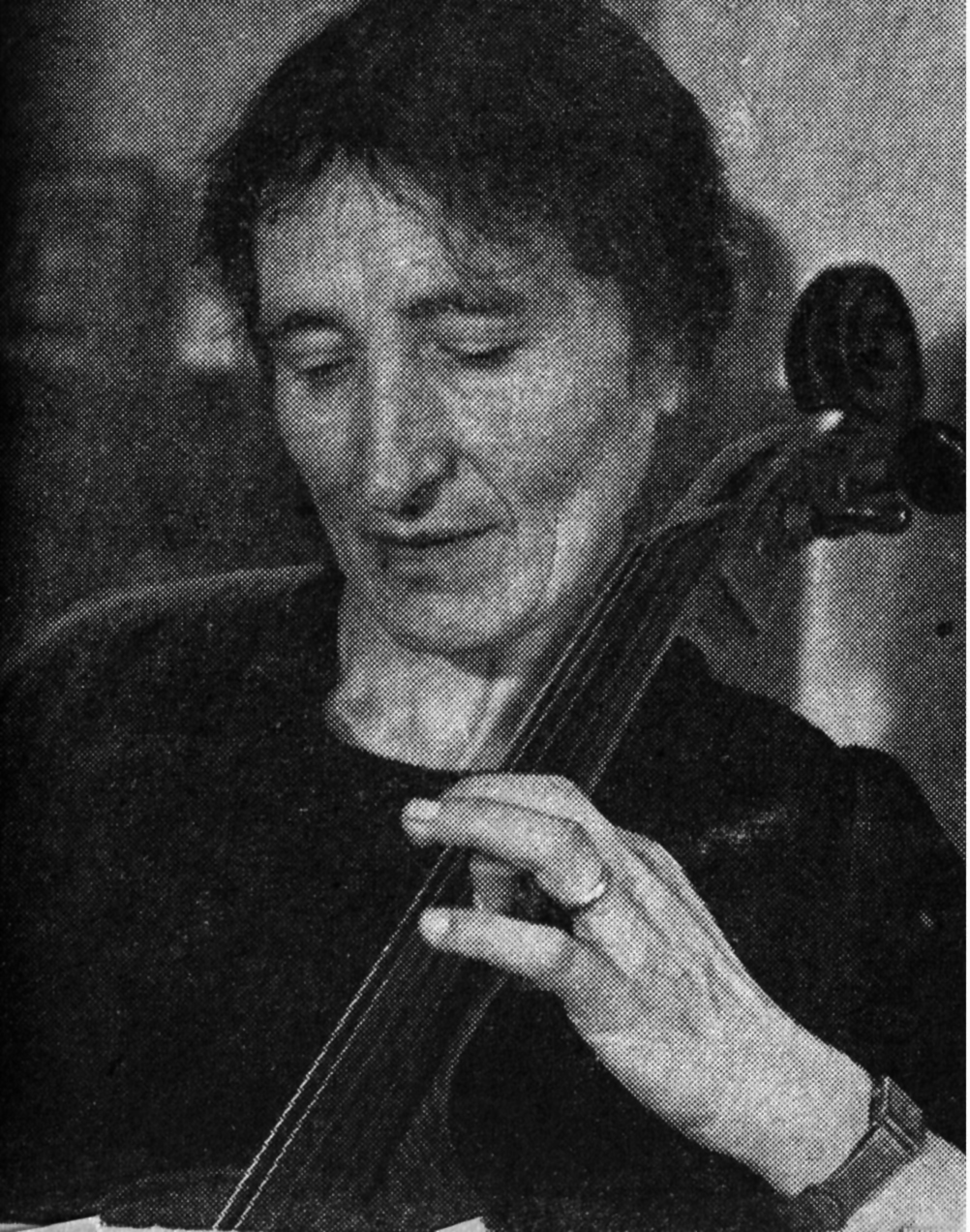

Pablo Casals, Thelma’s mentor, was a revolutionary musician. In 1909 he performed a Bach cello suite without accompaniment, ushering in a new era in cellists’ repertoire. His last concert was in Jerusalem in 1973, two weeks before his death. Casals circa 1910–20

As Thelma grew older, music became her path to spirituality and truth. In early 1914 she wrote in her diary:

For these years are my precious years, and every deed in them matters; and I hate to let them go as if they were of no value. I pray that every day may record some fresh activity, all leading to the great goal – the truth, in music as in all. Let me never feel that the day has gone with no part of a step added to the ladder. The life of man is short, but he can make it long who strives every hour and every day for something beyond himself – the ideal that has no beginning and no end. (ibid., p. 18)

Doubts and Difficulties

Thelma’s music brought her both satisfaction and intense anxiety. Other issues, too, gave rise to soul searching and self-doubt. With the outbreak of World War I, she wondered about devoting herself to superfluities while the world was coming apart at the seams:

October 18. The world gets sadder and ever sadder…. Especially at night the terribleness of it all comes over one like an overwhelming wave…. And my little efforts to achieve something feel so infinitesimally small by the side of the great questions and trials being solved every day that I wonder I could ever see a bigness in them. And yet music is a great and good thing, and in these dreadful times it is a blessing for me to think that I can give of its beauties to others. (ibid., p. 19)

Deciding that at the very least she could share her music’s beauty with the boys at the front, Thelma joined a group of musicians performing for the troops in France. The trip was exhausting but satisfying.

In 1915, Thelma’s mother died suddenly, and the loss affected the entire family. Thelma struggled to live up to her mother’s legacy and remain faithful to both her religion and her music. She coped with the many concerts scheduled on Saturdays by timing her appearances to coincide with the end of the Sabbath. But the tension between her two loves came to a head. Her need for freedom of expression conflicted with the religious restrictions that bound her. In addition, Thelma had fallen for a young medical student and amateur musician whose mother was Christian. After much turmoil, she buried her affections and remained within the fold.

Yet the perfectionism demanded by Thelma’s music took the heaviest toll. The grind of rehearsals, the need to achieve new heights as a performer, the never-ending competition, and stage fright finally culminated in severe physical symptoms. Protracted bouts of pain preceded a nervous breakdown. When her family suggested an overseas breather, she jumped at the idea.

A New Beginning

Mandate Palestine was the obvious destination for Thelma. It was the land of her childhood dreams, and three of her siblings already lived there. Joining her brother Norman, then legal adviser to the British military government in Jerusalem, Thelma soon felt she’d left her worries as well as her symptoms behind. On her second day in Jerusalem, in May 1920, she wrote in her diary:

Jerusalem. An atmosphere of sun and breeze, the air full of the scent of acacias and pines, the roads dusty but full of interest. The German Colony is just like a country village, the population equally divided between English and Arab; also some Indian soldiers. These pray at a little shrine opposite my window. It is an atmosphere for prayer, or at least for taking life peacefully and seriously. I am more at peace than I have ever been, I think. For the first time, the sense of competition has left me, and I am content to be one in the cycle of human lives. (ibid., p. 37)

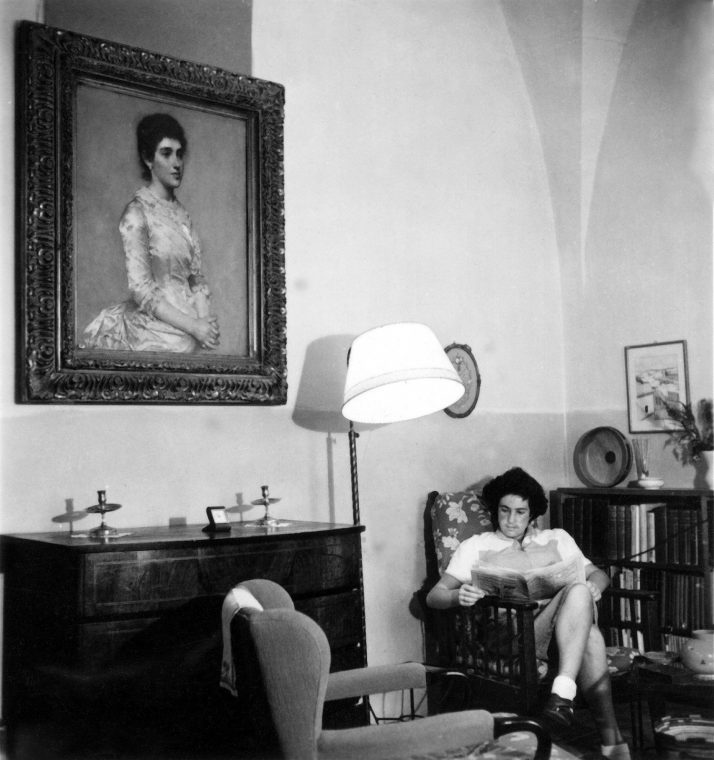

Thelma at home in Jerusalem, beneath her own portrait

Thelma’s pace might have slowed, but even in Jerusalem she pursued her impossible dreams. While improving her Hebrew and mingling with local intellectuals, she kept up with her music and even began performing again. Classical music in Palestine was in its infancy, with Tel Aviv’s Shulamith School of Music (launched by Shulamith Ruppin) and the Jerusalem Music Academy. With enthusiastic support from the British high commissioner, the governor of Jerusalem, and her brother, Thelma founded the Jerusalem Music Society. Appearing in a variety of musical ensembles with her cello – then something of a novelty in the musical landscape – she was soon an integral part of the city’s cultural life.

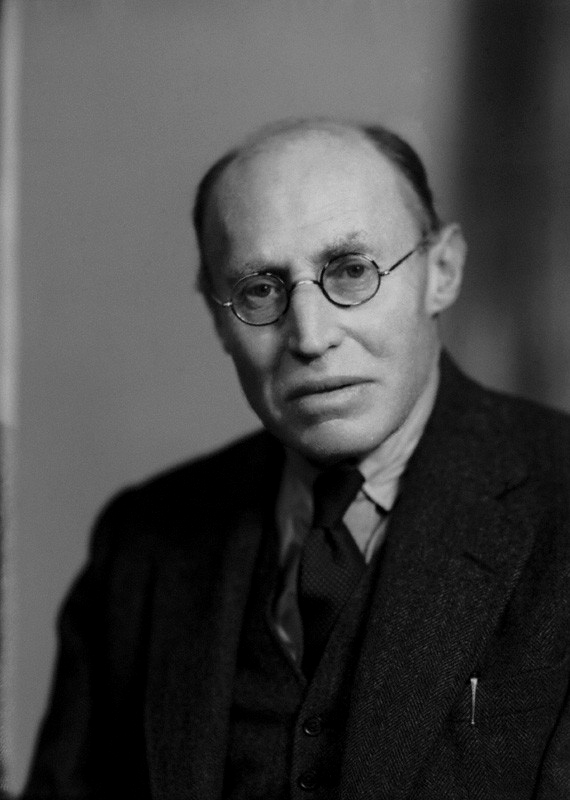

Thelma’s brother Norman Bentwich was an ardent Zionist, although his position in the Mandate government meant that many saw him as an enemy. Only after he’d been injured in an Arab assassination attempt, and fired due to Arab pressure, was his contribution to the Zionist cause more widely appreciated. Bentwich in 1950

Eliezer Yellin, son of the well-known academic David Yellin (who founded one of the first Hebrew-speaking teachers’ seminaries in the country), became a close acquaintance. Eliezer was an architect and engineer, and an unusual combination of East and West, tradition and modern European culture. (His grandfather was Rabbi Yehiel Michel Pines, a leader of the early Zionist movement Hovevei Zion.) Thelma the dreamer and Eliezer the pragmatist complemented each other perfectly, and they were married in March 1921. Despite quickly becoming a mother, Thelma continued organizing concerts and running her musical society. Soon after the birth of her first child, in January 1922, she wrote to her father:

My time has been divided between baby and the Musical Society. The latter is much more troublesome than the former. (ibid., p. 48)

Ram’s Horn and Cello

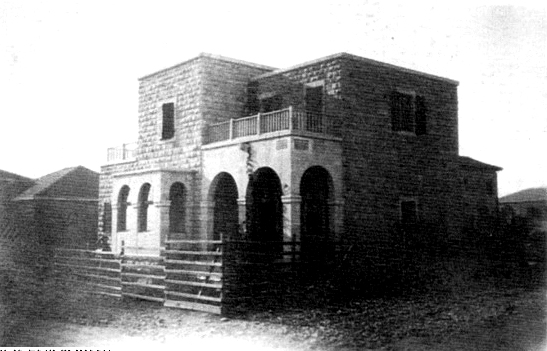

Eliezer and Thelma moved into their first house – one of the first in the Jerusalem garden neighborhood of Rehavia – in 1924. Eliezer’s architectural firm had planned the neighborhood, and the Yellin home soon drew musicians and intellectuals. The first kindergarten in Rehavia was in their house, giving all four Yellin daughters the advantages of early childhood education. The four – Shoshana, Yehudit, Yonah, and Viola – made up Thelma Yellin’s “string quartet,” as she fondly called them.

Thelma Yellin House, 14 Ramban Street, Jerusalem, was the first home in Rehavia when it was completed in 1924

As her daughters grew up, Thelma gave more concerts and went back to touring Europe, performing with some of the biggest names in classical music. Many great musicians arrived in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s, fugitives from the general atmosphere of anti-Semitism or from the Nazi regime in particular. Thelma soon recruited them for her various music projects. Some taught in the school she helped found in Jerusalem in 1933, which eventually became the Jerusalem Music Conservatory. And the string quartet in which she played was privileged to be conducted by Arturo Toscanini when he visited the country in 1936.

These years of musical development were clouded by the precarious security situation in Palestine, with the Arab revolt of 1937 inflicting numerous casualties on Jewish civilians. Among those killed was Thelma’s brother-in-law, Avinoam Yellin, but she insisted that music continue to be played in Jerusalem despite the many tragedies. In a New York Times article entitled “Music in Palestine between the Two World Wars,” she turned a Talmudic saying, “The works of My hands are drowning in the sea, yet you sing?” inside out. “The finest way of meeting tragedy is to transform it into song,” she wrote (Bentwich, p. 72).

World War II brought the Yellin family more grief. Eliezer’s parents passed away one after the other, and he struggled to cope with the loss. Work pressure also compromised his health, and he died just before the war’s end. Heartbroken, Thelma didn’t play for months, but eventually her will to live won out. Her daughters’ care, the marriage of her eldest, and becoming a grandmother all gradually brought joy back into her life, and she returned to music.

In the summer of 1947, the Jewish Agency sent Thelma on her first visit to the United States. As a fervent Zionist and famous musician, she was an ideal choice to boost the image of the Jewish state in the making. Stopping en route in England, she made sure to be in synagogue for Yom Kippur. But her next move showed her just how far she’d moved away from the young woman torn between her music and her faith:

Rushing up from there to Central Hall Westminster, to hear Fournier play the Brahms sonata with Schnabel, I had a strange feeling of dual personality; the music meant more to me than the shofar; in Palestine we certainly get right away – for good or bad – from traditional Judaism. (ibid., p. 89)

Though intoxicated by America’s wide-open vistas and great cities, its vibrant musical events, and its Jewish communities eager to hear her stories of life in the swiftly developing homeland, Thelma was concerned with what was going on inside the United Nations, not far from her speaking engagements. After the UN voted on November 29, 1947, to create a Jewish state in Palestine, she wrote:

3 December ’47. I feel as if I were suspended between New York and Jerusalem, wondering what tomorrow will bring. A new volume of history is being written; one would like to be able to read its last page! I was present at the prologue. (ibid., p. 92)

Soon after the State of Israel was established, Thelma arrived back home. Until her death in March 1959, just before her sixty-fourth birthday, she kept up her concert appearances and created a variety of musical institutions. Her last such initiative was a high school for music students, allowing talented young musicians to matriculate while dedicating most of their time to their art. The Thelma Yellin High School of the Arts opened shortly after her death. The woman who’d resigned herself thirty years earlier to being just another cog in the vast wheel of humanity had in fact realized not a few of her most ambitious dreams, leaving her own indelible mark on the homeland she’d built and loved.