Soprotimis

The mass Jewish emigration from Russia and Poland around the turn of the 20th century was a historic upheaval with far-reaching social, political, and humanitarian consequences. Many organizations were created to resettle the staggering number of emigrants, resulting in archives full of fascinating stories.

Soprotimis (Sociedad Protectora de Inmigrantes Israelitas) was founded in Argentina in 1922 to absorb the many thousands of Jews arriving from eastern Europe. The organization’s archive includes no fewer than 26,000 files of aid requests and subsequent correspondence. From the mid-1930s, however, most Jews applying to the organization were seeking help finding relatives to vouch for them, enabling them to escape Europe. And once World War II ended, the files swelled with correspondence regarding Holocaust survivors searching for family and acquaintances in Latin America.

A different story altogether, spanning several files, concerns eleven Jewish families from Syria. Forty-nine people in all, they requested Soprotimis’ assistance in fleeing the country in 1958. The families were staying in Qamishli, a town not far from the Turkish border, awaiting permits to leave Syria. The correspondence describes them as farmers.

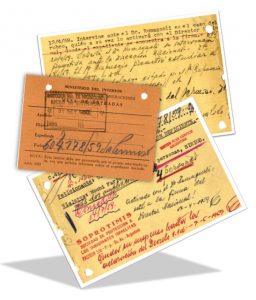

File cards from the Soprotimis archive, including updated information on each family’s whereabouts as it moved from one continent to another

The Argentine government was then encouraging farm workers to settle the great wastelands of Patagonia. So the plan was to send the Syrians to the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) agricultural colony founded by Baron Maurice de Hirsch in the southern Argentinian province of Rio Negro – on the assumption that they were a perfect match for Argentina’s needs,and vice versa. The initial appeal to Soprotimis came from the Sephardic community in Buenos Aires, one of whose donors was related to the Syrian families and therefore negotiated on their behalf with the welfare organizations.

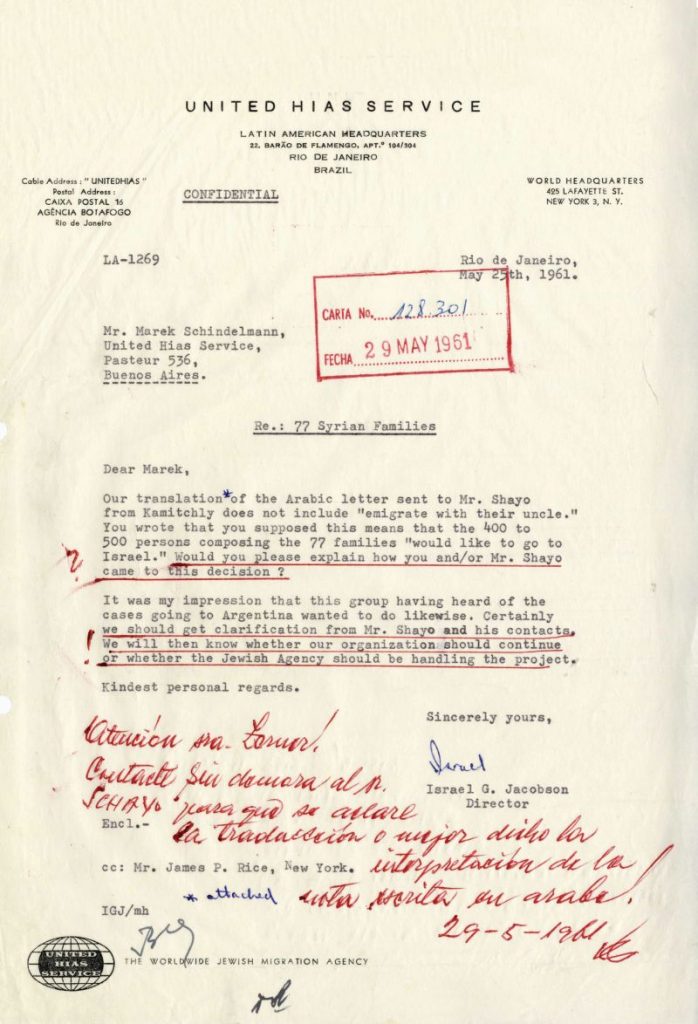

The group’s exodus dragged on from 1959 to 1962 and involved the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS)as well as Soprotimis. Much of the relevant correspondence between the two organizations is labeled “classified.” Between the lines, it emerges that Jews were actually exploiting Argentina’s immigration policy to get out of Syria and settle in Israel. But who exactly knew that, and who was simply taken advantage of?

Moving Out

The first two households left Syria for Argentina only in the winter of 1961. Tremendous efforts preceded their departure. HIAS and Soprotimis had gotten them Argentinian entry permits, which they’d submitted to the Argentinian consul in Damascus in October 1960. He was then to stamp a visa on their Syrian exit documents. Yet Syrian bureaucracy and political instability necessitated countless extensions of the paperwork. A relative in Argentina also paid the astronomical exit fees demanded by the Syrian government. Meanwhile, the families were growing. Then one newborn died, creating a discrepancy between the immigration documents and the immigrants themselves.

On February 27, 1961, the two families finally set sail from Beirut to Italy. Then events took a strange turn. When the ship docked in the Greek port of Piraeus, a pregnant woman from the group asked to see a doctor. Though pregnancy and seasickness are hardly an unexpected combination, all ten members of the two families accompanied her to the hotel where the doctor’s appointment was to take place. Two Jewish Agency officials just “happened” to be there and persuaded them to continue on to Israel instead, as their ship had left without them. Subsequently interviewed for official protocol by HIAS representatives, they claimed they’d been unable to locate the HIAS agent in Greece who could have helped them proceed to Argentina.

Both families settled in Kfar Saba, where they had relatives and found employment, and one even Hebracized its name. But then all concerned realized that by diverging from the original plan, they were playing with fire. Their choice of Israel as their final destination, greatly reduced their fellow Syrian Jews’ chances of receiving exit clearance. So the two families wrote to their Argentinian sponsor, saying they’d been deceived by the Jewish Agency officials and brought to Israel, but their real preference was Argentina.

By now, however, they all had Israeli passports. So their Argentinian entry permits had to be transferred from their expired transit documents to these new passports. The Argentinian consul in Tel Aviv saw to all that, but then Israeli bureaucracy became the main hurdle. The Ministry of the Interior had to revoke the families’ status as new immigrants, the Foreign Ministry had to process their exit from the country, and the Treasury had to waive the exit duties and travel tax. The adult men under age fifty needed an exemption from army service as well.

Both families wanted the Jewish Agency to promise to help them come back to Israel if they didn’t like Argentina, but no such guarantee was given.

Back to the Diaspora

The two families finally set sail for Argentina via France at the beginning of June 1961. Fellow travelers and officials recorded that the transplants were disgruntled and left a poor impression. Correspondence between the aid organizations describes their behavior as “primitive” and their children as unruly. En route from France, they even insisted on and first-class cabins and an HIAS escort.

Their arrival in Argentina was no less fraught. The staff that greeted them had to pay hefty bribes to get all their baggage through customs without inspection or duties, then transport it to Patagonia. The families wouldn’t allow their children to spend the night at their sponsor’s house, demanding instead that Buenos Aires’ Sephardic community provide them with hotel rooms and food for the two days they spent in town. And they insisted on an interpreter for the thirty-hour train ride to the far south.

In Rio Negro, three Arabic-speaking representatives of JCA and Soprotimis were waiting at the station to take them to their new, fully furnished home in the General Roca colony. A letter from the JCA official in Rio Negro to the Latin American chairman of HIAS describes their dramatic arrival in Patagonia:

Men, women, children, and a hundred and one packages were all on the platform […] when a loud argument broke out in Arabic, accompanied by much hand waving […]. In the end we got the message – the M. family refused to go to the colony. They wanted to live only in town, not on a farm. They couldn’t be persuaded to accept the house that had been prepared for them for even one night […]; our people were embarrassed […]. At one point P. M. himself ran for the police, and S. M. and his five children began shouting hysterically. The locals suspected it was all a performance […]. After two hours of trying, we gave up and began looking for a hotel for them […].

The next day, too, all efforts were in vain, and they insisted they’d been promised tractors and wheat fields in town. When no answer was forthcoming, they demanded at the top of their lungs that they be returned to Buenos Aires at once […]. None of our promises to find a solution, even to locate a Jewish doctor to take care of the pregnant woman, could satisfy them.

Saturday morning, all ten family members broke into the hotel where the Soprotimis and JCA staff were staying, demanding their immediate return to Buenos Aires […]. The Syrians were shouting, and we couldn’t control them. At one point P. M. picked up a heavy object and wanted to throw it at us. That’s when the JCA clerk realized he had to get rid of them fast. He himself paid for their trip back to Buenos Aires […]. They gathered up their wives and children, who’d been sitting like Gypsies in the corner all the while, [and] went back to the hotel. From that moment, peace was restored in the town.

HIAS and Soprotimis broke off all contact with the families. Realizing that they’d wanted to emigrate to Israel the whole time, the organizations feared they’d be suspected by JCA and the Argentinian authorities of active involvement in the scam. Back in Buenos Aires, the Sephardic community tried but failed to find something suitable for the Syrians elsewhere in Argentina. A telegram from July 9, 1961, reveals that the Jewish Agency sent both families back to Israel.

The Jewish relief agencies were now concerned that their entire global strategy would go down the drain if the Argentinian and Syrian authorities discovered what had happened. So they reported to the Argentinian immigration office on the families’ arrival, but nothing else.

Nearly all the correspondence on file expresses the organizations’ viewpoint. We can only imagine how the families felt about being uprooted again, having already settled into a familiar climate and Jewish community in Israel, only to embark for some godforsaken place near the South Pole. Only one letter reflects this perspective. Having spoken with the emigrants after their return from Rio Negro, a Jewish official – perhaps a social worker – emphasized that the aid organizations urging them to leave Israel had promised one thing, but the reality was quite another. They weren’t told they’d have to lodge their children with strangers, which only added to their fear and disappointment. That, together with their alien surroundings, solidified their yearning for Israel, where they’d felt safe.

Escape Route

A letter from one HIAS employee to another from November 1962, over a year after the first Syrian families had finally returned to Israel, reveals that seven more “farming families” immigrated to the Holy Land using exit permits intended to escort them to Argentina. The method had clearly proven itself, and HIAS hoped to use it to help other families still waiting in Syria.

The eleven households’ exodus set a precedent for another seventy-seven families, numbering as many as five hundred souls, who spent years languishing in a Syrian town on the Turkish border before setting out for “Argentina,” though really headed for Israel.

The first families’ travels opened the door to hundreds more Jewish emigrants from Syria. HIAS files record officials’ wondering whether to transfer such cases straight to the Jewish Agency, so these Jews could be processed as immigrants to Israel

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (http://cahjp.huji.ac.il) rescues, restores, and preserves historical documents concerning the Jewish people from communities worldwide, from the Middle Ages to the present.