This article was published in issue 53 | Av 5780 | July 2020

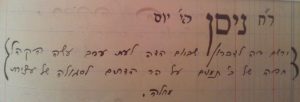

On the first day of Nisan, 1909, a Jerusalem burial society made the following entry in its log:

Let it be noted for posterity that on this day, toward evening, the congregation raised a wedding canopy over two Yemenites on the Mount of Olives, as a means of ending sickness. [Hebrew]

Photographed by members of the American Colony Hotel in Jerusalem, this picture of the black wedding held in the Mount of Olives cemetery on the first of Nisan, 1909 is a rare record of such nuptials Photo: American Colony, Library of Congress Collection

Photographers from the city’s missionary American Colony caught the moment on film, and two days later, the wedding was reported in Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s daily paper, Ha-zvi (The Gazelle), with more than a touch of irony:

Don’t think there’s any dearth of highly effective superstitions in Jerusalem, for some loyal agents have finally been found to see to the city’s health and wealth. Today, on the first day of Nisan, one hour after noon, the cure was concocted […]. A lengthy procession stretched all the way from the gate almost to Absalom’s Pillar. When I turned toward the Mount of Olives, the entire slope above the Cave of Zechariah and Absalom’s Pillar was covered by a mass of people. The procession joyously sang its way to the Mount of Olives. Despite a slight, pleasant breeze blowing from the east, the heat was stifling.

Among the Jewish throngs that spilled heavily and lazily over the crest of the hill, amid the weathered graves were English, American, and German representatives. What were the consuls doing here? Nothing less than spectators, watching the Jews’ strange goings-on.

And truly, is there anything more ridiculous than this spectacle? A great crowd assembles on the Mount of Olives to watch the wedding of an orphan bride and her orphan groom, that the merit of their match might end the city’s terrible plague. (Ha-Zvi, 3 Nisan/March 25, 1909)

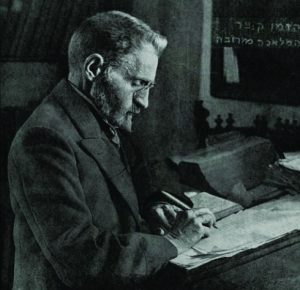

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda considered himself a beacon of Jewish Enlightenment amid the dark ignorance of Jerusalem’s Orthodox community, and he delighted in sharpening his journalist’s pen at its expense

What brought the lively wedding of two young orphans to the somber, grave-lined slopes of the Mount of Olives? Had the wedding halls all shut down? Was this a selfless act of charity on behalf of a destitute couple without family, or was it a superstitious hope that the good deed of the living and the joy of the ceremony would stop the plague raging through the city? Did anyone really believe that the dead lying in the graveyard would intercede on behalf of the living? Or was it more of a preemptive declaration of victory by the surviving children of plague victims, who’d beaten the odds and reached child-bearing age?

The framed entry in the burial ledger of Jerusalem’s Perushim congregation pertains to the wedding of orphans in Nisan of 1909, noting that the ceremony was intended as a charm to ward off plague Courtesy of the Perushim burial society

The framed entry in the burial ledger of Jerusalem’s Perushim congregation pertains to the wedding of orphans in Nisan of 1909, noting that the ceremony was intended as a charm to ward off plague Courtesy of the Perushim burial societyCanopy of Black

Jewish sources have a special term for a wedding ceremony joining two orphans in a graveyard: a “black wedding,” or “plague wedding.” This practice was thought to magically remedy plagues and other tragedies. Nor was it invented in Jerusalem; Eastern European immigrants brought it to the holy city in the 19th century. In his Be’erot Mayim (Wells of Water), Rabbi Zvi Hirsch of Rymanów recounted such a ritual, held in his hometown in 1831:

Cholera, woe unto us, rested upon the land that year, and they performed the well-known good-luck charm of marrying off a pauper to a destitute virgin. They erected the wedding canopy in the graveyard, and when they went to lead the bride and groom beneath the canopy, the bride was afflicted with that plague. [… ] They told our teacher, the holy rabbi Zvi HaKohen, may his memory be a blessing for the world to come, who spoke with his holy mouth, saying: “We have a tradition that the corpse should pass before the bride.” At once, she was cured of her sickness, her strength restored. (Zvi Friedhaber, “Plague Weddings in Hebrew Literature and Newspapers,” Dappim Research in Literature, vol. 7 [Haifa University, 1990], p. 306 [Hebrew])

A similar ceremony was conducted in Zambrów, Poland, in 1893, and described by Meyer Zukeravitz. After all efforts to drive out the plague of cholera had failed, he wrote:

Not yet despairing of God’s salvation, the people tried a third method – the wedding of an orphan bride. There was a crippled virgin in town named Hanna Yente, who was also an orphan, and a stammering beggar who was still single and slept at night on a hard bench in the hostel. The town’s burghers made a match between the two, and the couple agreed.

It was decided that the wedding would be held in public at the community’s expense, in the graveyard. […] The couple was led to the wedding canopy with drums and dancing, and everyone in town – Christians included – came out to rejoice with the bride and groom.

The merit of rejoicing in a good deed stood us in good stead. God saw our affliction and regretted the evil He’d brought on His people, and the plague came to an end. (Shmuel Glick, Light Shone upon Them: Connections between Wedding and Mourning Customs in Jewish Tradition [Efrat: Keren Ori, 1997] p. 175 [Hebrew])

Stain of Superstition

By the early 20th century, the custom was renowned and even quite common. “Plague Weddings in Ashkenazic Tradition,” an article by Dr. Yom Tov Levinsky, characterizes it as a European folk tradition and cites weddings held in Lomza, Poland, in 1906, in Krakow in 1918, and in Siedlce between 1917 and 1925, all to combat plagues and famine. Rabbi Avraham Hershovitz testified in 1918:

Whenever there was plague in the city, a wedding was arranged between a poor orphan boy and girl and held in a cemetery as a good-luck charm; or they would go to bury worn-out holy books containing God’s name, accompanied by a festive crowd all the way to the graveyard, where [the books] were consigned to the ground. (Rabbi Avraham Hershovitz, Compendium of Customs of Jeshurun [St. Louis, 1918], ch. 42 [Hebrew])

Jewish Enlightenment periodicals devoted significant space to the phenomenon, with the editor of Ha-melitz (The Advocate) championing its demise in no uncertain terms. Upon hearing of “black weddings” in Kishinev (today Chișinău, Moldova) he stridently expressed his opposition:

May God’s blessings rest on the heads of those engaged in the good deed of marrying off a poor bride. In its merit, may God halt the avenging angel and turn aside this terrible death from them and from all the towns of our land.

Yet we cannot help but rebuke them if the rumor that has reached our ears is true, that they behaved foolishly and brutishly by holding fifteen [!] weddings in the graveyard. It’s an abomination in Israel, even if a saint – or all the saints, in our country and abroad – decreed this ignorant [practice]. (Ha-melitz, 28 Av/August 9, 1866 [Hebrew])

Shmuel Yosef Finn of Lithuania, editor of Ha-Carmel, wrote similarly. Criticizing weddings held in Ekaterinoslav (today Dnipro, Ukraine), Grodno (in Belarus), and Bialystok (Poland) in the autumn of 1866, he scathingly described one he’d actually attended:

The dread disease [cholera] was first seen in our town a few weeks ago and has claimed many victims […]. One day a group of people decided to stop the plague and end the sickness, so they took a young man and woman from among the poorest and most despised classes and led them with drums and dances to the House of the Living [a euphemism for a cemetery], where they married them off, eating and drinking until they were utterly drunk and claiming this was a surefire cure for cholera.

My heart sank at the sight, and shame enveloped me. I’d never imagined that in this day and age, our Jewish brethren still believed in such bizarre things. When I asked what was going on, what their strange behavior meant, and how they’d come to such an ignorant custom, they laughed heartily and shook their heads at me, saying it was a tradition from their fathers, who must have known what they were doing. It never occurred to these people that not every time-honored tradition is a good one and that some customs are just folly and superstition. (Ha-Carmel, 3 Elul, 1866)

Vain Hope

The last “plague wedding” in Europe was probably the one held in the Żelechów ghetto in 1942 in the hope of halting a typhus epidemic that had already killed hundreds. Representatives of the community led the couple to the wedding canopy in the graveyard just as tradition demanded, followed by refreshments and music in the Judenradt (Jewish Council) building.

Black weddings were common during the Holocaust, but there was no need for a cemetery; the ghettos themselves were graveyard enough. Rabbi Moshe Haim Lau, father of emeritus Israeli chief rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau, expressed exactly this sentiment in a spine-tingling sermon delivered at a wedding held in his home in the Piotrków Trybunalski ghetto. Pointing out that the Jewish nation was currently in the throes of the greatest plague in world history, he prayed:

Our Father who art in heaven, in the merit of this young couple standing today beneath the wedding canopy, cancel the evil decree. Enough! Let the plague that has wiped out hundreds of thousands within Israel – men, women and children – be halted. Send us salvation and redemption from this bitter exile. (Yaakov Kortz, Testimonial: Impressions of a Jewish Survivor of the Nazi Hell in Poland, p. 308 [Hebrew])

Vain hope of relief. Wedding held in the Żelechów ghetto graveyard in 1942

Vain hope of relief. Wedding held in the Żelechów ghetto graveyard in 1942

Graveyard Hullabaloo

Graveyard weddings of orphans were so common that they even appear in Hebrew literature. In Fishke the Lame (1869), Mendele Moykher-Sforim (the pen name of Yiddish author Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh) was among the first to document the phenomenon:

Whoever has yet to see a wedding spring up among the tombstones has never seen a real wedding in his life. They’d feast and drink, dancing before the bride, calling, “Beautiful and pious bride!” – not to make the cholera desire her, as some would say; no, far be it! Rather, to make her doltish husband love her. (Mendele Moykher-Sforim, Tales of Mendele the Book Peddler: Fishke the Lame / Benjamin the Third)

The more common black weddings became, the more violently the Jewish Enlightenment intelligentsia opposed them. Mendele Moykher-Seforim’s biting humor made him one of their most effective critics

Hebrew author Yosef Hayim Brenner depicted a plague wedding in his novel Between the Waters (1910), his first work written in Ottoman Palestine (see “Crashing the Wedding,” pp. XX). And in 1913, S. Y. Agnon published a short story called “The Black Wedding” in the Odessa-based Hebrew periodical Ha-Shiloah. Agnon repeated the motif in his novel Only Yesterday (1946).

Joy in Jaffa

Jerusalem wasn’t the only place in Israel to hold weddings in cemeteries. Shifra Horn’s book Tamara Walks on Water (2004) describes one in Jaffa, based on the author’s research of such an event as cholera ravaged the town in 1902. Originating in Egypt, the plague struck Ottoman Palestine primarily in its coastal cities. Jaffa was sealed off by a government curfew, and burials in the local graveyard, situated in a residential area, were forbidden for fear of spreading infection. Plague victims had to be interred in a new cemetery beyond the population center. As Dov Frumkin’s Hebrew periodical Habazeleth (Lily) reported:

When the plague began to give the angel of death a foothold, the Health Committee appointed by the government to deal with the city’s sanitation ordered that victims of this disease, whatever their faith, be buried not in the ancient cemeteries – most of them close to town – but in a special graveyard designated by the authorities some distance from the city. (Habazeleth, 28 Heshvan/November 28, 1902)

Shimon Rokah, a leader of Jaffa’s Jewish community, received permission from the authorities to purchase a twelve-dunam plot of government land for the new graveyard. The price – in silver medjidie – was paid by the United Ashkenazic and Sephardic Congregations in Jaffa. The site eventually became Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery, resting place of many early Zionist leaders.

The first grave was dug on 10 Heshvan in 1902. A second grave was prepared immediately afterward, at a respectable distance, firmly establishing the land’s new purpose before the authorities could change their minds and demand the plot’s return. (With the mass exodus of Jews from Russia following the pogroms of the 1880s, Ottoman legislation in the last two decades of the 19th century aimed to block Jewish immigration to the land of Israel. As of 1892, Jewish land purchases were also officially outlawed, so this 1902 exception was particularly charged.)

That same day, in the hope of invoking God’s mercy to prevent further infections, two orphan couples were married on the newly consecrated grounds. Two sisters – Snir and Ziona Balisch – wed Moshe Galzan and Yihye Rianni. Habazeleth’s sympathetic coverage of the event – unique among journals of the time – reflected the sentiments of its founder and readers, Rabbi Israel Beck and the pietistic Orthodox community of Jerusalem.

The first two graves in what later became Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery. Two weddings of orphan couples were held there on the day these two graves were dug, at the height of a cholera epidemic

The first two graves in what later became Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery. Two weddings of orphan couples were held there on the day these two graves were dug, at the height of a cholera epidemicThe first two graves in what later became Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery. Two weddings of orphan couples were held there on the day these two graves were dug, at the height of a cholera epidemicThe first two graves in what later became Tel Aviv’s Trumpeldor Cemetery. Two weddings of orphan couples were held there on the day these two graves were dug, at the height of a cholera epidemic

Made for Plagues

Within the land of Israel, Jerusalem was the traditional site of plague weddings – partly because of the city’s dire sanitary conditions. With contaminated drinking water, overcrowding, and sewage flowing alongside streets heaped with refuse, Jerusalem was fertile ground for epidemics. The worst was the cholera outbreak of October 1865. Five hundred died within two months, and the Hebrew letters designating the year (5626) were rearranged to spell “year of the reaper.” Almost every day, the local Hebrew press featured obituaries of community leaders who’d succumbed to the plague.

Yet there’s only one reference to the ritual in the periodicals of 1865, in an issue of Ha-Levanon dated 25 Iyar. Describing a ceremony that took place two weeks earlier, the author protests a custom that unites orphans for life regardless of whether they’re suitable – or willing. The pair in question quarreled after the ceremony; the bride’s mother had driven the groom to distraction, and he’d decided to drown himself in the mikve. Miraculously, some women who’d come to immerse found him in time.

Memoirs of life in Jerusalem in the late 19th century mention other plague weddings staged in 1865. For example, Eliyahu Perosh wrote:

In 5626 (1865–6) there was a particularly severe attack of cholera in Jerusalem, and a wedding was held for a bride and groom in the cemetery on the Mount of Olives as a mystical means of stopping the plague. It was Reb Yosef Lucyner (Danker) and his wife who were married, and the ceremony was conducted in public and with great festivity. (Early Memories: Recollections of Life in the Jewish Community of Jerusalem in the Old City and Beyond in the Previous Century, p. 39 [Hebrew])

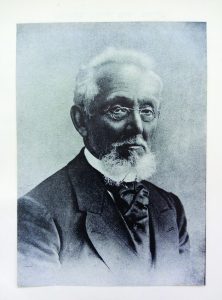

Pinhas Zvi Grayevsḳi, who died in 1941, published a photo album of native Jewish Jerusalemites. Beneath one picture, on page 59, the caption reads:

Rabbi Yosef son of Eliyahu Danker of Lucyn [Ludza, Latvia]. Born in Jerusalem in 5608 (1848) and died there on 6 Nisan 5687 (1927). Guardian of the graves of the righteous and beadle for the burial of sacred papers (geniza).

Probably the same Yosef, this fellow would have been around eighteen when he was married among the tombstones. An 1866 census commissioned by Moses Montefiore lists one Yosef son of Eliyahu Yehoshua, age eighteen, born in Jerusalem, married to Hana, and supported by his father, who came from Lucyn. This documentation too points to Yosef as the groom of Jerusalem’s black wedding of 1865, though he was certainly not an orphan. Perhaps Hana was the unfortunate one, or possibly neither of them had lost their parents – Perush didn’t actually identify bride and groom as orphans.

To Life!

Against this historical backdrop, we return to the wedding with which we began.

In 1909, a meningitis outbreak in Jerusalem claimed many lives, particularly among Ashkenazim. As doctors struggled to diagnose the disease, locals dubbed it “the stiff-necked sickness” – combining its most obvious symptom with the biblical epithet for Israel’s stubborn sinfulness. The city’s Yemenite population (most of which had arrived in 1881) also suffered; 75 percent of the Yemenite children born in Jerusalem perished. Desperate to understand how they’d incurred such divine punishment, the Yemenites consulted the Ashkenazic leadership, which saw only one antidote to the misfortunes of both communities: two Yemenite orphans would marry on the Mount of Olives, in a ceremony organized by the Ashkenazim.

Lavish and well-attended, this plague wedding was probably the most famous, with coverage in the press and in books. Two images of the event have survived, one captured by photographers of the American Colony in Jerusalem, the other by ophthalmologist Dr. Moshe Erlanger. These pictures show the precise site – northeast of Absalom’s Pillar. The photographers kept their distance, however, so the couple isn’t really visible, and there’s no record of the bride’s and groom’s names. The burial society ledger notes that both were Yemenites, though Eliezer Ben-Yehuda wrote that the bride was from Aleppo, Syria.

Ben-Yehuda also described how the groom ran off in mid-ceremony, having not received the cash he’d been promised. Society officials promptly dragged him back and paid up, lest the plague return. The journalist may have exaggerated, but this account certainly reflects his contempt for both the superstitious proceedings and their organizers.

Amid constant death and disease – Ben-Yehuda himself lost his first wife and several children to epidemics – the Mount of Olives naturally became central to community life. Not just a burial site, this “House of the Living” was where individuals came to pray and find solace, and where the entire congregation gathered in times of trouble. Instead of huddling alone in their homes, stricken by sickness and fear alike, Jerusalemites climbed the mount and took comfort in each other’s company, singing, dancing, and rejoicing in fulfilling God’s commands of charity and kindness. Here among the tombstones, they looked death in the face and prevailed.

And here orphans stood alone, bereft of parents to lead them to the wedding canopy, and declared: “To life!” Though the occasion couldn’t have been easy for them, or for their remaining relatives, for the community the ceremony was the ultimate defiance of death. It was a victory for life – and for Jewish national survival.

Did the wedding Ben-Yehuda attended actually halt the plague? The end of his article hints at the answer. Inquiring about the point of the whole to-do, he was told:

Some say it works wonders. “I haven’t lost anything by it, and if it doesn’t help, it certainly won’t hurt. In any case, is it not a great merit to marry off two orphans, and by virtue of the good deed itself, should the Holy One, Blessed Be He, not have mercy?” (Ha-zvi, 3 Nisan/March 25, 1909 [Hebrew])

The author retorts:

But the fact that [the action] brought shame and embarrassment down on the heads of all Israel – he gave that nary a thought, even for a moment. (ibid.)

In any case, this wedding was the last to be held in a graveyard in the land of Israel. The 20th century introduced other methods of combating plague: penicillin, vaccines, baby clinics, modern hospitals, and airy neighborhoods beyond the Old City walls, sparing Jerusalem’s inhabitants the agony of recurrent plagues. And with the founding of the Jewish state, black weddings became a relic of exile and darker days.

Same event, different angle. Dr. Moshe Erlanger’s photo of the orphans’ wedding celebrated on the first of Nisan on the Mount of Olives in 1909 Courtesy of the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Moshe Erlanger Collection

Same event, different angle. Dr. Moshe Erlanger’s photo of the orphans’ wedding celebrated on the first of Nisan on the Mount of Olives in 1909 Courtesy of the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Moshe Erlanger Collection

Further reading:

Jacob Barnai, The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: Under the Patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine (University of Alabama Press, 1992).

Sara Barnea

A tour guide specializing in theMount of Olives cemetery, Barnea holds an MA in Israel studies from the Schechter Institute in Jerusalem

–

Crashing the Wedding

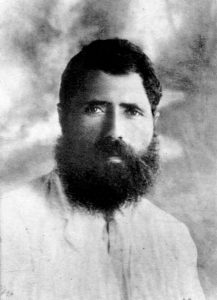

Yosef Hayim Brenner’s caustic but colorful description of a black wedding encapsulates the pioneer Zionist writer’s critique of the traditional Jews he encountered in Ottoman Palestine’s holy cities

Three months after his arrival in Palestine in 1909, Yosef Hayim Brenner completed his novel Between the Waters. Published that fall, the novel provoked fierce debate among readers for its unflattering, firsthand picture of life in the land of Israel.

Brenner’s unfavorable impressions of his new home were clearly those of an outsider not yet familiar with the nuances of the society into which he’d been transplanted. Scathing depictions of the colonies struggling to establish themselves with Baron Rothschild’s support, of Jerusalem’s largely penniless Orthodox Jews, and of the overall state of affairs in Ottoman Palestine fed on Brenner’s sense that everything around him was rotten. His book was an outcry against the exilic habits that threatened any chance of building a new kind of existence for the Jewish people.

The inspiration for Brenner’s plot – including his scorn for graveyard weddings – came from an article published by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda in Ha-zvi in 1909.

On the evening of the day they were forced to move little Hadassa to Rothschild Hospital, a black wedding canopy was raised in the graveyard.

All of Jerusalem came out to watch the show – from Yemin Moshe, Me’a She’arim, Mishkenot, the Bukharian Quarter, and everywhere else. Jerusalem, guardian of our fathers’ heritage and of memories of bygone days, which survives on scraps from the tables of the House of Israel all over the world yet represents all the combined generations of Jewish genius in all its glory; which confines its youthful bridegrooms to study halls and Talmudic academies and shaves the heads of its young brides […]; which provides the entire Diaspora of the sons of Jacob with prayer vigils, herbal remedies, donation receipts, and promises to pray at its shrines. Jerusalem of handouts, sunk low, like a can of worms in a trash heap of inactivity, a dunghill of unchanging obsolescence – [the city] croaked, teemed, and rejoiced on that day.

The crowd was varied – of all origins and communities. Men in white undershirts, sandals, and stockings, in mottled coats and wide sashes; children thin as matchsticks, their long sidelocks swinging; loathsome, witchlike women bereft of magic powers; tottering, wild-eyed ignorant-faced virgins, their natural intelligence stifled. And over them all – beadles, wastrels, hermits, charity officials, wardens, shofar blowers, all manner of blind, impoverished, and sick; the elderly, with canes and without; Talmud students from all the study halls and cloyses. All these form the fabric and livelihood of the holy city.

There were also a few curious Christians. Armed with binoculars and cameras, in traveling gowns such as only they wear, female English tourists stood by, their slim, tall frames and peculiar, dry, impersonal features suggesting three monkeys side by side.

Among the Jerusalem Jewish intellectuals in attendance was a representative of the Hebrew press, a warm young man full of curiosity about everything, who stood and worried throughout about what kind of impression this unpleasant display would make on the European Christian tourists. “Woe,” he cried anon in his unique brand of Hebrew, “for shame!”

The Englishwomen were divided as to whether any of this was interesting. Only one actually yawned, but all chattered plentifully and sadly observed that among “these people” there was none of that religious ecstasy they’d expected to find in the Jewish people’s graveyard.

“The groom! Oy, the groom is running away from the wedding!” A murmur passed through the crowd. The spectators stirred: “Oh! What do you mean? Why?”

The fool of a bridegroom had carried out his threat. He’d warned repeatedly that until he was paid the whole dowry, he wouldn’t agree to the marriage oaths. And indeed he didn’t!

The Etz Hayim Talmud students totally agreed with him. Nobody likes to be cheated.

“What do the beadles think they’re doing?” others objected. “Are there no rules in Jerusalem?”

“Am I to imagine that redemption has come?” quipped the journalist.

“Now the curative power [of the graveyard wedding] won’t work at all,” joked one of the intelligentsia.

“And what will work, then?!” a young man pounced on him. “Will books save the world? Huh? Or maybe Zionism?” (Yosef Hayim Brenner, Between the Waters [Ha-kibbutz Ha-me’uhad Publishing, 1980], pp. 66–8 [Hebrew])

Yosef Hayim Brenner

This article was published in issue 53 | Av 5780 | July 2020

Post-script: History Repeats

Black weddings seemed indeed to have been relegated to the graveyard of obsolete ancient Jewish customs, until the end of July 2020, when an Israeli television channel broadcast footage of the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods of Bnei Brak during the first wave of COVID-19.

The film highlights unusual and surprising situations; frightened children, families split by isolation, Israeli soldiers removing chametz from every street corner as Pesach approached, prayer services in parks and driveways, a municipality taken over by the army, matza baking with social distancing, a rabbi opening his Yeshiva in a corona isolation facility, a funeral devoid of mourners, and, perhaps strangest of all:

A black wedding canopy surrounded by a small crowd, standing out starkly against a white background. As the camera angle widens, the location suddenly leaps into focus – a graveyard full of white marble tombstones.

A long-forgotten custom is suddenly back, right in the middle of twenty-first century Israel. And this time, the responses are somehow not as cynical as they once were.

The rabbi’s address to the couple standing beneath the black canopy in Bnei Brak now strikes a different chord:

We hold a wedding in a cemetery because this is where man knows that he is truly nothing, nothing at all. From dust you cometh and to dust you shall return. Man is nothing. There is only God.

The few guests present are not defiantly proclaiming life’s victory over death. In silent humility they are cognizant of their own limitations, their own mortality. Before He who determines all life, “there is only God.”

A black wedding in the cemetery in Bnei Brak, March 2020

A black wedding in the cemetery in Bnei Brak, March 2020A still from the film: By the Grace of Heaven. directed by Yariv Mozer