Re-examination of the Samaria Ostracha yields new information on who could read and write in ancient Judea

The question of literacy in ancient (biblical) Israel is crucial for biblical exegesis and related fields. Ancient inscriptions can not only shed light on past events and affirm biblical accounts, but can also tell us about literacy and education in antiquity.

An innovative study developed an algorithm which was used to investigate the Samaria ostraca (ink inscriptions on clay shards). The researchers who developed the algorithm and re-examined the ostraca concluded that only two scribes recorded the deliveries of wine and oil arriving in Samaria in the early 8th century BCE.

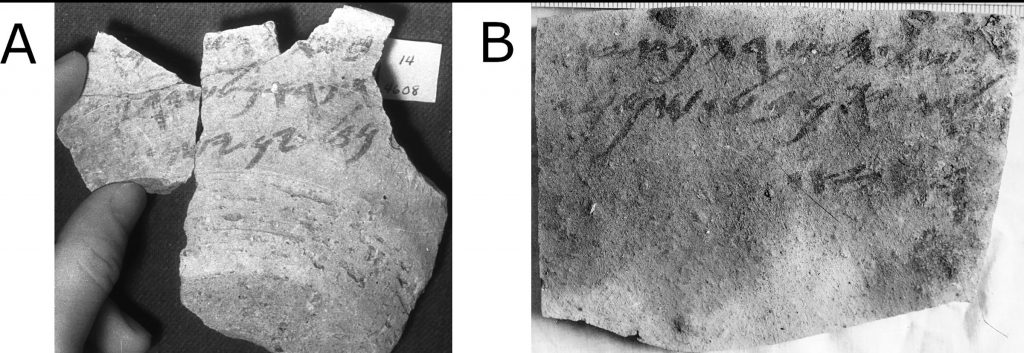

The Samaria ostraca are 109 pottery shards on which royal scribes recorded the amounts of oil and wine brought to the royal treasury of King Jerobam II in the first half of the 8th century BCE. Most of the ostraca were excavated by the Harvard University expedition of 1910 (several more were found during the 1930s). These inscriptions, written in paleo-Hebrew in ink on clay, are very significant both for research into the history of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, and for our understanding of how literacy spread in this early stage of ancient Israel’s history. They are also crucial for the linguistic study of the Northern Israel dialect, of which even to this date very little is known .

The study was led by a team of scholars from Tel-Aviv University, including Drs. Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, Arie Shaus, and Prof. Eli Turkel of the Department of Applied Mathematics; Prof. Eli Piasetzky of the School of Physics and Astronomy, and Prof. Israel Finkelstein of the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations.

The study established that these inscriptions were most likely written by only two scribes, based on a method combining image processing and newly developed statistical learning techniques. This outcome contrasts with previous results, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judeah a century and a half to two centuries later, ca. 600 BCE. In other words, it seems few people could read or write in the countryside, and only scribes or educated officials surrounding the king’s court were able to do so fluently.

In a recent article, this team of scholars dealt with the corpus of similar ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad in Judah (the southern of the two Hebrew kingdoms), dated to ca. 600 BCE. This time the algorithm allowed them to estimate that the 18 inscriptions investigated were authored by at least four individuals. In other words, 150 years before the time of the Arad ostraca, only a few officials and educated individuals had mastered writing. This level of literacy around the king’s court may have also allowed the development of prophetic writings such as the books of Jeroboam’s contemporaries, Hosea and Amos.

King Jerobam II (“The Great”, son of Jehoash), reigned for 41 years in Samaria, and is considered one of the greatest kings of Israel. He is mentioned briefly in II Kings 14: “He was the one who restored the boundaries of Israel from Lebo Hamath to the Dead Sea… [and] he recovered for Israel both Damascus and Hamath, which had belonged to Judah…“. The Samaria ostraca are the only remaining fragment we have of the reign of this great king.