Sara Rosenberg’s flight from British Mandate authorities passed through hospitals and prisons all over Palestine. Who was this underground fighter, and what did she leave behind? // Tamar Hayardeni

Warning: this column concerns one of Haifa’s ugliest buildings – notwithstanding its breathtaking view of the lush Carmel Forest. Despite the depressing boxiness of Bnai Zion Medical Center (formerly the Rothschild Hospital), the thrilling tale that climaxed within its walls makes it worth a visit. And you can actually see where it happened – as long as you know where to look.

Fields of Bethlehem

The yarn begins toward the end of 1946, less than five kilometers from the hospital as the crow flies, at 82 Atzma’ut (Independence) Street, in the Haifa Bay area. The Zionist underground’s anti-British activities were at their peak (including operations initiated by both the mostly Labor Zionist Palmah and the Revisionist Irgun) when a striking Irgun agent named Sara Rosenberg made off with a bunch of highly classified documents from the British Investigative Headquarters, then located at that address.

What she wouldn’t do for freedom. Sara Rosenberg Livni, Irgun (Etzel) fighter and mother of Tzipi Livni

Rosenberg was en route to the Revisionist Zionist headquarters in Tel Aviv when her bus was stopped by a British army jeep. Someone had informed on the shocked young lady, and she was extracted from the vehicle by two burly policemen and placed under arrest. Sara barely concealed the incriminating evidence on her person before being dragged off to the Zikhron Yaakov police station.

The British were sure they had an airtight case against her, but Rosenberg stayed one step ahead. A bathroom break before the interrogation seemed perfectly reasonable, enabling her to flush away the documents. Unfortunately, the cops were prepared for such tactics, and a net had been strategically placed at the base of the toilet bowl. Soaking though they might be, the papers now clinched her guilt.

Sara’s trial was short and to the point, landing her in the British women’s prison in Bethlehem. But this fearless fighter had no intention of quietly serving out her sentence. As she later recalled:

One of the first questions I asked myself on arrival at the Bethlehem jail was “How do I get out of here? How best to escape back to my comrades in arms?” The answer was frustrating; my fellow prisoners, already familiar with conditions, told me security had been reinforced after a recent successful escape [see ”By the By,” p. XX], with extra barbed wire stretched around the perimeter and armed guards on the roof to foil any further attempts. (Anschel Shpilman, ed., How We Escaped to the Front – 36 Daring Escapes from the British Authorities by Members of the Zionist Underground [Tel Aviv 1979], pp. 263–4 [Hebrew])

Helicopter Heist

To make matters worse, the jail was situated in the midst of Bethlehem’s hostile Arab population. Even if Rosenberg made it out of prison, how was she to avoid being lynched outside its gates? Adding to her predicament was her own volatile temperament – she’d already slapped a British officer who’d annoyed her on arrival. As a result, she’d been transferred to the jail’s maximum security section, whose prisoners were permitted to exercise only on the roof rather than in the yard.

Yet Sara saw this restriction as an advantage. She’d just read about the invention of the helicopter, and it seemed to her the perfect getaway vehicle. A few Revisionist operatives merely had to hijack a British army chopper, fly it to Bethlehem, land on the prison roof, and whisk her – and any other inmates they could fit in – off into the sunset.

For months, Rosenberg and her partners in crime secretly gathered reconnaissance information. They paced the roof to measure its length, checked the number of guards posted there at any given moment, and noted exactly when the watchmen came on and off duty. Somehow the women smuggled all their findings out to Eitan Livni, a Revisionist activist who’d recently extricated himself from the British jail in Acre and was serving as the Irgun’s director of operations. The plan was flawless apart from one problem: unbeknownst to all those planning the breakout, the British forces in Mandate Palestine had no helicopters.

Eventually realizing that her plan wouldn’t work, Sara sought other escape avenues. After the Arab riots following the UN vote partitioning Palestine on November 29, 1947, she began protesting that holding Jewish women prisoner in the middle of an Arab population center was too dangerous. Any minute, a violent mob could storm the prison and attack or even kill its inmates.

When her requests for transfers were ignored, Rosenberg organized a sit-in; the women refused to return to their cells. In the ensuing commotion, she broke into the administrative offices and set them on fire, but not before grabbing the keys.

By now, the Bethlehem prison director had had enough. The “monster” and all other Jewish prisoners were to be moved elsewhere at the first opportunity.

Imaginary Invalid

On December 28, Bethlehem’s female Jewish detainees arrived at the Atlit detention camp for illegal Jewish immigrants, near Haifa. Security was a little looser at this installation, and its surrounding beaches were a refreshing change from grimy Arab Bethlehem, but Sara was still under close observation. Aware that a regular breakout didn’t stand a chance, she set to work on something more sophisticated; she’d pass herself off as deathly ill. Hospitalization would be her ticket out.

Reading up on disease symptoms, Sara discovered that an injection of hot milk could cause fever and seizures. A Jewish medic armed with a syringe was smuggled into the camp, but the effect of the injection was completely unexpected:

At first I felt nothing, but I was soon afflicted by such severe dizziness that I thought my end was near and I’d be leaving Atlit on a dead man’s stretcher. (ibid., p. 265)

Nonetheless, the detention camp’s chief officer decided that Rosenberg’s condition didn’t justify the risk of transfer to a medical facility.

The dizzy spells gradually subsided, but Sara wouldn’t give up. After a sleepless night, she dragged herself to the dining hall in the morning and feigned appendicitis, screaming in agony. Her histrionics did the trick, and she was immediately evacuated.

An ambulance deposited Rosenberg at the Haifa Government Hospital, today the old wing of Rambam Hospital and located in the heart of what was then an Arab neighborhood. Security was tight, and as if that weren’t enough, the imaginary invalid was rushed straight to the sixth floor for emergency surgery!

With no choice, Sara confessed her ruse and asked to return to Atlit. But the doctors dismissed her protestations as a bad case of pre-operative nerves and insisted on performing the procedure.

The patient demanded that she at least be operated on in a Jewish hospital. After all, who could trust a British doctor? Only a year ago, one Irgun operative had died on the table! (He’d been three-quarters dead on arrival, but no matter.) She told the medical team in no uncertain terms that they were not to come anywhere near her.

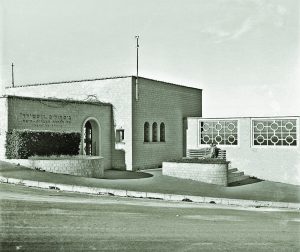

Exhausted, the staff gave up and packed her off to the Rothschild Hospital, in Haifa’s Hadar Carmel neighborhood. Finally breathing easier, Rosenberg took stock. She couldn’t expect help from the hospital personnel, and the guard outside her room wasn’t going anywhere. But Rothschild was only one story high, and the area was Jewish…

Under the very noses of the staff preparing to operate, the patient leapt off the bed and – with Olympic agility – out the window! In a twinkling, she’d disappeared in the crowded alleys of Jewish Haifa.

The British were beside themselves; the sergeant at the door was demoted to private, and they spent days searching for the fugitive – to no avail. The bird was flown, and all that’s left of Rosenberg’s escape is an ugly hospital in the middle of Haifa.