By Jews, for Jews. Leopold Cohn and clippings from his and his son’s missionary publications

By Jews, for Jews. Leopold Cohn and clippings from his and his son’s missionary publicationsThis article was published in issue 57 | Sivan/Tammuz 5781 | June 2021

The goal of converting Jews to Christianity is as old as the split between the two religions. Only the methods have varied, ranging from material incentives, intellectual persuasion, and cultural assimilation to the point of the sword or the flames at the stake. By and large, Protestant North America spared its Jews the persecutions they’d left behind in Europe and the Spanish colonies of South America, concentrating all its efforts on persuasion rather than coercion.

Although Jews have been in America since the early 17th century, the Protestant church began proselytizing among them only in 1816. With the beginning of the great influx of Jews into the U.S. in the late 19th century, missionaries targeted particularly the poor. Thus, as scholar Yaakov Ariel asserts: “Until the 1880s, […] missionary enterprises were small and sporadic […]. In the late 1870s, only one mission labored among the Jews in America” (Yaakov Ariel, Evangelizing the Chosen People: Missions to the Jews in America, 1880–2000, [Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000], p. 2). Later, however, the number of missions focused on Jews rose significantly, and dozens of such missions still operate today.

The upsurge in missionary activity in America since the late 19th century can be attributed to three factors: first and foremost, the great Jewish migration peaking between the early 1880s and the early 1920s), during which the number of Jews in the U.S. grew tenfold, exceeding 4.2 million by 1927; second, the spread of Dispensationalism, a school of Christian premillennialist eschatology founded in Britain in the 1830s, which gained popularity in the United States from the 1870s onward; third, the rise of Jewish nationalism beginning in the mid-19th century, culminating in the establishment of the Zionist movement in 1897.

Dispensationalism interprets the Bible as God’s plan for humanity throughout history, including the end of days. This plan requires the Jews’ return to the land of Israel before the Second Coming. The birth of Zionism thus increased Christians’ interest in their Jewish neighbors.

According to premillennialist eschatology, Jews are misguided but still have a crucial role to play in the redemptive process. Thus, in the early 1800s, Protestant missions in England and Scotland no longer sought to fully convert them. Rather, Protestants encouraged Jews to preserve their Jewish identity but accept Jesus and the New Testament. These converts were known initially as Christian Jews, and this type of mission was later dubbed Messianic Judaism. Europe numbered no more than a few hundred such Jews. In America, however, as of the late 19th century, Messianic Judaism was the leading form of mission to Jews, assuring them that embracing Jesus would actually enhance their Jewish identity, placing them on a higher spiritual plane than their brethren and even than born believers.

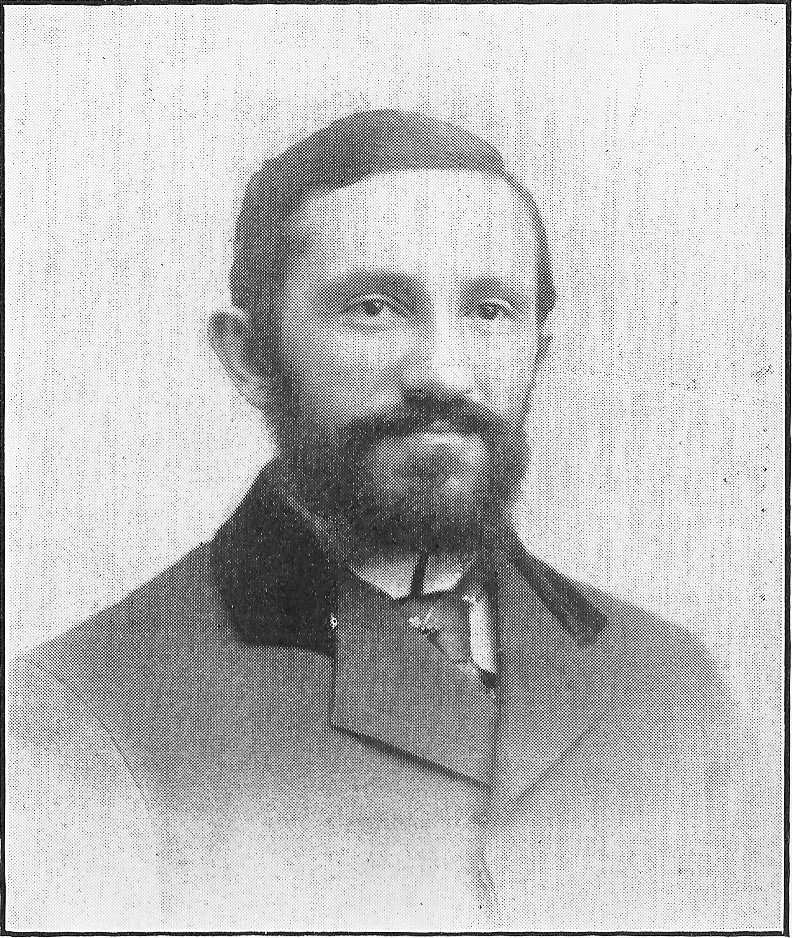

The man behind this revolutionary concept, which ultimately spawned the wildly successful Jews for Jesus movement, was himself a Jew: Eisik Leib Yosowitz, later known as Leopold Cohn.

A Hungarian in America

Eisik Leib Yosowitz was born in 1862 in the village of Brezna, in the Maramaros county of eastern Hungary. In this remote and sparsely populated region, most – including the Jews – eked out a living as farmers. The local Jews were known for their devout Hasidism and absolute obedience to their rabbis. Like most of the area’s Jewish children, Eisik Leib grew up in a Yiddish speaking environment and received a traditional Jewish heder education.

When the boy was seven years old, his father died, and after his bar mitzva, his mother sent him to the Hasidic yeshiva in the small town of Sighet, the county capital. Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, head of the yeshiva and chief rabbi of the town, was a Hasidic leader renowned for his zealousness. A few years later Yosowitz continued his studies in Hungary’s most prestigious yeshiva, located in Pressburg (today Bratislava, capital of Slovakia). There, according to his own testimony, he was ordained as a rabbi – a claim unsubstantiated by other sources.

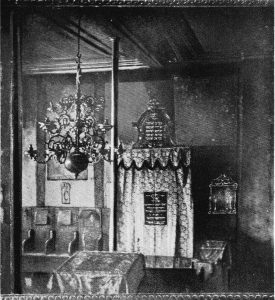

Eisik Leib Yosowitz studied at Hungary’s most elite Talmudic academies. The holy ark at Pressburg Yeshiva, from a book published in 1902

Eisik Leib Yosowitz studied at Hungary’s most elite Talmudic academies. The holy ark at Pressburg Yeshiva, from a book published in 1902After returning home, Yosowitz married Rosa Hoffman, daughter of a prosperous Jew from Apshitza (another small village in Maramaros), and the couple moved in with the bride’s parents. As was customary in those days if the groom was a Torah scholar, the bride’s father supported the newlyweds, allowing the young man to continue his studies. Unfortunately, Rosa’s father died a year later, obliging Yosowitz to take over the family business including management of the local inn. Given his above-average Talmudic knowledge, although he held no formal position, the local Jews regarded him as their highest rabbinical authority, consulting him on all religious matters.

In 1891, Yosowitz and his brother-in-law were accused of forging a deed to a piece of land belonging to one of their clients who had passed away without heirs. Yosowitz immediately fled the country to avoid trial, leaving behind his wife and their four children. He reached the United States in early 1892 after a lengthy journey and was warmly received by some of his friends and countrymen. Cohn later denied this version of events, claiming that theological doubts precipitated his emigration to America.

Yosowitz Becomes Cohn

Soon after his arrival, and failing to find a permanent job, Yosowitz encountered Herman Warszaviak, a Polish Jewish immigrant who had converted and become a successful missionary.

Herman Warszaviak, the friend who advised Yosowitz to convert to Christianity on arrival in New York

Herman Warszaviak, the friend who advised Yosowitz to convert to Christianity on arrival in New YorkHe convinced Yosowitz to follow in his footsteps, and on June 26, 1892, Yosowitz converted as well. Warszaviak then helped his friend obtain a scholarship to a Christian institution in Edinburgh, Scotland. When news of his conversion reached his relatives in Hungary, they excommunicated him. Though devastated by her husband’s transformation, Rosa was persuaded to join him in Edinburgh with their children, Benjamin, Joseph, Joshua, and Esther, and eventually they too converted.

Yosowitz excelled in his studies and was ordained a Baptist pastor, subsequently changing his name to Leopold Cohn and returning to New York with his family in October 1893. A few weeks later, Cohn established his own mission in Brownsville, naming it the Chosen People Ministry. Brownsville was one of New York’s largest concentrations of Jewish immigrants, most of whom lived in dire poverty and suffered discrimination. Although Cohn’s dubious past was exposed in the local Jewish newspaper, he won the trust and financial support of the Brooklyn chapter of the American Baptist Home Mission Society.

Since many missions were then targeting Jews, Cohn needed his own distinctive strategy. First, he adopted and expanded the idea of Messianic Judaism, which he had probably encountered in Europe, and which he preferred to “regular” conversion. Second, he invested equal time and energy preaching and fundraising among Christians and working with Jews.

Cohn’s mission provided medical consultations as well as used clothing and food packages donated by Christians. It also ran English-language classes and a sewing school where unskilled Jewish women were trained for employment in the garment industry’s sweatshops – virtually the only place where an uneducated woman who didn’t speak English could find work.

Many of the Jews arriving during the great migration period came without their extended families. Cohn invited these transplants to celebrate the Sabbath and Jewish holidays in a traditional atmosphere. Drawing on his rabbinical knowledge, he delivered eastern European–style sermons that sounded just like the ones they heard in synagogue back home. Having captured his audience’s attention, Cohn then gradually incorporated messianic messages. Unlike other missionaries, who persuaded Jews to trade their Jewish heritage for Christian traditions and values, he urged his listeners to embrace Jesus as the full realization of their Jewish identity. While his colleagues saw Jews as traitors and sinners to be elevated to the superior faith of Christianity, Cohn, as his ministry declared, regarded them as the chosen people.

To his Christian audience, he explained that Messianic Jews possessed an even loftier spiritual value than born Christians, given their relation to Jesus, who was also born Jewish. As such, he argued, only a converted rabbi, like himself, could convince Jews to accept Christ. Cohn cemented his links with the Christian community by publishing The Chosen People magazine, reporting on his activities and persuading Christians to contribute money and volunteer in his mission. This monthly became so crucial to the mission’s operation that it still appears today, more than 120 years after it began in 1895.

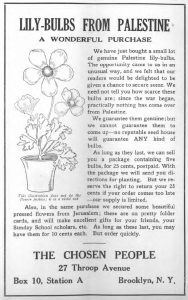

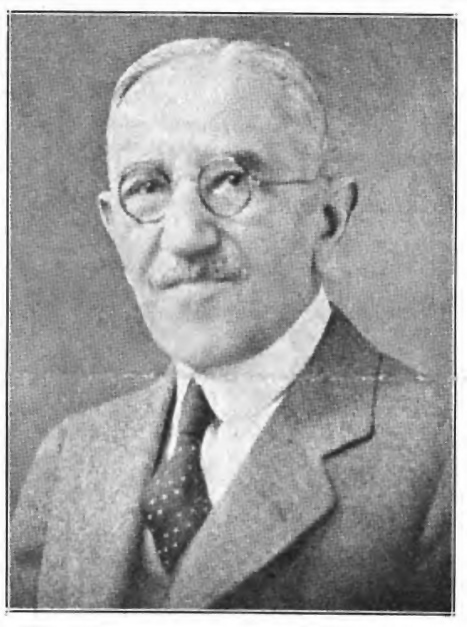

The elder pastor. Leopold Cohn in later years and a wartime ad for lily bulbs from Mandate Palestine, taken from his journal, The Chosen People

The elder pastor. Leopold Cohn in later years and a wartime ad for lily bulbs from Mandate Palestine, taken from his journal, The Chosen PeopleExpanding the Mission

In 1897, Cohen opened a branch in Williamsburg, home to many Hungarian Orthodox Jews who had moved there from Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His Williamsburg Mission to the Jews soon became the Chosen People’s most active station and, by the turn of the century, one of the busiest missions operating among Jews in the U.S. By the early 1900s, the mission boasted recreational programs for children – allowing their mothers to go out to work – as well as a clinic whose staff also made house calls.

Christian Baptists happily contributed to Cohn’s missionary cause. One wealthy benefactor even changed her bequest to an immediate donation, paying off the mortgage on the building housing Cohn’s Prince of Peace Mission in Williamsburg

Christian Baptists happily contributed to Cohn’s missionary cause. One wealthy benefactor even changed her bequest to an immediate donation, paying off the mortgage on the building housing Cohn’s Prince of Peace Mission in Williamsburg Cohn’s success made him many enemies. Notorious among Jews, he was seen even by some Christians as an exploitative charlatan. The Jewish leadership, however, found it difficult to take effective action against Cohn’s mission, as in Christian America – which harbored not a little anti-Semitic bias – such activity was not only legitimate but even welcome.

Cohn complained that on several occasions his workers faced threats and even violent attacks. Nonetheless, because the overall number of Jews who actually converted remained low even until the late 1930s, the Jewish community’s response was confined to the publication of a few booklets and newspaper articles and the distribution of posters and leaflets warning about the mission. Furthermore, Jews themselves were divided. The Orthodox felt that the larger Reform and Conservative communities posed a far greater danger than Cohn’s small group of converted Jews. At the same time, the non-Orthodox, who sought greater social integration, were reluctant to confront the powerful churches sponsoring such missions.

Notwithstanding his efforts to convert Jews, Cohn regarded himself as their protector. For example, in 1899, he asked the New York City education commissioner to remove such classics as Ivanhoe and The Merchant of Venice from the curriculum, as they portrayed Jews in a negative light. Two years later, when the Jewish community stood accused of not waving flags to mark the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt, Cohn explained that the ceremony had taken place during Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, when all the Jews were in synagogue.

With the rise of anti-Semitism in the early 20th century, Cohn delivered countless sermons reminding Christians of their historic debt to their “older brothers.” He pleaded with them to be more tolerant and not to offend, insult, or discriminate against poor Jewish immigrants. Like many other evangelicals, Cohn regarded Zionism and the return of the Jews to the land of Israel as the fulfillment of a messianic prophecy. He even fundraised among Christians for the Zionist movement and encouraged them to purchase Holy Land products.

Shadowed by the Past

In the early 1900s, members of Cohn’s wife’s family arrived in the United States. Having never forgiven him for converting, they exposed his real name and lack of ordination. The affair ended up in court, where Cohn was eventually forced to admit these and other facts about his former life.

In 1906 Cohn used some of the money he’d collected to purchase a large farm and country house in Connecticut. A year later, he received donations amounting to some $100,000 from wealthy Francis Huntley. When Cohn refused to share her gift with the Baptist church, its leaders accused him of violating their agreement and withdrew their sponsorship. Nevertheless, by virtue of this large endowment and his solid reputation, the missionary managed to maintain his operation and raise funds independently.

Cohn used his new wealth to purchase a plot in the heart of Williamsburg. There he built the House of the Prince of Peace, which served as the mission’s headquarters and activity center. In addition, he set up shop on Coney Island, where many Jews spent their summer vacations.

Of all Leopold’s children, only Joseph followed him into the clergy. After his ordination in 1908, Joseph became active in the mission, which evolved into a family business. Whereas his father spoke with a heavy Hungarian accent, Joseph was practically a native English speaker, having arrived in the United States as a child. This asset served him well in his many meetings with Christian communities across the country. The younger Cohn’s fundraising sermons extolled his father’s missionary work but also decried anti-Jewish discrimination, emphasizing the Jews’ contribution to the world in general and to the U.S. in particular.

In 1908, Leopold ran afoul of Philip Spivak and David Shapiro, two converted Jews who ran a mission in Brooklyn. To undermine his credibility, the pair visited Cohn’s putative missionary property in Connecticut, hoping to establish that it was used only by the family. Upon arrival, they confronted Joshua, Cohn’s third son, who pulled a gun on them. The feud was covered by the local press with great relish over the next few years.

Cohn fell into further disrepute following his wife’s death that year and his remarriage to a woman thirty-two years his junior. Few accepted his justification – that he’d married her only to provide a mother for his youngest, David.

All converted on arrival in America. The Cohn family: Leopold and his wife, Rosa, with children Benjamin, Joseph, Esther, Joshua, and youngest son David, born in the U.S.

All converted on arrival in America. The Cohn family: Leopold and his wife, Rosa, with children Benjamin, Joseph, Esther, Joshua, and youngest son David, born in the U.S.His wealth and personal ownership of some of the mission’s properties only added to the question marks surrounding him.

Hoping to restore his tarnished image, Cohn published The Story of a Modern Missionary to an Ancient People: The Autobiography of Leopold Cohn, a Missionary among the Two Million Jews of Greater New York. Subsequent editions toned down this bombastic claim, noting his preaching “only” to the 250,000 Jews of Brooklyn.

Further legal entanglements followed in 1913, when Hungarian Jewish missionary Alexander Neuowich threatened to sue Cohn after several women alleged he’d reneged on marriage proposals. Cohn reported Neuowich to the police, resulting in his arrest, and Neuowich then filed suit for wrongful imprisonment. His lawyer, Col. Alexander Bacon, produced several witnesses to Cohn’s sordid Hungarian past. A year later, Cohn was tried for forging his immigration papers, and a reward was offered to any who could shed light on his real identity.

In 1915, fellow Pressburg Yeshiva alumnus Samuel Freuder – who after coming to America become a Reform rabbi and later converted to Christianity – published his autobiography, A Missionary’s Return to Judaism. Freuder devoted an entire chapter to Leopold Cohn, his false identity, and the various scandals involving him.

These revelations drove the church to set up its own commission of inquiry, which released its report in 1916. The committee absolved Cohn of all guilt and encouraged Christians to keep funding his missionary activities. Yet his reputation was severely damaged, and the press continued criticizing him. In 1918, Philip Spivak successfully sued for slander, and then Col. Bacon published The Strange Case of Dr. Cohn and Mr. Joszovics, with Apologies to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, besmirching Cohn’s name once again. In 1920, bowing to pressure, he resigned as head of the mission and was succeeded by his son Joseph.

Away from the Public Eye

Groomed by his father for over ten years, Joseph was well positioned to run the mission. Father and son divided the work between them. As a Yiddish speaker well versed in Jewish texts, Leopold continued to take care of all “Jewish issues.” Joseph, on the other hand, expanded the mission into other Christian communities and, in 1924, renamed it the American Board of Missions to the Jews, suggesting the operation’s national rather than local nature.

Following in his father’s footsteps. Joseph Hoffman Cohn

Following in his father’s footsteps. Joseph Hoffman Cohn Leopold published new titles in Yiddish, reprinted his previous works, and brought out a new monthly, Shepherd of Israel. Unlike The Chosen People, which was aimed at Christian supporters, Shepherd was a Yiddish-English publication.

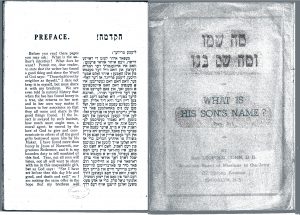

What Is His Son’s Name? Cohn produced this Yiddish-English manual after retiring from the American Board of Missions to the Jews (ABMJ)

What Is His Son’s Name? Cohn produced this Yiddish-English manual after retiring from the American Board of Missions to the Jews (ABMJ) It featured articles covering such Jewish-related issues as the Balfour Declaration, the appointment of Lord Herbert Samuel (a Jew) as the first British high commissioner of Palestine, and even the international convention of the ultra-Orthodox Agudath Israel movement in Vienna in 1923.

In 1930, in recognition of his lifelong missionary work, Leopold Cohn was awarded an honorary doctorate by Wheaton College, an evangelical institution in Illinois. He also publicly attacked fundamentalist preacher William Bell Riley for his global Jewish conspiracy theories.

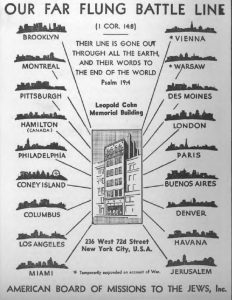

By 1932, Joseph had branches up and running in Philadelphia, Atlantic City, and Pittsburgh as well as in Lithuania. Two years later, there were others in Jerusalem, the Ukraine, and Poland. By the time Leopold Cohen died at the end of 1937, at age seventy-five, his mission was truly international. On the eve of World War II, many Jews in Europe converted to escape Nazi persecution; after the Holocaust, there were very few Jews left to convert. Yet in time Joseph revived his mission’s operations in Europe, with branches flourishing in Poland, Germany, Australia, France, and Latvia as well.

Though Cohn was perhaps the most prominent Jewish missionary, many continued his work. Poster celebrating the many ABMJ branches, with the flagship Leopold Cohn Memorial Building in the center

Though Cohn was perhaps the most prominent Jewish missionary, many continued his work. Poster celebrating the many ABMJ branches, with the flagship Leopold Cohn Memorial Building in the centerJoseph’s death in 1953 ended the Cohn family’s seventy-year leadership of the mission. In 1982, though, the organization reverted to its former name, Chosen People Ministries. Today, 125 years after its establishment, the mission is active in many countries and caters to hundreds of thousands, including a few hundred Jews.

Messianic Judaism Today

Although Cohn was very public about mission activities, donors, and contributions, he was less than forthcoming regarding the number of Jews he converted. In 1905, eleven years after the mission’s founding, Cohn claimed to have converted seventy-two of his brethren. Based on figures published in The Chosen People, by 1915, the total was still under two hundred. Later issues of the magazine indicate an annual conversion rate of ten to twenty. By Cohn’s death in 1937, then, his mission had converted some five hundred Jews. Given that during this roughly forty-year period, the mission targeted over a million Brooklyn Jews, this modest figure hardly qualifies as success. It also explains why Cohn failed to establish a congregation of Messianic Jews despite repeated attempts to do so.

Despite this failure and his numerous shortcomings – including his mendacity, use of the mission’s money for his own purposes, quarrels with associates, and mistreatment of women – Leopold Cohn was a visionary with outstanding capabilities. Like so many Jewish immigrants, he exploited whatever advantage he could in pursuit of the American dream of social and economic success. He was astute enough not just to replicate existing missionary methods, but to introduce a new tactic: Messianic Judaism. Coinciding with the rise of premillennialist Dispensationalism (commonly known as evangelical Christianity), Cohn’s teachings found a ready ear among these Christians and changed their fundamental conceptions regarding Jews.

Other missionaries realized the efficacy of this approach, and currently dozens of messianic movements with millions of supporters operate all over the world, and most have branches in Israel. For example, in 1970, Moishe Rosen, a former employee of the Chosen People, opened his own mission on the West Coast, originally called Hineni (“Here I Am”). Renamed Jews for Jesus, it was soon competing with Cohn’s organization as the most widespread mission targeting Jews.

Cohn’s flawed character notwithstanding, he must be credited with making Messianic Judaism the mainstream approach to missionizing American Jewry. While this innovation was fairly irrelevant to Jews, who dismissed all Jewish believers in Jesus as heretics and traitors, its impact on Christians was significant. Messianic Judaism taught them that however eager they were to convert Jews, Christians shouldn’t slander or discriminate against them. Rather, respect was in order both for them and for their expression of national identity through Zionism.

A wartime ad for lily bulbs from Mandate Palestine, taken from his journal, The Chosen People

A wartime ad for lily bulbs from Mandate Palestine, taken from his journal, The Chosen PeopleToday, the State of Israel benefits considerably from the evangelical support fostered by Cohn and a few of his contemporaries, creating a welcome counterweight to the intensifying atmosphere of political anti-Zionism current in ever-widening circles.

The elder pastor. Leopold Cohn in later years

The elder pastor. Leopold Cohn in later years Milestones in Christian Missionary Activity among American Jews

1699 – first attempts to convert Jews in North America

1816 – first societies proselytizing Jews set up in New York and by women in Greater Boston

Jewish missionary Joseph Samuel Christian Frederick Frey arrives in America from London

First Jewish books refuting the arguments of Christian missionaries

1820 – American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews founded 1823–25 – American Jews respond with the first Jewish periodical, The Jew, published by Solomon Jackson in New York

1880 – Jewish mass migration to America begins

1885 – Hebrew Christian Church established on New York’s Lower East Side

1890 – Hope of Israel mission set up on the Lower East Side by a Jewish convert to Christianity

1894 – Leopold Cohn opens mission in Brownsville, Brooklyn

1895 – Cohn launches a journal, The Chosen People

1897 – Cohn’s second mission opens, in Williamsburg

1915 – Hebrew Christian Alliance of America founded

1920 – Joseph Cohn takes over from father Leopold, expanding his ministry and renaming it the American Board of Missions to the Jews

1937 – Leopold Cohn dies, leaving behind ten missionary branches in the U.S., six in Europe, and one in the Holy Land

1953 – Joseph Cohn dies; Harry Pretlove takes over

1967 – Young Messianic Jewish Alliance founded

1970 – Moishe Rosen resigns from Cohn’s ministry to set up his Hineni mission in San Francisco, changing its name to Jews for Jesus in 1973

1986 – International Alliance of Messianic Congregations and Synagogues founded

1988 – Cohn’s organization reverts to its original name, Chosen People Ministries

1990 – One for Israel ministry and its Israel College of the Bible founded in Netanya, Israel

2021 – hundreds of missionary organizations target Jews in Europe, the U.S., and Israel