The Great Revolt at Gamla

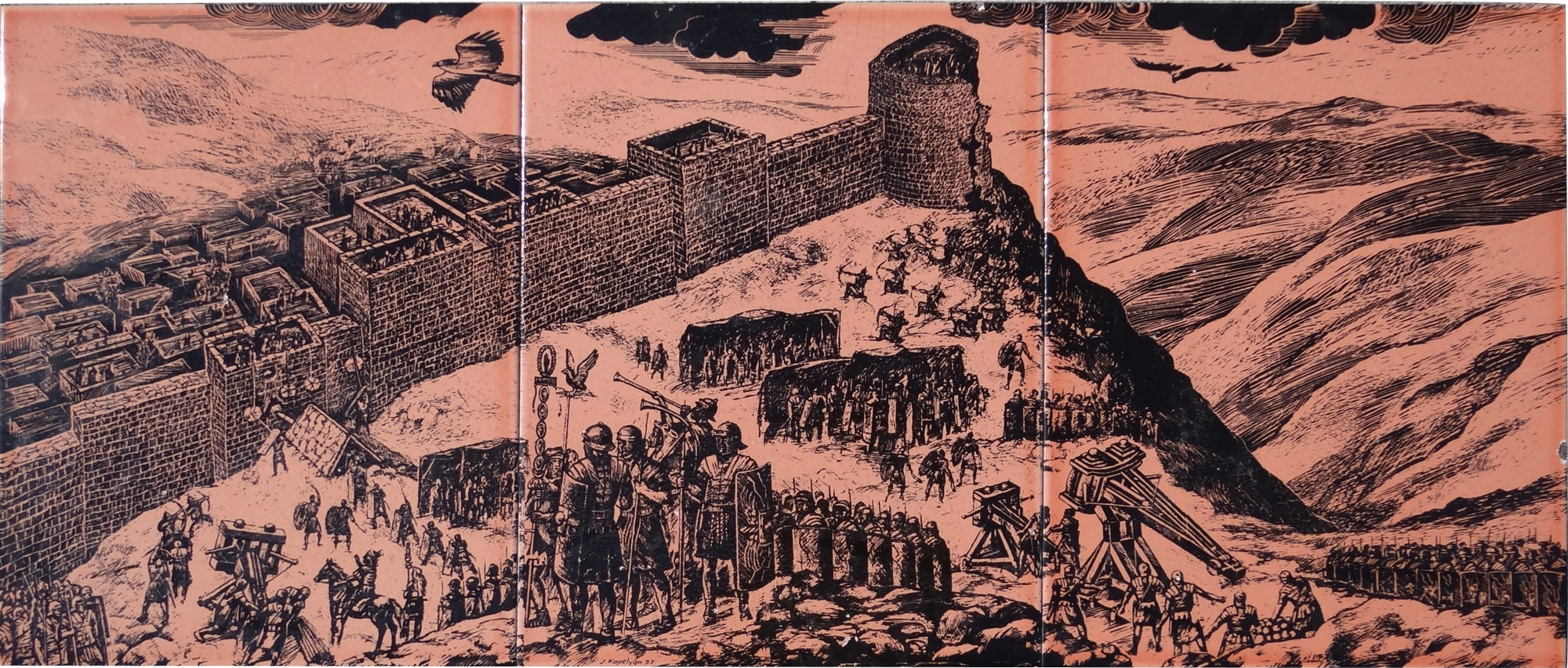

Summer, two thousand years ago. The Great Revolt against the Romans rages through Judea. Weary Jewish refugees climb the steep ravines of the Golan, eyeing the birds of prey circling above. Roman predators as well, eagles emblazoned on their ensigns, will soon spread over the formidable landscape, waiting to pounce. The Jews, some of them fugitives of earlier battles in the struggle for religious and national freedom, seek refuge in Gamla, the only fortified city left in the region.

From the Gamla National Park lookout platform, it is easy to imagine an observer in ancient times accurately recording every maneuver in the battle waged on the hump-shaped ridge below. Tourists flock here, not for the spectacular view of the Sea of Galilee in the distance, or for the vultures silently gliding by. They come to relive the drama of the battle and its tragic outcome. Day after day, over and over, tour guides recount the story of the Gamla siege. All quote the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, the only extant source regarding the sequence of events that unfolded here.

An Unexpected Victory

Although sometimes billed as the Masada of the north, Gamla differed drastically from the famous southern fortress. Masada was a palace turned into a refugee camp. The structures left behind by Herod the Great on that plateau overlooking the Dead Sea became the site of the last stand against the Romans. Gamla, on the other hand, was a thriving city in the Golan. It was only the Roman onslaught throughout the Galilee that left the city teeming with refugees. Whereas the Zealots of Masada died before confronting the Romans in hand-to-hand combat, the Jews of Gamla met the enemy head on. And surprisingly, the vast Roman forces were initially defeated. Vespasian’s army took up positions around the mountain on which the city stood. The Jewish defenders rained arrows and stones from the ramparts but could not prevent the approach of the three Roman battering rams. The defensive walls were shaken and breached, and legionaries poured in “with a mighty sound of trumpets and noise of armor” (Josephus, Wars of the Jews IV, 1:4).

Josephus reports how the desperate defenders

fell upon the Romans for some time … and prevented their going any further, and with great courage beat them back … the Romans were so overpowered by the greater multitude of the people, who beat them on every side, that they were obliged to run into the upper parts of the city. Whereupon the people turned about, and fell upon their enemies, who had attacked them, and thrust them down to the lower parts, and, as they were distressed by the narrowness and difficulty of the place, slew them. (ibid.)

Their way blocked from above by the defenders’ fierce resistance (as well as from below as their companions pressed through the breach in the wall behind them), the Roman soldiers

were compelled to fly into their enemies’ houses, which were low; but these houses being thus full of soldiers, whose weight they could not bear, fell down suddenly; and when one house fell, it shook down a great many of those that were under it, as did those do to such as were under them. By this means, a vast number of the Romans perished … although they saw the houses subsiding, they were compelled to leap upon the tops of them; so that a great many were ground to powder by these ruins, and a great many of those that got from under them lost some of their limbs, but still a greater number were suffocated by the dust that arose from those ruins. (ibid.)

Vespasian himself escaped by the skin of his teeth, forcing his men to retreat. He then “comforted his army, which was much dejected by reflecting on their ill success … because they had never before fallen into such a calamity” (ibid., 6). Their second attack was remorseless. A wild, unseasonable storm wracked the hillside, nearly sweeping the Jewish defenders from their outposts. The wind seemed to hasten the Romans’ attack and turn back the Jews’ arrows. Surrounded, thousands of Jews hurled themselves and their families from the precipices to their deaths, leaving only four thousand to the Roman swords.

While the defeat of Gamla was inevitable, the fierceness of the Jews’ defense and their initial victory leave us wondering. What spurred them to meet the powerful Roman army face to face, after all the neighboring cities had fallen? What made so many roofs collapse beneath the besieging legionaries, trapping vast numbers of them? And why were the Jewish defenders spared?

Built on a Precipice

I believe that Josephus, the Jerusalem-priest-turned-captured-rebel-general – and the original fortifier of Gamla – knew the answer. And his account of these events hints at it. The first clue is his description of Gamla, built on a steep slope:

On its acclivity, which is straight, houses are built, and those very thick and close to one another. The city also hangs so strangely that it looks as if it would fall down upon itself. (ibid. IV, 1:1)

Since the houses collapsed under the weight of the Roman soldiers, Josephus seeks to help matters along by suggesting that the city “looks as if it would fall down upon itself.” Ostensibly, the soldiers’ weight simply provided the extra push. But was Gamla really built in such a ramshackle manner?

While Gamla’s urban planners were challenged by its steep slope, excavations have revealed their skill in overcoming it. Katharina Meisel Galor likens the Galilean/Golan architecture of the Roman Byzantine period to a condominium. (Meisel Galor, Domestic Architecture in Roman and Byzantine Galilee and Golan, doctoral thesis, Brown University 1996). The Tosefta’s depictions of similar sloped settlements indicate that the houses were adjacent to one another, providing access from rooftop to courtyard to rooftop all the way down the mountain. Shmarya Gutman, Gamla’s chief excavator, describes the complex maze of housing blocks connected by parallel and perpendicular streets, alleys, and stairways as a kind of beehive structure. This would explain how the Roman soldiers escaped from the crowded alleys into the houses and onto the rooftops. But why did the roofs then collapse?

Farmers taking up arms against legionaries. Arrowheads, souvenirs of a bloody battle, found in Shmarya Gutman’s eleven-year excavation of Gamla

The Romans were not the first to tread upon Gamla’s roofs. In the agrarian societies of the ancient Middle East, rooftops provided convenient sleeping quarters in the hot summer months as well as storage space for agricultural produce. As such, roofs had to be well constructed. In Gamla, they were made of wooden beams – sometimes whole trunks, sometimes split.

Archeology professor Ehud Netzer, originally an architect, pointed out that roofs in traditional agricultural villages were built to withstand the “stretch stress” caused by the weight of snow, produce, and people. Ceilings and roofs collapsed only if damaged by water seepage, earthquakes, or fire, or as a result of poor maintenance.

As Gutman notes, Gamla’s buildings were sturdy, with walls capable of supporting double stories. Excavations have also shed light on roof construction:

Most of the roofs and ceilings in Gamla’s buildings were made of wooden beams resting on corbels and spanning the width of the rooms. Upon these beams were canes topped by a layer of earth that was pressed by stone rollers, some of which were found in the excavations. (Shmarya Gutman and Yoel Rappel, Gamla – A City in Rebellion [Israel: Ministry of Defense, 1994], p. 111 [Hebrew])

Clearly Gamla’s houses were built to carry the weight of agricultural activity. So what caused them to collapse?

Gamla’s strategic importance was such that for the Romans, its capture took precedence over other campaigns. Abandoning their conquest of the Galilee with Gush Halav still in the hands of rebels, they turned northward to the Golan and Gamla.

The Full Weight of the Legions

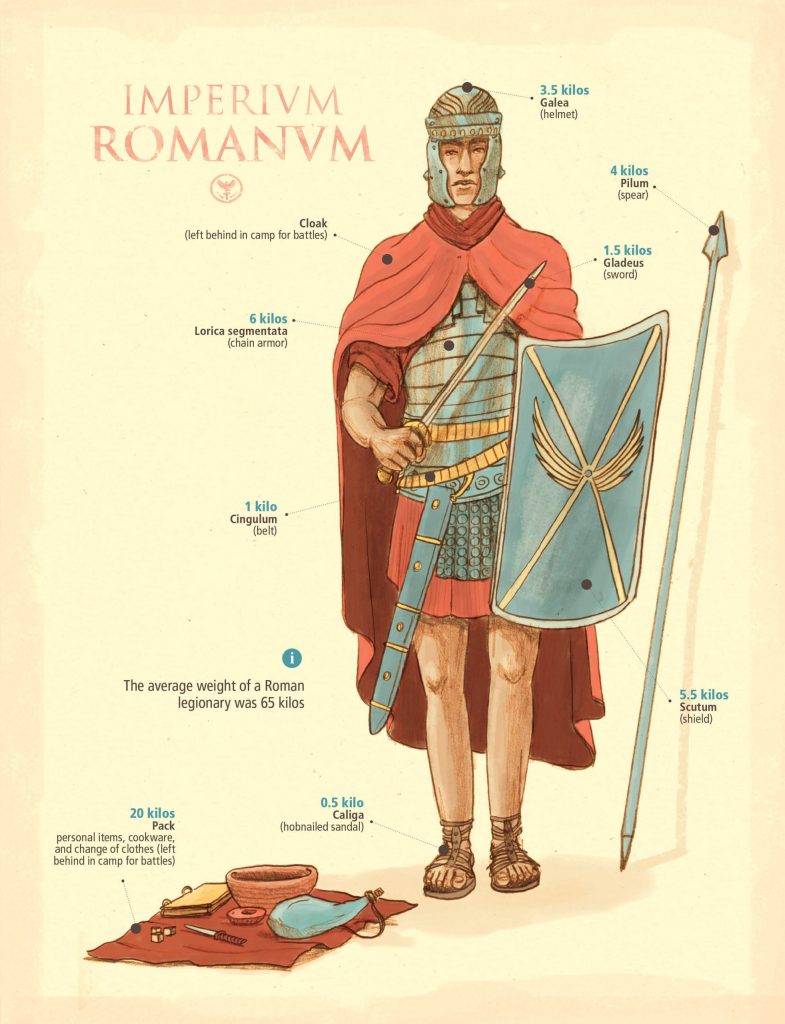

Roman historians relate that the legionaries were taller than average (Apuleius, Metamorphoses 9.39; Tacitus, Histories 4.1). In addition, midrashic sources note the stringent height requirements of the Roman army:

A man came to conscript someone’s son. [The father] said: “Look at my son … how tall he is!” His mother said: “Look at our son, how tall he is!” The [recruiter] answered: … “Let us see whether he is tall.” They measured, and he proved [too] short. (Aggadat Genesis 40:4)

This might explain why Josephus described the houses of Gamla into which the Roman soldiers fled as being “low,” and why these towering fighters sought relief on the rooftops. But the low height of the walls relative to their thickness also contributed to the sturdiness of these homes.

In The Logistics of the Roman Army at War, Jonathan Roth calculates that the average Roman legionnaire was 170 centimeters tall and weighed about 65.7 kilograms. Furthermore, he bore 20–45 kilograms or more of cooking gear, tools, clothing, and weapons – plus rations. But when fighting, legionaries carried only their armor and weapons.

Roth concludes that the Roman soldier’s clothing and weapons would not have exceeded 22 kilograms. This, in addition to his body weight of 65.7 kilograms, totals 87.7 kilograms. The girth of each soldier in full battle dress required a minimum standing space of 80 square centimeters. Thus, every 80 square centimeters of roof space would be subjected to a load of roughly 88 kilograms. On an average roof, measuring 2.25 square meters, nine soldiers could crowd together. Their total weight would be approximately 792 kilograms. Considering that eight of the nine would be standing adjacent to the walls or on the corbels, little of this weight would have been concentrated in the vulnerable center of the roof. Would this load have caused the collapse of Gamla’s houses?

When Is a Roof Not a Roof?

The heavy ceramic jugs of water, grain, and olives stored on an average roof in ancient agrarian societies, in addition to agricultural implements, would have easily topped 700 kilograms. A massive cylindrical stone was also kept on every roof to tamp down a new coat of mud plaster in preparation for the winter rains. Many such stone rollers, weighing 70–100 kilograms each, were found when excavating Gamla. Interestingly, a large concentration was found out of place, adjacent to the breached city wall. Gutman theorizes that Gamla’s defenders used them as defensive weapons, rolling them down onto the Roman soldiers as they approached the wall. So in fact, the roofs of Gamla under siege were relatively empty, with the stores of produce depleted and many rollers missing. They should easily have supported the Romans.

But Josephus alludes to an unexpected phenomenon encountered by the fighters:

And thus was Gamala taken, on the three and twentieth day of the month Hyperberetens, [Tisri,] whereas the city had first revolted on the four and twentieth day of the month Gorpieus [Elul]. (Wars IV, 1:10)

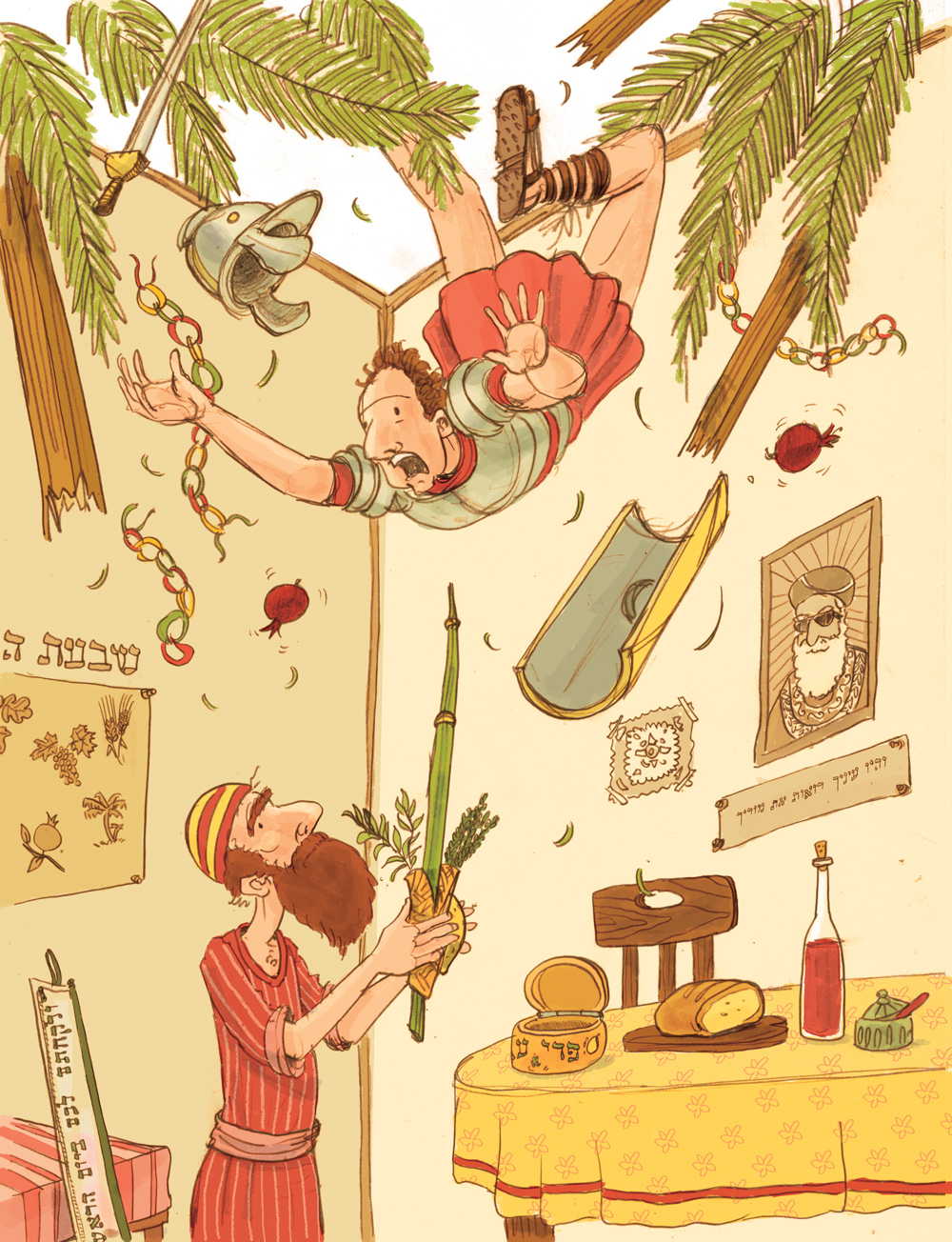

These dates mark the Jewish High Holy Day season. Having celebrated the New Year and the Day of Atonement, the people of Gamla were in the throes of the feast of Sukkot. Besieged, and so unable to leave their town for the prescribed pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem, they would still have observed the rituals of the festival, taking and waving the four species and building sukkot in which to dwell. The Roman siege would have made building materials for these booths – planks, branches, and so on – scarce. Nevertheless, like the Hasmonean rebels (Maccabees II, 1:18 and 10:5–8) some two hundred years previously, Gamla’s defenders presumably observed the commandments of the holiday despite battlefield conditions. Those who lacked proper materials were forced to break through their ceilings, exposing the rafters, then fill them in with leafy branches – known as sekhakh – just as described in the Mishna (Sukka 1:7, 2:8). Knowing nothing of the festival, the Roman soldiers probably mistook the sekhakh covering for produce stored on the rooftops. Thus, the legionaries fell through the flimsy roofing of the sukkot, damaging the rafters. These shattered downward into the buildings, whose walls, no longer supported by the roof beams, caved in. Many soldiers died either from the fall or in the subsequent collapse of the houses. Romans who had sought refuge inside these homes were crushed by their falling comrades. The massive human pressure of the simultaneously advancing and retreating Roman troops caused additional structural damage and collapse. Those who survived, according to Josephus, were subsequently stoned or put to the sword by Gamla’s defenders. Ostensibly, amid the chaos and debris of the collapsing stone structures, those Roman soldiers lucky enough to escape – like Vespasian – did not understand what had happened. Roman observers on the opposite heights saw the houses of the stepped city of Gamla topple like dominoes. These witnesses would have had no inkling of the part played by the sukkot of Gamla in this defeat.

But Josephus knew. He could not include it in his Wars of the Jews, sponsored by the emperor and written to glorify the Romans. Vespasian’s ignorance of conditions in Gamla would tarnish the military’s reputation, as well as implicating Josephus himself for not warning his captors of the city’s precarious roofs during the festival. So he hid the sukkot in the subtext, stating that the Roman attack culminated the day after the festival, thereby implying that the preceding battles were fought during the holiday.

Divine Intervention

Gamla’s Jewish defenders saw the Roman legionaries falling to their deaths through the sekhakh. As far as the Jews were concerned, their insistence on building sukkot even under siege had brought divine intervention to their aid and given them their first victory:

The people of Gamala supposed this to be an assistance afforded them by God, and without regarding what damage they suffered themselves, they pressed forward, and thrust the enemy upon the tops of their houses. (Wars IV, 1:4)

Although Josephus believed these zealots were mistaken, he faithfully portrayed their bravery in action and their stubborn persistence in their ideals.

They saw it as the will of Heaven that the Romans fell through the newly built sukkot of Gamla. Soon afterward, on 23 Tishrei, the same divine will sent a storm wind to turn the Jews’ arrows back upon themselves, while carrying the Roman arrows up to strike them down, spelling the tragic end of Gamla.

Stark contrast: remnants of frescoes from Gamla and stone shot fired from the Roman ballista that battered the city’s walls

Protecting the Holy City

Gutman has his own explanation for the courage of Gamla’s Jewish fighters. The audio-visual presentation at the Gamla visitors’ center shows the elderly archeologist seated among the ruins of the mountaintop city. Turning a polished bronze coin between his fingers, he ponders aloud:

The Romans had waged a bitter war to capture Gamla. The Jews too had fought dauntlessly, even after the entire Galilee had been conquered by the Roman legions. The question is, why did the Jews defend their city so courageously? Was it only their city they sought to protect, or was there a more profound belief involved? Here is a tiny bronze coin. One side bears the Hebrew inscription “for the redemption of,” and the other side, “the holy Jerusalem.” This coin, struck in Gamla during the revolt, proves to me that although the inhabitants of Gamla fought to defend their city, their main concern was Jerusalem. (The Story of Gamla [Herzliya: Shein Productions, 1991])

With these words, Gutman dramatizes the religious nationalism of Gamla’s Jewish defenders. The coin symbolizes the steadfastness of these rebels, who considered themselves the first line of defense not only for their own city, but primarily to block the conquering Roman legions’ path to the Holy City of Jerusalem. And that path, as we have seen, passed through the sukkot of Gamla.