Seldom can any individual distill the defining events of his sojourn in this world into a single sentence. Yet sometimes a few words from a familiar, seminal text can evoke just such a sense of identification and déjà vu.

As Umberto Ecco commented in his Name of the Rose, “ […] this explains why we often find in the margins of a manuscript phrases left by the scribe as testimony to his suffering.”

Such is the heartbreaking marginal note recorded during the last decade of the 14th century in the illuminated Passover Haggadah handwritten by Yaakov ben Shlomo Ha-tzarfati. One can easily picture him weeping over the page in his haggada on which he’d carefully inscribed the names and mnemonic of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, including that of dever (pestilence), which in the Exodus narrative killed only cattle but in the 14th century denoted the Black Plague.

Within months, the “Black Death” had consumed three of Yaakov’s progeny, leaving him inconsolable. Unable to complete his handiwork without some mention of how he, too, had been stricken by one of the plagues of Egypt, Yaakov ben Shlomo referred readers to the end of his magnum opus, Yeshuat Yaakov (Jacob’s Salvation).

Whoever wishes to truly know, without dissembling, why Rabbi Yehuda gave this mnemonic and none other [for the Ten Plagues – detzakh, adash, be-ahav], the answer is given in a book I authored, which I called Jacob’s Salvation. (Wolff Haggada)

There, in a treatise entitled Evel Rabbati (Great Mourning), he’d recalled his children’s tragic, painful deaths during the resurgence of the Black Plague in Avignon in the autumn and winter of 1382-3.

Plague after Plague

Evel Rabbati records the final moments of Yaakov ben Shlomo’s daughter Esther (Trina), in the spring of 1383. Only a few months earlier, Yaakov himself had almost died of the Black Plague. He’d recovered only to find that his son Yisrael (known in French as Monriley) had also been infected. Yaakov buried Yisrael amid the holiest days of the Jewish year, in Tishrei 5143 (October 1382). Shortly afterward, a second child, Sara, whom her father described as possessing “wisdom of the heart, intelligence and knowledge,” succumbed on her first wedding anniversary, roughly a week before Purim, on 5 Adar (February 8, 1383). Esther’s death was the last straw. Thus, the note found in the Wolff Haggada, as Yaakov’s masterpiece has become known (see Lost, Found, and Fought Over, pp. XX), obliquely refers us to the devastation of the Black Plague as the story of his life.

I tell everyone that because of this plague, all my days are pain. Even on Sabbaths and holidays, I sigh and weep with grief, and even now I write in tears […]. (Evel Rabbati, p. 84)

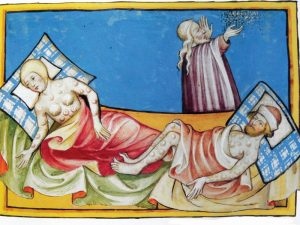

Accused of trapping spiders, poisoning wells, and all other means of spreading plague, the Jews of terrified Europe were defenseless scapegoats in the chaos. Jews in discriminatory headgear, burning to death.

Yaakov ben Shlomo had been born into the chaos accompanying the first outbreak of the pandemic known as the Black Plague, in 1348-9. Little is known of his early years or of the traumatic events he surely experienced. Europe plunged into darkness as Church control slipped and religious movements such as the Flagellants overran the continent, seeking scapegoats and massacring Jewish communities. In all likelihood, Yaakov’s parents found refuge in the papal states of southern France. A contemporary chronicle describes the devastation:

In this and the following year [1348–9] there was a general death of people throughout the world. It began first in India, then it passed to Tharsis, thence to Saracens, Christians and Jews in the course of one Easter to the next […]. In one day there died 812 people in Avignon according to [a] reckoning made by the pope. […] 358 Dominicans died in Provence in Lent; in Montpellier only seven friars were left from 149 […]; at Marseilles only one Franciscan remained of 150 […]. (Knighton’s Chronicle 1337–1396, ed. and trans. G. H. Martin [Oxford University Press, 1995], p. 94)

The plague can indeed be traced to Mongol invaders and caravans of merchants sweeping across Asia, who transmitted the disease via rats and fleas. Before succumbing themselves, these men resorted to one of the first instances of biological warfare at its most literal, catapulting their dead over the walls of the besieged Black Sea port of Caffa. Sailors and refugees fled in Genoese trading vessels, bringing the scourge to the Sicilian port of Messina in October 1347.

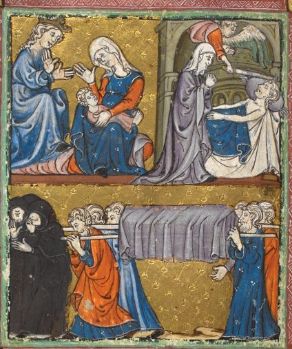

The sumptuous Golden Haggada was written and illuminated in Catalonia, Spain, around 1320, before the “Black Death” hit Europe. It describes scenes illustrating the tenth plague, the death of the firstborn

Those gathering at the docks to meet the incoming ships were horrified at the sight of the dead and dying. Though the Sicilian authorities hastily drove the ships away, the damage had been done. Plague spread throughout Europe within the year, killing over a third of the population – some twenty million people. Both clergy and laymen desperately attempted to liquidate the purported source of the outbreak: the Jews. Herman Gigas, a Franciscan friar from the German region of Franconia, recorded both the hearsay and its horrific consequences:

In 1347 there was such a great pestilence and mortality throughout almost the whole world that in the opinion of well-informed men scarcely a tenth of mankind survived. The victims did not linger long, but died on the second or third day. The plague raged so fiercely that many cities and towns were entirely emptied of people. In the cities of Bologna, Venice, Montpellier, Avignon, Marseilles, and Toulouse alike, a thousand people died in one day, and it still rages in France, Normandy, England, and Ireland.

Some say that it was brought about by the corruption of the air; others, that the Jews planned to wipe out all the Christians with poison and had poisoned wells and springs everywhere. And many Jews confessed as much under torture: that they had bred spiders and toads in pots and pans, and had obtained poison from overseas; and that not every Jew knew about this wickedness, only the more powerful ones, so that it would not be betrayed.

As evidence of this heinous crime, men say that bags full of poison were found in many wells and springs, and as a result, in cities, towns, and villages throughout Germany, and in fields and woods too, almost all the wells and springs have been blocked up or built over, so that no one can drink from them or use the water for cooking, and men have to use rain or river water instead.

God, the Lord of vengeance, has not suffered the malice of the Jews to go unpunished. Throughout Germany, in all but a few places, they were burnt. For fear of that punishment many accepted baptism, and their lives were spared.

This action was taken against the Jews in 1349, and it still continues unabated, for in a number of regions many people, noble and humble alike, have laid plans against them and their defenders, which they will never abandon until the whole Jewish race has been destroyed. (Chronicle of Herman Gigas [1349], quoted in Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death [Manchester University Press, 1994], p. 207)

Panic and Chaos

The initial outbreak of the Black Plague in Yaakov’s early years caused wholesale panic, depopulating entire towns. Crops were left to rot unharvested, resulting in famine and starvation. Those infected were isolated, often locked within their sealed homes to die painfully alone. A letter written by one Louis Sanctus of Yaakov’s native Avignon and dated April 27, 1348 provides graphic illustration:

It has come to pass that, for fear of infection, no doctor will visit the sick (not if he were given everything the sick man owns), nor will the father visit the son, the mother the daughter, the brother the brother, the son the father, the friend the friend, the acquaintance the acquaintance, nor anyone a blood relation – unless, that is, they wish to die along with them at once. And thus an uncountable number of people died without any mark of affection, piety, or charity – who, if they had refused to visit the sick themselves, might have escaped. […]

To be brief, at least half the people in Avignon died; for there are now within the walls of the city more than seven thousand houses where no one lives, because everyone in them has died, and in the suburbs one might imagine there is not one survivor […]. (ibid., p. 43)

The last rites – and particularly confession – could no longer be administered by the Church. Ralph of Shrewsbury, bishop of the English town of Bath, documented the extent of this calamity in his diocese:

We understand that many people are dying without the sacrament of penance, because they do not know what they ought to do in such an emergency […] if, when on the point of death, they cannot secure the services of a properly ordained priest, they should make confession of their sins […] to any layperson, even to a woman, if a man is not present. (ibid., p. 271)

Dying a “good death” is of paramount importance for a Christian. A person’s last moments in this world are considered a crucial test, passed only when the departing soul has been prepared for the next life by a priest. Prolonged illness or old age allow ample time for the confession and penance that secured salvation. The souls of those who die suddenly, on the other hand, with no priest to administer the rites of penitence, the Eucharist, and Extreme Unction (Final Anointing), are doomed to everlasting torment in Hell. The Black Plague thus left the masses terrified of being deprived of the rituals safeguarding their ascent to Heaven.

Our scribe’s depictions of his daughter Esther’s last moments, in the pandemic of 1383, could not paint a starker contrast.

The Soul’s Farewell

Stricken by the plague after her father’s near fatality and the deaths of her brother and sister, languishing on her deathbed a few weeks after Purim (26 Adar 5143), Esther requested the traditional rite of Viddui (confession). First her hands had to be washed, then she recited the prayer in the presence of all those gathered around her. Apparently, however, Esther spoke much more than the formal Viddui text as we know it today. As Yaakov wrote of her final words:

It would have been unbelievable had it not been heard by the crowd of men, women, and children standing in the antechamber. Those who came to console me heard a speech inspired by the Almighty. (Evel Rabbati, p. 76)

In the outbreak of 1383, unlike that of 1349, loved ones were no longer abandoned to their fate. Perhaps by now, the survivors were accustomed to the recurring plagues of the 14th century and no longer reacted with terror and panic. In this light, the fact that Esther’s last moments were witnessed by family and friends is highly significant.

The bereaved father highlighted his daughter’s erudition:

[She] knew how to read the Bible and could eloquently pronounce the verses with the requisite accents and vocalization, without stammering. (ibid., p. 77)

He noted Esther’s determination to observe every detail of Jewish tradition even in her final hours. Despite her terrible agony, she issued clear instructions. Her money was to be given to charity. Her uncle Moshe – whose priestly status forbade him proximity to a corpse – was to leave the room immediately, as she was about to die. She asked that candles be lit, signifying the departing soul, and reminded her husband not to touch her, for she was ritually impure as a result of her menstrual period. In addition, despite past fears of contagion, she bequeathed her clothes to the needy.

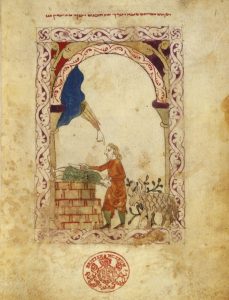

Women clean for Pesach, reaching up to ceilings and down to skirtings, while men search hidden crevices by candlelight for crumbs, each playing their part in the ritual of removing leaven from the home. Illustration from the Golden Haggada, circa 1320

With virtually her last breath, Esther ordered a pregnant woman to keep her distance lest she miscarry or fall prey to infection. Esther’s thoughts then turned to her recently deceased sister, Sarah, and to her own burial, requesting to be laid to rest with her wedding ring and the “pure, white headscarf” of a married woman. At the same time, she wisely suggested precautions to prevent embarrassment later:

Indeed you will cry for Sarah, my lady, my sister, the fairest among women, my dove, and my undefiled one. Beside her, make a place to bury my body, because she taught me knowledge. And you, my beloved [father] and master, please remove the rings from my fingers […] so they won’t fall off or become lost, and you won’t suspect any innocents as the grieving crowds lament like Philistines. But on my little finger, leave the ring with which my husband married me and designated me his own among women. This you will do, and furthermore, place the pure, white headscarf on my head to set an example, and as a good omen for the life of my man, my husband. (ibid., p. 80)

Having dealt with these details, Esther faced the future. Still childless, having been married for only a year, Esther knew that her husband, Natan, would remarry. Should a daughter be born, the dying woman asked that the infant be named in her memory,

so you, my father and teacher, will find a little pleasure. And after I am gone, my mother will be somewhat consoled by dandling her on her knees. (ibid., pp. 78–9)

Esther rebuked her aunt for suggesting that her younger sister, Yentish, step into her shoes as Natan’s wife, pronouncing the girl too young for her “great and mighty Natan” (p. 79). She requested that an influential family friend, Don Comfort, resolve a financial dispute between Natan and Astrug of Carcassonne, his former partner, lest their case wind up in a non-Jewish court, contrary to Jewish law. Dispensing peace as well as wisdom with her final breath, she instructed her father to reunite his household with Natan’s family, that the in-laws should once again “eat bread at one table, as at first” (ibid.).

Deathbed Rites

Knowing that immediately upon her demise, the women present would begin purifying her body for burial, Esther asked them to allow her father to remain by her deathbed awhile before they covered her corpse and placed it in the casket.

Yaakov ben Shlomo declared that his daughter’s last confession would atone for all who heard it.

Even if she had no testimony on her behalf other than the movement of her lips, the pleasantness of her voice, and the loveliness of her speech as she prepared for death, these would be sufficient grounds for showering her with praise. (ibid., p. 77)

Unlike the Christian superstitions surrounding the last rites, the deathbed confessions of the Jews of Provence as reflected in Evel Rabbati evidently had nothing to do with ensuring a soul’s entry into the “world to come.” Judging by Ben Shlomo’s account, his contemporaries had no specific format for Viddui or any other prayer to be recited prior to death. The Talmud, for instance, discusses deathbed rites only in general terms, without indicating whether Viddui should be a private affair or if a prayer quorum is required:

Our rabbis taught: If one falls sick and inclines toward death, he is told, “Confess,” for all put to death make confession. (Shabbat 32a)

In a mid-14th-century halakhic work from Provence, however, Yeruham ben Meshulam expanded the Viddui tradition, basing his rulings on Nahmanides (1194–1270, Spain and Tiberias) and Aaron Hakohen of Lunel (circa 1300, Narbonne). His Sefer Toledot Adam Ve-Hava (1350) is discussed in depth by scholar Elliot Horowitz, who concludes that Viddui became a formal ceremony only in the 1300s:

Rabbi Yeroham [sic] not only prescribes the washing of hands before the recitation of pre-death confession, but insists also that this be done with ritual blessing. The dying Jew is also instructed to don his prayer shawl before reciting confession. (Elliot Horowitz, “The Jews of Europe and the Moment of Death in Medieval and Modern Times,” Judaism 44, no. 3 [summer 1995], p. 274)

Hand of God

Aside from being the scholarly author of Yeshuat Yaakov (which examines the divine nature of miracles) and a master scribe, Yaakov ben Shlomo was a Paris-trained physician and may well have been the same Yaakov ben Shlomo described as the doctor attending to the family of Pope Clement VI. Nonetheless, other than Ben Shlomo’s attempt to feed Esther broth (which she could no longer even swallow), Evel Rabbati mentions no medical treatment. Yaakov regarded the plague as an act of God against which medicine was useless. Evel Rabbati thus attacks the “philosophers,” as Ben Shlomo calls those who dismiss the biblical plagues and other wonders as mere allegory:

They maintain […] that the tales recorded in the book never happened at all, save as an allegory for the enlightened. And the reason [for their doubts], they aver, is the length of time [that has passed] since those early days, so that all has been forgotten and no memory remains of what was then [to be passed down] to those coming afterward. (Evel Rabbati, p. 86)

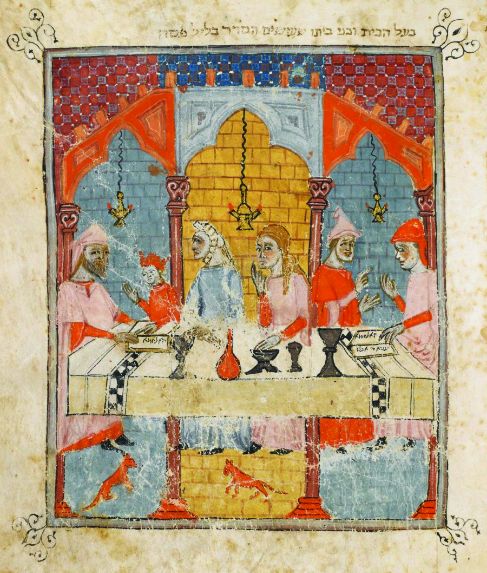

Medieval family celebrates the Seder together. Each man has a haggada; the women turn to listen while tasting the food. Known as the Sister Haggada for its illustrations’ similarity to those of the Golden Haggada, this volume was also crafted in 14th-century Spain, though a few decades later

In the margin of his haggada, Yaakov ben Shlomo immortalized the sad epic of his plagued life next to the acronym of the Ten Plagues, specifically pestilence. For him, his tragedy proved that the suffering of Job, for instance, actually occurred. The rationalists, in contrast, “who abandoned the literal meaning of the Hebrew Bible, were also those scholars who repudiated the notion of plague as divine punishment, interpreting it instead according to the laws of natural science” (Susan Einbinder, No Place of Rest: Jewish Literature, Expulsion, and the Memory of Medieval France, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, p. 113).

With understandable trepidation considering his medical background, Yaakov records how Esther kissed her family goodbye:

And I kissed my sweet one, my daughter, on the familiar lip. And she seized me and kissed me, until I feared that disaster would overtake me and I would die. Then she kissed [her husband’s] brothers and relatives, and her relatives, with kisses of the mouth that were sweeter than honey. Afterward she lost her breath and nearly died with a kiss.

When her soul departed, word spread throughout our community that she had died, and people were aghast. Young and old, their hearts went out to her, for she was no more: Esther was taken away to the house of the King, the Lord of Hosts. (Evel Rabbati, pp. 81–2)

Life and death in the hands of the Almighty. God reaches down from heaven to stay the hand of Abraham, raised to smite his son Isaac upon the altar. Hispano-Moresque Haggada, circa1300, central Spain; among the earliest known illustrated haggadas

In view of Esther’s strict observance of Jewish law, it is surprising that she kissed her male relatives. This gesture, the stuff of Hollywood melodrama, would surely be censored by most observant Jewish communities today. How is it that Esther’s last act was a kiss? Why did she not choose to die like Rabbi Akiva and other martyrs, with a prayer on her lips?

For Esther, a “good death” meant leaving this world in an orderly fashion, expressing her deep love for her family. Perhaps she also sought to differentiate her end from those of the many martyrs preceding her, butchered or burnt at the stake as in Herman Gigas’ account above. “Hear O Israel,” the affirmation of God’s oneness, was their final, defiant denial of the Christian Trinity.

But for Yaakov ben Shlomo, Esther’s death too was fraught with meaning. To die of the Black Plague was to die by the hand of God. Like her father, Esther apparently accepted her calamity and trial of belief with a whole heart. Her confession was a model of Provençal Jewish tradition. Even her tender kisses were biblical allusions, drawn from metaphors of devotion in the Song of Songs. And in Jewish exegetical tradition, Moses himself relinquished his soul to God’s kiss, signifying the ultimate human dissolution in the divine. The lesson Yaakov Hatzarfati took from his daughter’s deathbed and inscribed in the margin of his haggada was a bold affirmation of Jewish faith and observance in the face of utter tragedy.

“And Miriam answered them: Sing unto the Lord” (Exodus 15:21). Miriam singing while her companions grasp lute and timbrel; illustration from the Golden Haggada. Unlike the lavishly illustrated haggadas of Spain, which abound with human images despite the biblical prohibition, Yaakov ben Shlomo’s volume from Avignon was embellished only by enlarged, colored lettering

*

Further reading

Susan Einbinder, No Place of Rest: Jewish Literature, Expulsion, and the Memory of Medieval France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), pp. 112–36; Einbinder, “Theory and Practice: A Jewish Physician in Paris and Avignon,” AJS Review 33, no. 1 (April 2009), pp. 135–53; M. Garel, “The Rediscovery of the Wolff Haggadah,” Journal of Jewish Art 2 (1975), pp. 22–7; Elliot Horowitz, “The Jews of Europe and the Moment of Death in Medieval and Modern Times,” Judaism 44, no. 3 (summer 1995), pp. 271–81; Rosemary Horrox, ed. and trans., The Black Death (Manchester University Press, 1994), pp. 41–4; Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous Fourteenth Century (Random House, 1987), pp. 92–125.

*

Dedicated by the author in memory of his mother, Esther bat Yaakov