A Rude Awakening

On February 5, 1840, Father Thomas, a Capuchin monk living in Damascus, disappeared along with his servant. Local Christians, with the active support of the French consul, accused the Jewish community of his abduction and ritual murder. Several Jewish leaders were imprisoned and tortured for months. Those who survived were convicted of the crime. European newspapers reported this resurrected medieval blood libel extensively, and the tale was widely believed, or at least considered plausible.

Drawing of the alleged ritual murder in Damascus, from an Arabic book published at the time. The volume pictured is titled “The Talmud”

Horrified to discover that their supposedly enlightened European neighbors took the malicious accusations seriously, French and British Jews sent a joint delegation eastward, led by British philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore and French lawyer Adolphe Crémieux.

In Alexandria, the delegates appealed to Muhammad Ali, pasha of Egypt, for a fair trial. The pasha had conquered Greater Syria by rebelling against the Ottoman sultan Mahmud II, and was facing attack from the European empires that sought to wrest the Levant from his grasp. Given this political pressure, combined with Montefiore and Crémieux’s painstaking efforts, Ali pardoned the condemned, albeit without acquitting them. Montefiore and Crémieux returned to Europe triumphant and were feted by its Jewish communities.

Thoroughly documented, the Damascus Affair has resonated powerfully in Jewish historiography. One example is Prof. Jonathan Frankel’s masterful The Damascus Affair: “Ritual Murder,” Politics, and the Jews in 1840. Some even consider the episode a turning point in Jewish history, deeming it the beginning of global Jewish solidarity.

From One Woman to Another

Translations of the interrogations and of correspondence between European consuls have preserved the suspects’ testimonies and statements made by their families, but between the interrogator, the translator, and the torture chamber, the true voices of the accused can barely be heard. A letter recently discovered in the Central Archives in Jerusalem shifts our perspective to the prisoners’ wives, giving us a rare glimpse of their experiences and role in the Damascus Affair.

Sources tend to dwell in graphic detail on the unbearable tortures endured by the prisoners, but their wives suffered as well. One such victim was Oro (or Ora, as the interrogation protocols refer to her), whose husband, Moses Abulafia, scion of a famed rabbinic dynasty, confessed to the accusations, converted to Islam, and became a key witness for the prosecution. Oro was beaten during her husband’s questioning and forced to watch his torture. Joseph Lañado’s wife, who became his widow as a result of the brutal interrogation, claimed that the French consul attempted to extort sexual favors from her as a condition for helping her husband, and similar reports involve the daughter of another of the accused, David Harari. Other women were made to testify before various interrogation committees, where they displayed incredible courage and will.

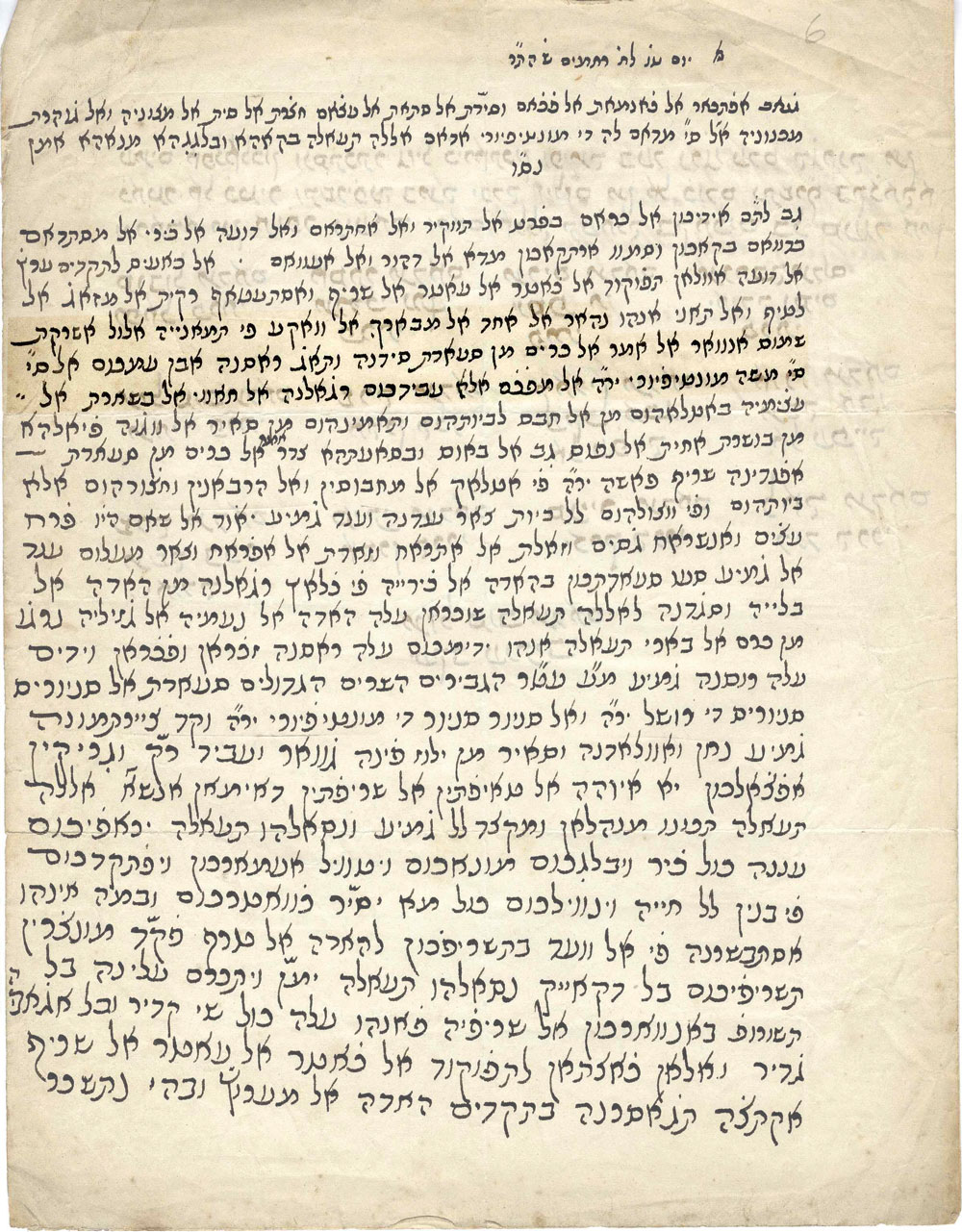

After the affair was resolved, the women involved wished to thank their European benefactors. The letter below was composed by the wives of the thirteen surviving prisoners. Written in Judeo-Arabic, using Oriental-style Hebrew letters, it is addressed to Lady Judith Montefiore, who had accompanied her husband on his mission of mercy.

The writers praised their saviors in lavish terms, proclaiming that:

The light of our eyes, the crown of our heads, the great, noble, and honorable lords Saadat El Señor de Rochelle [Rothschild] and the honorable El Señor de Montefiore” will never be forgotten.

… that day, that blessed Sunday, 8 Elul, the light shone forth, thanks to the honorable concern expressed by our great lord and master, your cousin the señor, the exalted, distinguished Señor Moses Montefiore, … [culminating in] the joyful tidings of [our husbands’] release from prison to their homes.

Order of Signatures

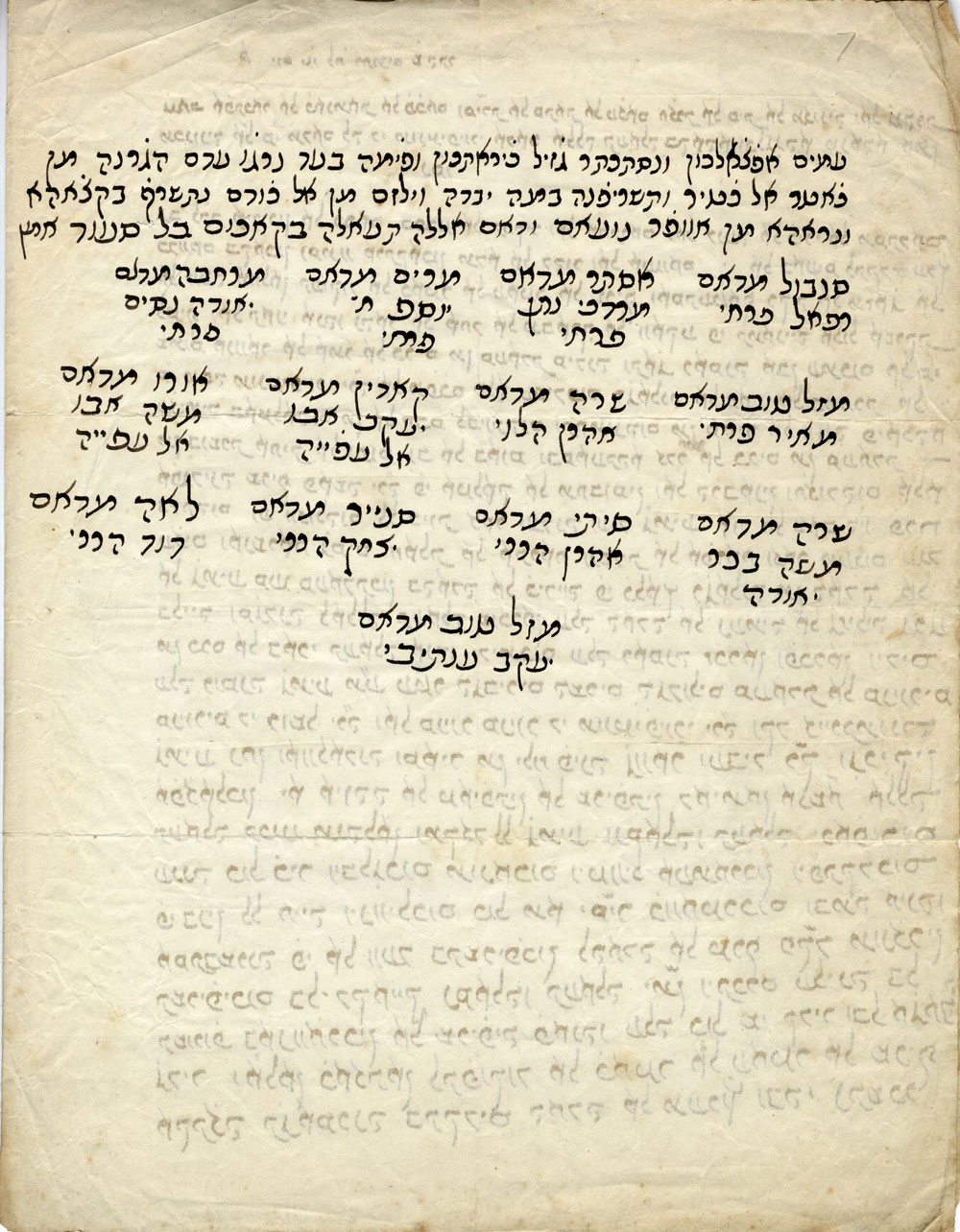

The order of signatures reflects friction within the Damascus Jewish community, which had also sparked mutual accusations during the trial. The signatures of the Farhi family, the wealthiest Jewish clan in Damascus, head the list. The women of the rival merchant family of Harari signed at the end. Between these signatures come those of the rabbis’ wives and the middle-class women – including “Oro, Madam Moses Abu el Afia,” the wife of the apostate. Last on this list is Mazal Tov, wife of Chief Rabbi Jacob Antebi.

Signatures of the women from the Damascus Jewish community at the end of their letter to Lady Judith Montefiore

The date described in the letter as the day “the light shone forth” – when the imprisoned husbands were released and the accused who had gone into hiding and been condemned in absentia could finally reappear – corresponds with that appearing in the foreign consuls’ reports. The letter was written on “the fifteenth day of the month of mercy” (the Hebrew month of Elul), approximately one week after the prisoners were released. A letter penned by the French consul to his superior at the Beirut consulate makes bitter mention of the Jews’ celebrations, including a party held around that date in the Austrian consul’s garden, attended by the released prisoners and their wives, among others. Perhaps this was the forum at which the women decided to compose a letter of gratitude to the wife of their savior – from one woman to another.

Thanks to Dotan Arad for his translation

from Judeo-Arabic

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (http://cahjp.huji.ac.il) rescues, restores, and preserves historical documents concerning the Jewish people from communities worldwide, from the

Middle Ages to the present