New and exciting research has now been published on the DNA and mitochondrial makeup of the Dead Sea Scrolls – with some surprising results

An international interdisciplinary research team has successfully developed new ways to analyze and identify ancient DNA taken from the animal-skin parchment on which the Dead Sea Scrolls were written. Unique genetic fingerprints allow fragments to be organized into groups, showing which scroll fragments came from the same animal and thus whether those previously attributed to the same scroll are indeed connected.

Tel Aviv University and Israel Antiquities Authority researchers with scroll fragments

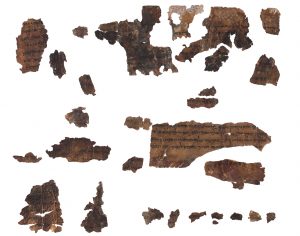

Fragmentary Evidence

The twenty-five thousand fragments of parchment and papyrus making up the collection of one thousand scrolls discovered in the Judean Desert have surfaced gradually since 1947, mostly in the Qumran caves on the north coast of the Dead Sea. More were found in other desert locations such as the Murba’at and Tze’elim stream-valleys, and at Masada. They include the oldest known copies of the biblical books, as well sectarian texts belonging to the Qumran community and fragments of other volumes which were excluded from the biblical canon as we know it today. Ever since, archaeologists have been hotly debating whether all these texts were written by the isolationist Dead Sea sect, or whether some were brought into the desert by fugitives from the Great Revolt of 66-72 CE and hidden in caves for safekeeping.

The answer to another fascinating question may lie in the objective criteria by which the various scrolls and fragments – especially those containing biblical texts – can now be grouped. The version of the text appearing in some scrolls differs, sometimes significantly, from the biblical verses of the accepted (Massoritic) text. Does this imply that less emphasis was placed on the actual words of the bible, and more on their meaning, in Second Temple times than in later periods? Or do the different versions reflect the literature of a number of different Judean Judaic sects (such as the Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes mentioned by Josephus)?

Seven Years’ Labor

The research project took seven years to complete. The team was headed by Tel Aviv University’s Life Sciences Professor Oded Rechavi, Prof. Noam Mizrahi from its biblical studies faculty, and Prof. Mattias Jakobsson from Uppsala University in Sweden. Israel Antiquities Authority staff and Cornell University were also involved.

DNA analysis of miniscule scrapings – and even dust particles – from the parchment on which the Dead Sea Scrolls were written allowed researchers to puzzle out the genetic relationship between the animals from whose skin the raw materials were made. Fragments shown to be genetically close are generally considered to have originated from the same locale in Israel – not necessarily Qumran. It emerged that all the sectarian scrolls from Qumran are indeed genetically connected, while they’re genetically distinct from other fragments written in a different style though deposited in the same cave. This would seem to suggest that the genetically variant fragments were brought to Qumran from other parts of the country, and represent the views and beliefs of a wide range of communities in Judea between the last two centuries BCE and the first century CE.

Many Jeremiahs?

This method of grouping the scroll fragments can have far reaching results. Among the surprises gleaned from this research was the discovery that two of the scroll fragments were written on cow-skin, as opposed to the sheep skin generally used for parchment produced in the parched Dead Sea environs. As Professor Rechavi explained:

Two samples were discovered to be made of cow hide, and these happen to belong to two different fragments taken from the Book of Jeremiah. One of these was previously attributed to the same scroll as another fragment that we’ve now found to be made of sheepskin. The mismatch officially refutes this attribution.

What’s more: Cow husbandry requires grass and water, so it is very likely that cow hide was not processed in the desert but was brought to the Qumran caves from elsewhere. This finding bears crucial significance, because the cow hide fragments came from two different copies of the Book of Jeremiah, reflecting different versions of the book, which stray from the biblical text as we know it today.

This would seem to imply that the text of biblical books was once more fluid in style as well as spelling variants than has been supposed. The books of the prophets, certainly, show less insistence on a unified text. It was the message, apparently, that mattered most.