This article was published in issue 58 | Elul 5781 | August 2021

Jonathan D. Sarna and Zev Eleff

Would American Jewry be a satellite of the Old World or develop its own etrog supply? Sukkot, Leopold Pilichowsky, oil on canvas, circa 1895 Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Gruss

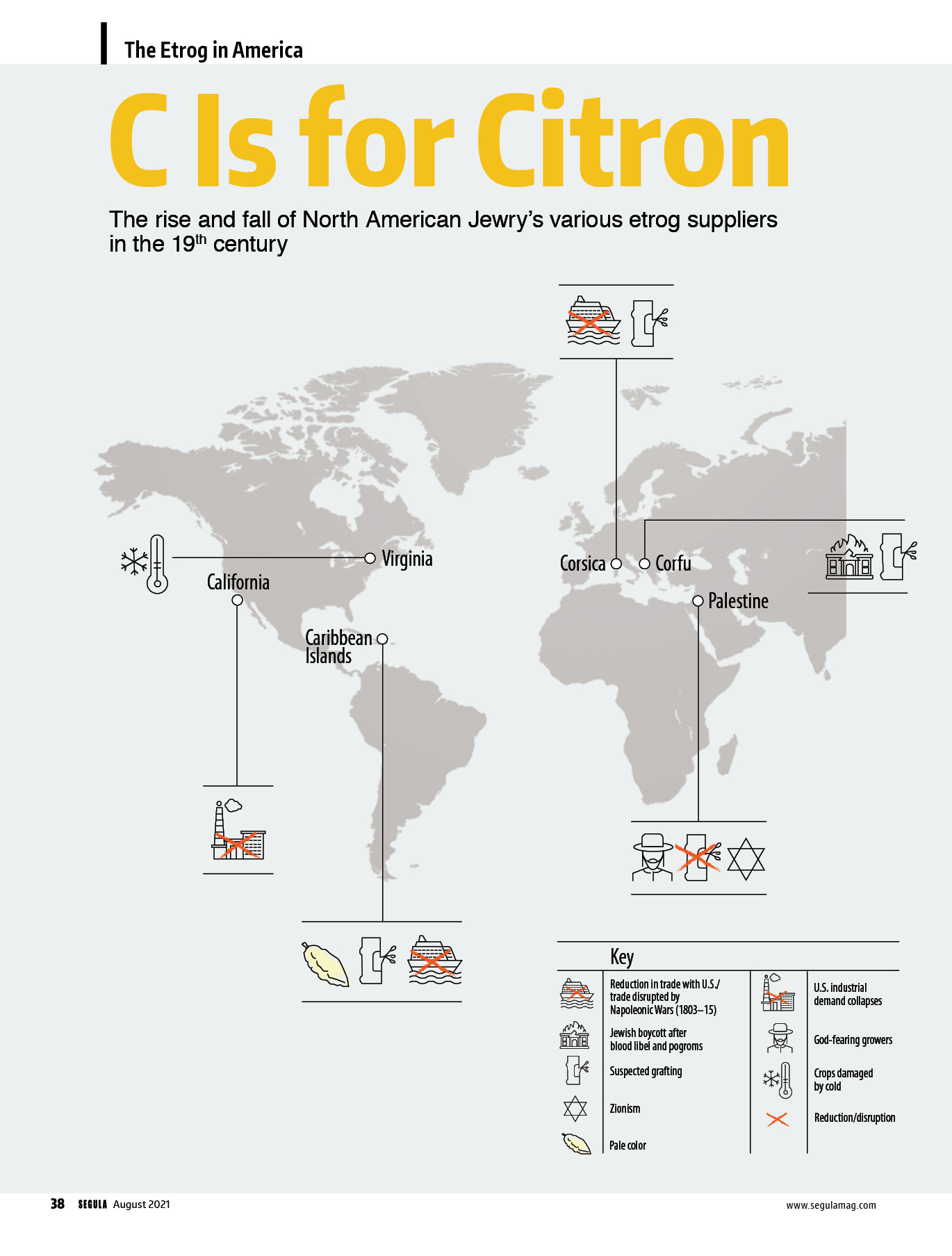

Would American Jewry be a satellite of the Old World or develop its own etrog supply? Sukkot, Leopold Pilichowsky, oil on canvas, circa 1895 Courtesy of the Jewish Museum, New York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Gruss In 1882, etrogim in Los Angeles were a bargain: just twenty-five cents each. “They are beautiful to behold and will compare favorably […] with any that have ever been imported to this country,” reported “Maftir” (Isidore Choynski), West Coast correspondent for the American Israelite. These locally produced etrogim, grown in America’s new citrus capital, appeared to solve what had previously been a significant religious problem. As Rabbi Moses Weinberger of New York explained in 1887:

Only a few years ago, a poor man in New York could not buy a lulav and esrog of his own [as part of the four species taken on the festival of Sukkot]; even the most highly Orthodox had to observe the commandments with esrogim circulated around every morning by poor peddlers. Now it is hard to find any kosher traditional home without an esrog of its own. In many synagogues, especially the small ones, there are as many esrogim as worshippers. (Jonathan D. Sarna, People Walk on Their Heads: Moses Weinberger’s Jews and Judaism in New York [Holmes & Meier, 1982], p. 73)

Within a few years, however, U.S. etrog production had almost completely ceased. Contrary to conventional economic wisdom, expensive, imported etrogim triumphed over the cheaper, domestic variety. To understand why, we’ll have to journey back into the early-19th-century history of the etrog in the New World.

From Corsica to the Caribbean

During the first decades of the 1800s, American Jews had three sources of etrogim: Corsica, the U.S. itself, and the Caribbean. The finest and most expensive came from Corsica, under French rule. These magnificent “diamante citrons” were known among Jews as “Calabrian,” after the region of Southern Italy where they are grown, or as “Yanaver,” a corruption of Genoa, the port from which they were shipped. This species boasted a long, noble history dating back to the Tosafists and is still prized by Chabad and other Hasidic groups.

Sought after for their relative smoothness and rich yellow coloring, diamente citrons are native to the Italian coast as well as Corsica, Sicily, and Sardinia. The species was transplanted to Ottoman Palestine with Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook’s encouragement Photo: Bcohn

Sought after for their relative smoothness and rich yellow coloring, diamente citrons are native to the Italian coast as well as Corsica, Sicily, and Sardinia. The species was transplanted to Ottoman Palestine with Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook’s encouragement Photo: BcohnTwo factors diminished the popularity of these etrogim, however. First, many turned out to be grafted (murkav), which made them much stronger and better able to grow and travel but violated the biblical ban on kilayim (mixing species). Judaism prefers reliable pedigrees for Jews as well as their etrogim. “Intermarried” etrogim are thus prohibited. Fear of grafting drove many Jews away from the Corsican variety; to this day, few of the island’s orchards are considered reliable. Second, trade with France and Italy was greatly disrupted by the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). During this era, very few diamante etrogim made it to the New World; other sources had to be found.

Naval clashes between Napoleon and the British spread all the way from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean, but it was mutual trade blockades in the main that disrupted the flow of goods from Europe to the United States. Duckworth’s Action off San Domingo, 6 February 1806, Nicholas Pocock, oil on canvas, 1808 Courtesy of the Royal Museums Collection, Greenwich

Naval clashes between Napoleon and the British spread all the way from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean, but it was mutual trade blockades in the main that disrupted the flow of goods from Europe to the United States. Duckworth’s Action off San Domingo, 6 February 1806, Nicholas Pocock, oil on canvas, 1808 Courtesy of the Royal Museums Collection, GreenwichFortunately, entrepreneurial American farmers responded eagerly to increased demand for citrons, then used both for making candy and for medicinal purposes. Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book records that he (meaning his slaves) grew the fruit in Monticello, his Virginia plantation – not to supply Jews, of course, but just to see if he could. Others grew etrogim elsewhere. Regrettably, citron trees proved extremely sensitive to cold, and almost all attempts to grow them commercially in the eastern United States ended in failure. A new solution was required.

The most common source of etrogim, as a result, became the Caribbean. Much closer to America than the alternatives, Caribbean citrons were far cheaper and easier to access than those from the Ionian island of Corfu, which with the decline of the Corsican variety became the major provider of European etrogim. Caribbean citrons, principally from Jamaica (brought there by Columbus on his second voyage, in 1493), created a low-cost etrog market centered in the New World.

Yet Jamaican etrogim were yellowish-white and smoother and rounder than the Corfu ones. So were they really kosher? This question led to a vituperative halachic dispute among both Old and New World luminaries.

The Upside-Down Etrog

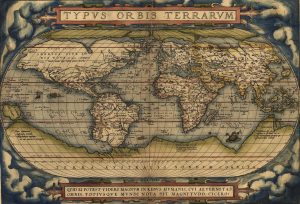

The most unusual response came in 1836 from one of central Europe’s leading rabbis, Yaakov Ettlinger. Mislocating the West Indies below the equator, he worried that “were we to take here [in Europe] the species that grew there [on the American islands], [we would hold it in] the opposite manner in which they grew” (Bikkurei Yaakov [Altona, 1836] 54b). In Europe, reasoned Ettlinger, the standard practice of holding an etrog with its protrusion or “pitom” upmost would mean that a Southern Hemisphere citron was in fact upside-down, violating the rule that all four species must be held and shaken in the manner in which they grow.

While dubious science, Ettlinger’s responsum fortuitously permitted those in the New World to continue using New World etrogim, while protecting European etrog producers from cheap New World competition. (Reprints of Ettlinger’s halachic works shifted the locus of this responsum from the West Indies to Australia to make him appear less geographically challenged. Etrogim aren’t native to that continent, however, and in 1836 its tiny Jewish community had yet to even build a synagogue.)

The Typus Orbis Terrarum, an eight-leaved map of the globe, was produced by Abraham Ortelius in 1570. It shows Australia as a vast, unknown territory, maps the equator (highlighted in red), and clearly places Jamaica (circled in red) in the Northern Hemisphere Courtesy of the Library of Congress Collection

The Typus Orbis Terrarum, an eight-leaved map of the globe, was produced by Abraham Ortelius in 1570. It shows Australia as a vast, unknown territory, maps the equator (highlighted in red), and clearly places Jamaica (circled in red) in the Northern Hemisphere Courtesy of the Library of Congress CollectionA few years later, Rabbi Solomon Hirschell of London reputedly outlawed Caribbean etrogim altogether. In his view, their unusual texture suggested that they had perhaps been grafted with lemons.

The citron’s extreme sensitivity to cold makes its tree a prime candidate for strengthening by means of grafting with lemon-tree cuttings. Grafted trunk of a Calabrian etrog tree in Corsica Photo: Blackdot

The citron’s extreme sensitivity to cold makes its tree a prime candidate for strengthening by means of grafting with lemon-tree cuttings. Grafted trunk of a Calabrian etrog tree in Corsica Photo: BlackdotStorm in an Etrog Box

In the 1840s, with the continued growth of the U.S. Jewish population and the immigration of a few well qualified rabbis, the debate over West Indian etrogim shifted to the New World itself.

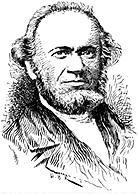

Rabbi Abraham Rice (1802–1862) fought a nine-year battle against Reform Judaism in Baltimore, eventually forming his own strictly Orthodox congregation while supporting himself as a merchant. Rice frequently contributed to Isaac Leeser’s Jewish monthly, The Occident

Rabbi Abraham Rice (1802–1862) fought a nine-year battle against Reform Judaism in Baltimore, eventually forming his own strictly Orthodox congregation while supporting himself as a merchant. Rice frequently contributed to Isaac Leeser’s Jewish monthly, The OccidentOn one side stood the first ordained rabbi to settle in the country, Abraham Rice of Baltimore. Firmly Orthodox, Rice staunchly defended West Indian etrogim in traditional halakhic terms: “These esrogrim are kosher, and there cannot be found any word against them in all poskim (halakhic decisors), Rishonim (medieval authorities), and Aharonim (later authorities)” (Abraham Rice, “American Citrons,” The Occident, May 1847, p. 117). Without these etrogim, he worried, American Jews would have none at all, as European shipments were unreliable and sometimes arrived after Sukkot. Rice’s diligent inquiries persuaded him that Caribbean etrogim were completely acceptable. Many of them, he learned, grew in the wild, so they were ungrafted. “All rumors set afloat against the kashrus of these esrogim,” he declared, “are founded in error and misinformation” (ibid.).

This lenient view was challenged by two learned Jews, Henry Goldsmith of New York and Isaac H. Levy of Cincinnati. Goldsmith insisted that the etrogim he had examined from the West Indies displayed all the signs of grafting. He cited Ettlinger’s ruling and corroborated his views with Hirschell in London. The latter confirmed that he indeed suspected West Indian citrons were grafted, for which reason “most communities in Europe do not purchase them” (Henry Goldsmith, “American Citrons,” ibid., June 1847, p. 157). Levy added that he personally had evaluated about five hundred Caribbean etrogim and determined that each had been crossed with lemons (“Note by the Editor,” ibid., July 1847, p. 212). He, Goldsmith, and other opponents of the Caribbean variety insisted that American Jews conform to European standards, even if that meant purchasing expensive etrogim from across the ocean.

Fruitful Investment

The British-trained, widely respected minister of the Danish West Indies colony of St. Thomas, Moses N. Nathan, offered the final word on Caribbean etrogim in a letter to Rev. Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia, the foremost champion of American Orthodoxy, who’d published the earlier correspondence and debates (but not Nathan’s response) in his monthly, The Occident. Having served in Kingston, Jamaica, Nathan knew the area and agreed with Rabbi Rice that citron trees grew wild there. Standard signs of grafting, he believed, applied only to carefully cultivated European etrogim, not to those grown in the Americas. Since Caribbean farmers devoted most of their time and arable land to more profitable staples, like sugar and coffee, they would have been foolish to “allow a laborer’s time to be wasted on the improvement of fruit trees” (Moses N. Nathan to Isaac Leeser, August 5, 1847, Gershwind-Bennett Isaac Leeser Digitization Project, University of Pennsylvania).

Nathan then reported his firsthand experiences with Jamaican citrons, harvested by slave labor:

Of Jamaica especially I can assert most positively that the citron grows in its original state, either where it was first planted, or where the wind has scattered the seed, and it has taken root. […] the citron and others of that family are useless except for making preserves, and grafting for that purpose would not pay […] citrons grow and rot on the trees[;] they may be had for the asking. The whole expense is confined to gathering, bringing them to town, packing, and freight to the States. One of our brethren in Jamaica used to send an annual supply to the synagogues by his slaves, free of cost[;] the present possessor of his estates permits any one to pluck citrons, who will send for them. (ibid.)

Illustration by James Hakewill from A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica (1824), showing slaves pausing near a waterfall on their way up into the hills near Kingston

Nathan concluded, in support of Rice’s opinion, that most local etrog exports were plucked from the wild and not grafted with lemons. As such, they were kosher.

Etrog as Metaphor

The ensuing decades saw etrogim from various places sold in the United States. Business boomed, largely because sugar prices dropped and candied citrons became a highly popular American treat. Which of these imports were actually kosher for use on Sukkot continued to be debated, but at the end of the day, much as local Jews could choose among different rites and movements and synagogues, they could now choose among etrogim from different locales: very expensive ones from Corsica or Corfu; cheaper varieties from the Caribbean; and, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, growing numbers of citrons from sunny California, where citrus of all kinds thrived.

The Hershey chocolate factory opened in Derry Church, Pennsylvania, in 1905, after the business had outgrown its premises in nearby Lancaster. Milton S. Hershey purchased the company’s first chocolate machine at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893

The Hershey chocolate factory opened in Derry Church, Pennsylvania, in 1905, after the business had outgrown its premises in nearby Lancaster. Milton S. Hershey purchased the company’s first chocolate machine at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 Interestingly, these three etrog sources reflected three different conceptions of America’s place in the global Jewish economy. Those who demanded European etrogim for Sukkot considered them the most reliable and believed that American Jews should follow the same standards and use the same ritual objects as their European counterparts; that the United States, in short, should be part of the European Jewish religious sphere and market. Those who endorsed West Indian etrogim, by contrast, located the U.S. within a vast New World Jewish religious economy – distinct from Europe – with suppliers in North and South America catering to its clientele’s every need. Finally, those who began developing the California etrog trade – which peaked in the final decades of the 19th century, sending etrog prices plummeting to a mere twenty-five cents – seem to have imagined the United States becoming an independent Jewish center, producing its own four species along with its own Hebrew books and rabbis.

Not one of these scenarios materialized, for several reasons.

First, American demand collapsed. Entrepreneurs such as William Wrigley and Milton Hershey produced cheap, popular candy products around the turn of the century, making candied citron obsolete. Other citrus, notably oranges, proved much more lucrative. In the early 1900s, etrog trees were ripped out to make room for more popular varieties. The California citron trade went bust.

Candied citron’s competitor. Ad for Wrigley’s “Juicy Fruit” chewing gum

Candied citron’s competitor. Ad for Wrigley’s “Juicy Fruit” chewing gumSecond, Caribbean citrons disappeared from the market. Many of the wild trees were burned or uprooted as plantations displaced forests. The Jamaican Jewish community, which once supplied etrogim to the United States, also dwindled in the 20th century; today it numbers around two hundred. Finally, trade with the Caribbean declined altogether, and citrons were purchased much more cheaply from California.

Third, and most important in the long term, steamships made it possible to import etrogim from the Land of Israel

Holiest of All

In September 1877, a scant decade after regular steamship service from New York to Palestine was inaugurated, newspapers in the Big Apple announced that J. H. Kantrowitz of 31 East Broadway had “imported from the Holy Land a choice lot of Esrogim” (“Town Topics,” Jewish Messenger, September 7, 1877, p. 6). The Jewish Messenger proclaimed this “the first time that Esrogim grown in the Holy Land have been sold in this city” and encouraged readers to offer Kantrowitz “liberal patronage” (ibid.). Etrogim from the Land of Israel were small and scrawny, lacking the visual appeal of those produced elsewhere. But whatever they lacked in appearance, they made up for in sanctity, justifying their hefty price tag.

As the etrog growers of the Holy Land were known to be pious Jews, no one could question their product’s halakhic fitness. In addition, money expended on these etrogim helped support Palestine’s struggling Jewish community (the Yishuv) as well as the nascent Zionist movement, making their purchase doubly commendable. Exotic at first, Palestinian etrogim steadily increased in sales and market share.

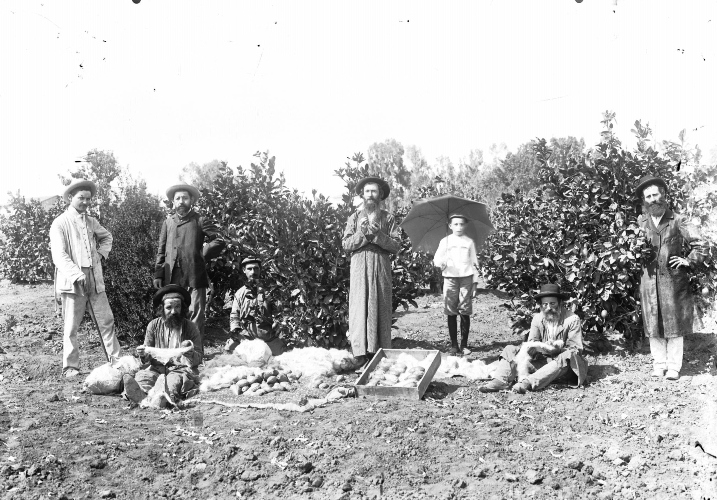

Citrons grown by God-fearing Jews in the land of Israel beat the competition hands down. Workers pose while harvesting etrogim in the Holy Land for the Pri Etz Hadar Society, circa 1905 Photo: Zadok Basan, Zionist Archives

Citrons grown by God-fearing Jews in the land of Israel beat the competition hands down. Workers pose while harvesting etrogim in the Holy Land for the Pri Etz Hadar Society, circa 1905 Photo: Zadok Basan, Zionist ArchivesMeanwhile, the reputation of Corfu’s etrogim, still popular among the most strictly Orthodox American Jews in the 19th century, rapidly declined. Lithuanian luminaries led by Rabbi Yitzhak Elhanan Spektor charged that Corfu’s non-Jewish citron dealers intentionally mixed grafted etrogim with ungrafted ones and raised prices, since they knew that Jews formed a “captive market.” Spektor, who encouraged many of his disciples to settle in American communities, called for a ban. Seeking to break the stranglehold of the island’s cartel, he and his allies promoted the development of new etrog sources, chiefly in the Land of Israel.

Then, in April 1891, the death of a young Jewish girl in Corfu prompted a well-publicized blood libel, resulting in massive anti-Jewish violence and the emigration of the majority of the island’s Jews. In response, many Jews boycotted Corfu products, etrogim included. Prominent members of the New York Jewish community, led by outspoken bookseller and Hebrew writer Ephraim Deinard, mounted a determined campaign against the Corfu citrons and in favor of their Palestinian competitors. Unable to offload etrogim on Europe’s Jews, Corfu’s merchants reportedly flooded the New York market to lower prices and drive out competition, which only fueled local Jewish ire.

A blood libel followed by a pogrom put the majority of Corfu’s Jews to flight, buttressing Rabbi Elhanan Spektor’s earlier calls for a ban to break the etrog cartel supplying the United States. The port of the Greek island, from which citrons shipped out, 1890

A blood libel followed by a pogrom put the majority of Corfu’s Jews to flight, buttressing Rabbi Elhanan Spektor’s earlier calls for a ban to break the etrog cartel supplying the United States. The port of the Greek island, from which citrons shipped out, 1890Corfu’s etrog growers never fully recovered. Instead, in the 20th century, orchards in Jaffa and Petah Tikva took the lead as part of a larger, Zion-centered restructuring of the global Jewish economy, which affected ritual objects of all sorts. For the better part of the last hundred years, a substantial majority of the etrogim sold in the United States have been imported from the Land of Israel – though they cost a lot more than twenty-five cents each.

When etrogim cost just twenty-five cents apiece. U.S. quarter, minted in 1882 Courtesy of USAcoinbook.com

When etrogim cost just twenty-five cents apiece. U.S. quarter, minted in 1882 Courtesy of USAcoinbook.comFurther reading:

Jane S. Gerber, ed., The Jews in the Caribbean (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, Liverpool University Press, 2014); Jonathan D. Sarna and Zev Eleff, “The Etrog Trade in the New World,” Warren Klein, Sharon Mintz, and Joshua Teplitsky, eds., Be Fruitful! The Etrog in Jewish Art, Culture, and History (Jerusalem: Mineged Press, 2021); Sakis Gekas, “The Port Jews of Corfu and the ‘Blood Libel’ of 1891: A Tale of Many Centuries and of One Event,” Jewish Culture and History 7 (2004), pp. 171–96.

Jonathan D. Sarna and Zev Eleff

Jonathan D. Sarna is Distinguished University Professor and the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University. He is also a member of Segula’s advisory board.

Zev Eleff is president of Gratz College, where he also serves as professor of American Jewish history