Jew Denounces His People to the Czar – in Yiddish

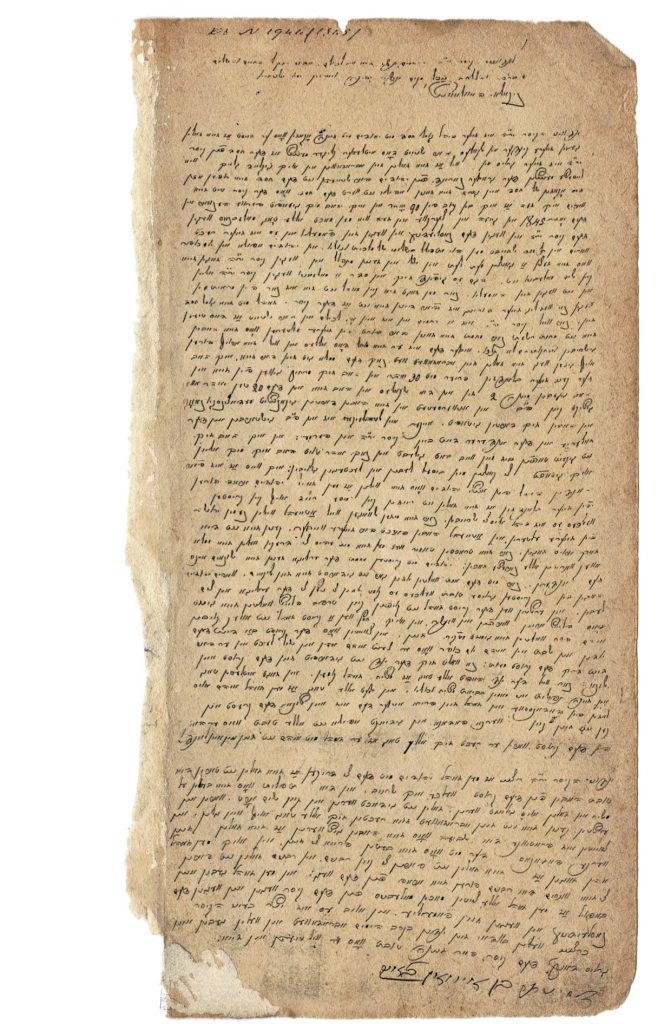

The letter below, sent to Czar Nicholas I of Russia in January 1845 by one Moses son of Isaac Blank, touched off something of a storm when it was uncovered in the 1990s in Soviet archives after the Iron Curtain lifted. The reason was the identity of the writer, a Jew from Zhitomir who had converted to Christianity and whose great-grandson was none other than Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (originally Ulyanov), founder of the Soviet Union. Despite having adopted the Russian name Dmitry Ivanovich, Blank (the law required him to keep his last name) wrote his letter in Yiddish. It was filed by the head of the Russian secret police, along with a Russian translation, in the czar’s personal bureau.

Moses Blank seems to have quarreled frequently with his community well before his conversion. In 1809, after a string of disputes, his fellow Jews accused him of setting fire to his hometown of Stari Konstantinov (Old Konstantin), in Volhynia province. The court found him innocent, but he moved to nearby Zhitomir, from which he sent a letter of complaint about his former neighbors to Czar Alexander I. This letter got no farther than the local authorities in Zhitomir. Between 1838 and 1844, Blank lost most of his property, including a brickmaking factory, in another bitter legal battle, this time with the Zhitomir Jewish community. He converted to Christianity immediately afterward. Almost his first act as a Christian was to send a letter denouncing not only the Jews of Zhitomir, but Russian Jewry altogether. Its repercussions would affect the country’s Jews for years.

May God Bless and Keep the Czar

To our lord, His Majesty the czar, be his mercy extolled, may God grant him life and peace, blessing and success wherever he turns, … Nikolai Pavlovich:

Our lord, His Majesty the czar, showed the Jews great kindness by ordering them to enroll their children in government schools [this same czar conscripted Jewish boys into decades of military service!]. While the wise understand that the czar, in his abundant kindness, wants the Jews to be educated and to dress in the manner of decent people, fools among the Jews do not appreciate this kindness. They term these benevolent orders a “decree.” They are unworthy of the czar’s kindness.

I am nearly ninety years old and was baptized into the Church on January 1, 1845. Attending services, I see how prayers are said every day for the well-being of his Majesty the czar, the crown prince, and his family. This is as it should be, for the Talmud states, “Pray for the well-being of the government.” But the Jews utter nary a prayer for the government, even on Yom Kippur, when they sit in synagogue all day. … Although a prayer for the well-being of His Majesty the czar (albeit not for his family) does appear in the prayer book, the Jews never say it….

I enrolled my two sons in [government] schools and sent them to the university in [St.] Petersburg twenty years ago, where they studied medicine and were baptized. One of them, a military physician, died in [St.] Petersburg of cholera; the other [Lenin’s grandfather] is serving the czar in Perm.

I could not be baptized as long as my wife was alive, but after her death I, too, was baptized so that I could live out my days in the true faith. I know that many Jews wish to disabuse their coreligionists of their obtuse ways … but cannot speak out because they wish to inherit their parents’ estates or are afraid of their wives….

It is my wish that the Jews not be allowed to benefit from Christians … and that their prayers for the Messiah be deleted…. Second, they cannot be loyal citizens (as they have vowed) while praying to be “liberated.” Furthermore, they should be ordered not to travel to their rabbis, and their rabbis should not visit them, as [rabbinic] influence leads them astray. Finally, they should be ordered to pray for the well-being of the czar, the crown prince, and his family.

Thus, if the czar wills it, the Jews will find enlightenment and thank him effusively for the benefits he wishes to bestow upon them.

Dmitry Ivanovich Blank

January 5, 1845

Two days after the head of the secret police read Blank’s letter, he presented Nicholas I with a report specifying the author’s allegations against the Jews and proposing appropriate measures. Near the end of the report, the governor of Zhitomir dismissed Blank as an inveterate, accusative troublemaker. Nevertheless, when Blank wrote again in Yiddish in August 1846, suggesting how best to Christianize the Jews and recommending that gatherings of Hasidim (“well-known zealots”) be banned, his paper was forwarded to the Commissariat for Jewish Affairs. Four months later, the commissariat issued an order via the Ministry of the Interior to monitor recitation of the prayer for the czar and punish those who omitted it. Negotiations on the wording of the prayer continued for ten years.

Converting in Numbers

Until 1990, information on Jewish converts to Christianity in 19th-century Russia was scarce. Nonetheless, after extensive research, Prof. Michael Stanislavsky claimed that some thirty thousand Jews converted under Nicholas I – at least five thousand of them of their own free will. Basing himself largely on literature and the scant documentation available to him, Stanislavsky enumerated five categories of converts: those who sought educational or professional advancement, the upper echelons of the petty bourgeoisie, criminals, sincere believers, and those who saw no other way to escape the abject poverty in which the majority of Jews lived. Most converts, he believes, belonged in the last category.

The church archives, population statistics, police records, and other documentation that came to light in 1990 as a result of glasnost reveal another category of converts – informers. Some wanted revenge after a neighborly disagreement or – as in Blank’s case – a communal dispute. Roughly one thousand secret police files from the rule of Czar Nicholas (1825–55) pertain to Jews, and many contain informers’ reports and the results of subsequent investigations. Research copies are available at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People.