When I had attained the age of 20, I began to study the Zohar and the Lurianic writings. [According to the Talmud] whoever wants to purify himself receives the aid of Heaven; and thus He sent me some of His holy angels and blessed spirits, who revealed many mysteries of the Torah to me. That same year, energized by the visions of the angels and the blessed souls, I was engaged in a prolonged fast during the week before the feast of Purim. I locked myself in a room in holiness and purity, and as I tearfully recited the penitential prayers of the morning service, the spirit came over me. My hair stood on end, and my knees shook. And I beheld the merkava [divine chariot], and I saw visions of God all day long and all night. I was vouchsafed true prophecy like any other prophet, as the voice spoke to me, beginning with the words “Thus speaks the Lord.” With utmost clarity my heart perceived toward whom my prophecy was directed… and only then did the angel permit me to proclaim what I had seen. I recognized that he was [the] true [Messiah]…. And indeed the angel that revealed himself to me in my waking vision was a genuine one, and he revealed awesome mysteries to me.

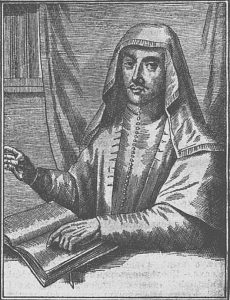

This amazing vision was recorded in 1667 by a mysterious young kabbalist whose name later became famous throughout the Jewish world: Nathan ben Elisha Hayyim Ashkenazi – or, as he is better known, Nathan the Prophet of Gaza (1643–1680).

“This is the likeness of the man who, in his gross impertinence, declared himself Messiah and caused this grievous madness and folly,” wrote Thomas Konen, in whose book, published circa 1669, the portrait of Nathan of Gaza appeared

Who was this man? How did he set one of the greatest revolutions in Jewish history in motion? From where did he draw the skill and power to sweep the Jewish masses – along with their leaders, magnates, rabbis, and kabbalists – so that they burned with belief in a messiah who heralded the end of history?

Explosive Energy

A close disciple of the well-known halakhic authority Rabbi Jacob Hagiz of Jerusalem, Nathan was considered a rare prodigy. His days and nights were spent in endless study, and he engaged in fasting and self-mortification to purify his soul.

At age 20, once he had married, he entered the gates of hidden wisdom. Within two years he had mastered the Zohar and the writings of both Rabbi Moses Cordovero and Rabbi Isaac Luria (the Ari). As soon as he entered the Pardes, the realm of mysticism, his soul exploded. The resulting spiritual energy transformed him and his self-image; he became someone else, something else.

In addition to his powerful spirituality and his daringly original religious conception, Nathan had other strengths. His great concentration and persistence enabled him to engage in intensive activity for extended periods. He had tremendous willpower. He was eloquent both in person and in writing. He was systematic. Most important, he had rare interpersonal skills. People felt he could read their souls, and they were captivated by his charm.

Following his purported revelation and prophecy, Nathan began “rectifying souls.” He revealed his acquaintances’ darkest secrets, their innermost thoughts, and led them to repentance. Raphael Joseph Hajilibi – Egyptian minister of finance, governor of the Jewish community in Egypt, and a scholar in his own right – sent rabbis to examine the young kabbalist. They too were enchanted by his knowledge and spiritual power, and joined him.

One of those who traveled from Egypt to see Nathan was a scholar of some 40 years of age, a man of crushed spirit, named Shabbetai Tzvi. He arrived in Iyyar 5425 (1665) “seeking repair and respite for his soul.” But “when our master, Rabbi Nathan, saw him, he prostrated himself before him and asked his forgiveness for not having become his disciple when he first went down to Egypt, and announced that he had an extremely great soul.”

Rising and Falling

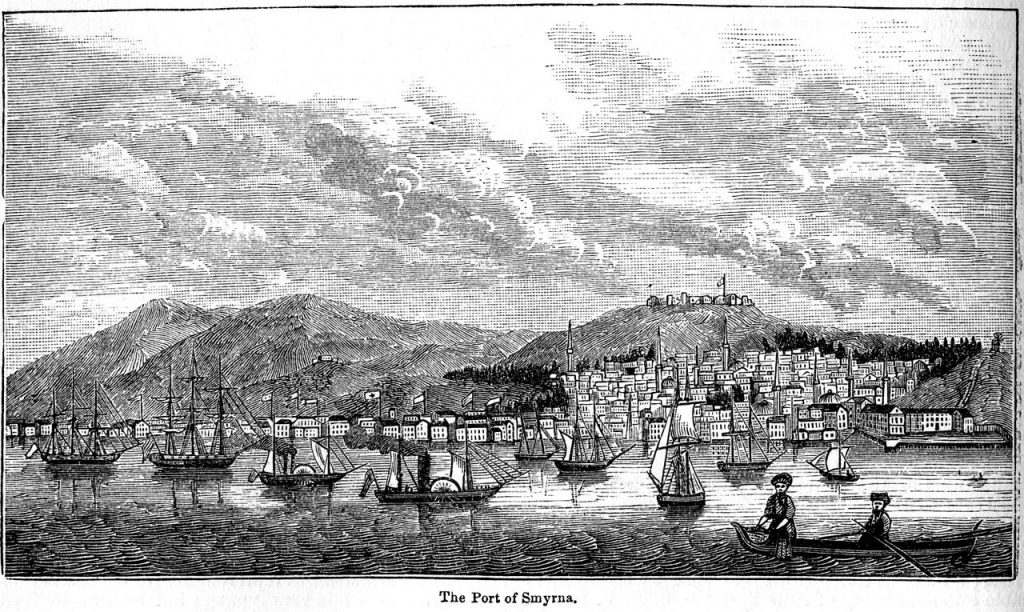

In 1626, on the Ninth of Av – a date traditionally associated with the birth of the Messiah – Shabbetai Tzvi was born in Izmir, once of the largest and most magnificent Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire. He studied under rabbis Isaac di Alba and Joseph Escapa and apparently was ordained himself at the age of 18. He began studying Kabbala independently, however, without teachers, focusing on the early kabbalistic works – the Zohar and Sefer Ha-kaneh – rather than on the Lurianic Kabbala accepted in his day.

Until the age of about 20, Shabbetai led a normal life. But when he married his first wife, he began behaving strangely. Shortly after the wedding, his father-in-law complained to a rabbinic court that the groom was avoiding his wife. Following this claim, Shabbetai divorced her. A few months later he remarried, but this wife received similar treatment. Not surprisingly, this marriage, too, ended in divorce.

Early reports of Shabbetai’s peculiar behavior suggest that he was bipolar, or manic-depressive. Periods of ecstasy and fervor, accompanied by a sense of mission and commitment, gave way to bouts of mohin de-katnut (“restricted consciousness”), seclusion, melancholy, and depression, in which he felt himself pursued from both within and without.

In 1648, amid the terrible Khmelnitsky pogroms – and increasing expectations of the Redemption – Shabbetai Tzvi heard an inner voice: “You are the Redeemer of Israel!” it declared. “I swear by my right hand and strong arm that you are the True Redeemer, and there is no other!” Initially, no one took him seriously, but then his behavior took a dramatic turn: he would pronounce the Tetragrammaton (the four-letter name of God uttered only in the Holy Temple) in the synagogue; he attempted to make the sun stand still at noon, as Joshua had done, by use of holy names derived from practical Kabbala; and he committed various transgressions, claiming they were actually mitzvot. By 1651, the rabbis of Izmir – headed by Rabbi Joseph Escapa – began to lose patience with his strange behaviors, and in 1654, they expelled Shabbetai Tzvi from the town.

A Fish in a Cradle

Shabbetai moved to Salonika and continued his strange practices. In one particularly outrageous episode, he erected a wedding canopy, appointed witnesses, and took a Torah scroll as his wife. He was expelled from Salonika as well, and in 1658 he reached the capital, Constantinople (Istanbul). There too he conducted bizarre ceremonies, such as placing an enormous, decorated fish in a baby’s cradle as a sign that the approaching Redemption would take place under the sign of Pisces. Flogging and excommunication at the hands of the local rabbinical court only made matters worse. Time lost all meaning for him as he celebrated all three annual festivals – Sukkot, Pesach, and Shavuot – within a week. Later he “received” a new, messianic Torah, which sanctified sin and even required that a benediction be recited prior to transgressing: Barukh… matir issurim, “Blessed be He… who permits the forbidden.”

Shabbetai Tzvi returned to Izmir, then departed for Egypt, where he tied the knot again, this time with Sarah of Ashkenaz, a former prostitute bent on marrying the Messiah. He chose her to fulfill the divine command to the prophet Hosea, “Go, get yourself a wife of whoredom.” In 1662, Shabbetai arrived in Jerusalem, where he cloistered himself and fasted from one Sabbath to the next. Sometimes he would embark on lonely journeys into the Judean desert. About two years later, Jerusalem’s Jewish leaders sent him to raise money from the Jewish community in Egypt.

Shabbetai Tzvi arrived in Egypt and succumbed once again to depression. Word of Nathan of Gaza reached the Jews of Alexandria, and Shabbetai traveled to see him, seeking relief for his tormented soul. Instead of a remedy, Nathan informed him that his lofty soul needed no repair, since he was the Messianic king himself.

The Coronation

In his depression, Shabbetai rejected these tidings, but he did agree to set out with Nathan to visit the tombs of the forefathers in Jerusalem and Hebron. En route, the two became extremely close. Shabbetai told Nathan everything that had happened to him since childhood, including his periods of enlightenment and despair and his expulsion from his birthplace. For Nathan, these stories meshed with his own concept of the torments through which the Messiah would be purified, and with his vision of the divine chariot, later detailed by Sabbatean leader Moses Piniero:

He would see something like a pillar of fire before him, and sometimes he would see something like the face of a man, and he also knew the quality of the soul speaking with him…. He saw all aspects [of Creation] in order, the chariot and the face of our master and king, may his glory be exalted [a reference to Shabbetai Tzvi].

Nathan and his protégé returned to Gaza before Shavuot, whereupon a remarkable event awed the local scholars. During the festival’s traditional all-night Torah study, Nathan fainted, falling to the floor in convulsions. A spirit seemed to speak from his throat: “Take heed of my friend Nathan, and obey his words; take heed of my friend Shabbetai Tzvi. If only you knew the praises of Rav Hamnuna Sava, ‘And the man Moses was exceedingly humble,’ for Shabbetai Tzvi is worthy of being king over Israel!”

The Galatta Tower, already a landmark of Istanbul when Shabbetai Tzvi visited the city, was built in the 14th century. Etching by Paul Lucas, 1720

Shabbetai came out of his depression, and his admirers testified: “One the third day following that utterance of Nathan the prophet, enlightenment and the holy spirit returned to our master in double measure, and his spirit revived.” Nathan revealed an ancient letter, supposedly written by Rabbi Abraham, “a great scholar in the days of Rabbi Judah Ha-hasid, who locked himself away for forty years and ate [even] ordinary food in purity, who would not look upon any human face, and who would expound the secrets of the Torah.” The letter stated:

Behold, a son is born to Mordechai Tzvi in the year 5386 [1626], and he shall be called Shabbetai Tzvi, and he shall vanquish the great dragon and take the power of the serpent bariah and the power of the serpent akalaton, and he is the true Messiah. And he shall come unarmed to war, until the ass shall climb the ladder and his kingdom shall be forevermore, and there shall be no Redeemer of Israel other than he.

The letter depicts the terrible torments and trials that the Messiah will undergo, as well as the great opposition of his contemporaries, who will “revile and curse him, but these are the mixed multitude, the children of Lilith.” Also described are the sexual temptations he will face and the powerful, impure “husks” that will attempt to subdue him.

Sabbateanism picked up speed. Shabbetai donned rings inscribed with holy names; he cast a bronze serpent, similar to that which Moses had made (the Hebrew word nahash, serpent, containing the same letters as Mashiah); and he and his prophet imposed severe penances and fasts. He also abolished the fast of the seventeenth of Tammuz, instead reciting the Great Hallel, “for the time of the beloved has arrived, the groom has emerged from his canopy, and so within the houses of Israel there shall only be joy and happiness.” The vast majority of the Jews in Gaza and Hebron accepted his rule unquestioningly and called themselves “Believers.”

“Whoever Kills Him Will Be Blessed”

Shabbetai Tzvi recruited twelve sages from Gaza to escort him to Jerusalem and offer sacrifices at the site of the Temple – outraging most of the city’s rabbis – and appointed Rabbi Jacob Najjara, the rabbi of Gaza, as high priest. But most scandalous in the eyes of the rabbis was Shabbetai’s feeding his followers forbidden animal fats (helev), the punishment for which is karet, spiritual excision. It seems that he intentionally chose transgressions providing no particular enjoyment – since the forbidden helev tastes the same as permitted fat – to emphasize that he had no ulterior motive, only a desire to uphold the new Torah.

Understandably, some of the most important rabbis in Jerusalem excommunicated Shabbetai Tzvi. Among them were Rabbi Jacob Zemah, a most prominent Lurianic kabbalist, and Rabbi Jacob Hagiz, Nathan of Gaza’s former teacher. They wrote to the rabbis of Izmir: “The person expounding these innovations is a heretic, and anyone who kills him will be considered to have saved numerous souls; indeed, the hand that rises up to slay him will be blessed in the eyes of God and man.” Interestingly, the Jerusalem rabbis’ anger was directed not principally at Shabbetai’s messianic pronouncements, but at his public transgressions.

However, the excommunication was no match for the masses’ tremendous yearning for a new reality. Nathan of Gaza synthesized this upsurge of repentance and mortification with the traditional messianic longing, constructing a complete paradigm that explained Shabbetai Tzvi’s strange actions as part of a hidden divine plan.

Nathan was in an amazingly spiritual state, receiving visions daily. On 25 Elul 5425 (1665), he heard a “herald from the Heavenly Academy announcing: In one year and a number of months, the Messiah, son of David, will appear in the world!”

Public Ecstasy in Izmir

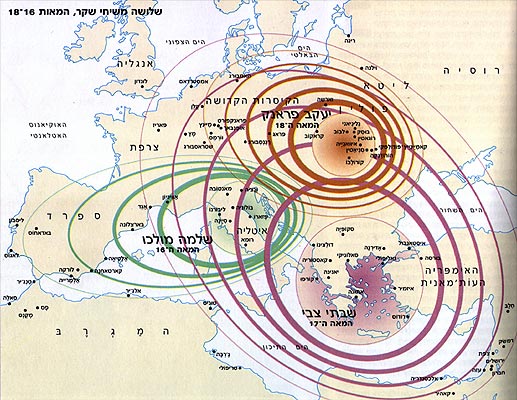

At the beginning of 5426, a newly depressed Shabbetai Tzvi resumed clandestine activity in Izmir. In the meantime, news of the Messiah’s appearance spread like wildfire throughout the Jewish world. The rumors spoke of the Ten Tribes’ surfacing in various locations – in Persia, Saudi Arabia, and the Sahara. Christian scholars, who looked forward to the millennium, when Jesus would return and reign for one thousand years, believed the reports, and circulated them among their own communities, hoping that a Jewish messianic awakening would lead to acceptance of Jesus.

A few months later, an epidemic of mass prophecy hit Izmir. Men and women alike fell into an ecstatic trance and were revealed as “prophets speaking great things.” This phenomenon spread to Aleppo, Constantinople, and Safed, where “ten prophets and ten prophetesses” were revealed. In Safed, too, the great kabbalist Rabbi Benjamin Halevi joined the movement.

The masses slept in the streets and marketplaces and undertook stringent penances, including weeklong fasts, followed by feasting. Legends told of miracles: a fiery cloud interposing itself between the prophet and his followers, and an angel speaking therefrom; the immanent revelation of the purifying ashes of the biblical red heifer; and, most astounding of all, churches sinking into the earth.

This star of David was found carved into the stone wall of the house in Ulcini, Montenegro, to which Shabbetai Tzvi was exiled in 1672

During the first week of Hanukka, Shabbetai Tzvi came to the synagogue in Izmir in regal garb “and there began to recite prayers and hymns, and made a great celebration.” On the following Sabbath, accompanied by an enormous entourage, he appeared at his opponents synagogue. He broke down the door with an axe, delivered strange sermons, read the Torah from a printed text, and called women to the Torah. He reviled the “heretical” sages and began appointing his brothers and close associates to various positions associated with the Redemption: high priest, sultan of the Turkish kingdom, Roman emperor, and so on. Shabbetai then opened the holy ark and sang a Spanish love song about the emperor’s daughter, subsequently expounding on the song’s hidden meaning. Finally, he declared himself the “Messiah of the God of Jacob” and set a date for the final Redemption: 15 Sivan 5426 (1666).

This “Messiah” continued violating Jewish law. He secluded himself with his first wife, who had married someone else, and promised various women that he would liberate them from the curse of Eve and from their husbands’ subjugation. He deposed Izmir’s rabbi, Aaron Lapapa, and replaced him with the eminent halakhist Rabbi Hayyim Benveniste. He also went to the khadi and slandered his detractors. And he arranged a magnificent ceremony at which throngs declared him the Messianic king, and he, in turn, abolished the fast of the Tenth of Tevet (which, according to Jewish tradition, is indeed to be discontinued in the Messianic era). His followers were a force to be reckoned with, instituting a reign of terror against anyone who dared disagree with their redeemer.

Significant differences of opinion arose in Izmir. The bulk of the city’s rabbis could not accept a Messiah who placed himself above the Torah and its commandments. In other communities as well, the scholarly elements and local leadership were deeply divided, but the bulk of the tradesmen and the poor were swept away by the tidings of Redemption.

Nathan began wandering among the various communities, gaining Sabbatean recruits. Even those rabbis who rejected his message refrained from doing so openly, effectively placing themselves on the fence. The enormous spiritual awakening and messianic expectations encompassed most of Europe, North Africa, and the Mediterranean. Letters described amazing miracles: in Amsterdam, for example, it was said that Shabbetai Tzvi had predicted when certain people would die, had forecast a day of darkness and hail, and had lit a huge bonfire and passed through it three times unscathed.

From Prison to Palace

In Izmir, all commerce ceased. The whole city was in turmoil, and every day was like a festival. The streets were filled with great processions, while at home there was feasting and merriment. Many immersed daily in the sea, even in the cold winter, and shouted in the streets, “Long live the king messiah! Long live Shabbetai Tzvi!”

Enormous excitement swept the capital. Letters and rumors inflamed the masses and sparked social upheaval. Community leaders full of misgivings lest the events be interpreted as a revolt against the Turkish authorities, feared that tragedy might ensue, endangering many lives.

The turning point came when the Turkish government decided to arrest the “King of the Jews” on suspicion of inciting to rebellion. Shabbetai Tzvi sailed from Izmir en route to Constantinople, but as he passed the Dardanelles, two ships intercepted him. He was brought to trial before the grand vizier, Ahmed Köprülü, but although the expected penalty was death, the official had been impressed by the absence of any military and political effort on the suspect’s part, indicating that he was no threat to the government. Shabbetai Tzvi’s charisma and charm also influenced the grand vizier, and he decided to settle for a term of imprisonment. Köprülü was even prepared to release him, in return for a large ransom, but Shabbetai refused, claiming that within a few days great things would happen.

After about two months in prison, Shabbetai Tzvi was transferred, on the eve of Pesach, to the Gallipoli fortress in the Dardanelles. On his arrival, he slaughtered a Paschal lamb and fed his followers the forbidden helev. They referred to his new location, where he stayed during the spring and summer of 1666, as Migdal Oz, “Tower of Strength.” The fortress soon ceased to function as a penitentiary. The cupidity of the Ottoman commanders, and the willingness of Jews the world over to contribute enormous sums to the Messiah, turned the prison into a palace. The guards happily allowed the masses of visitors to meet with their Messiah, for an appropriate fee. Shabbetai Tzvi was dressed in regal garb, and the whole complex was filled with “royal bed linen, pillows, and featherbeds, and all manner of gifts.” Shabbetai Tzvi sat in his palace, accompanied by his wife, Sarah, who had joined him, while Jewish scholars from the four corners of the earth made pilgrimage to him in order to look upon his glorious countenance, to hear his intoxicatingly beautiful singing, and to debate matters of Kabbala and other wisdoms. One eyewitness report tells of seventy Jewish virgins, daughters of his Believers, garbed in splendid raiment who served him and his queenly wife.

Prior to the fasts of the Seventeenth of Tammuz and the Ninth of Av, Shabbetai Tzvi sent a letter to his countless followers:

The first-begotten and only Son of God, Shabbetai Tzvi, Messiah and Redeemer of Israel, to all the sons of Israel, Peace!

Since we have been deemed worthy to behold this great day, a day of Redemption and Salvation for Israel, and the fulfillment of God’s word and promise by the Prophets and by His beloved Son – your lament and sorrow must change into joy, and your fasting into merriment; for you shall weep no more, O sons of Israel.

In the eyes of the faithful, Shabbetai Tzvi had attained the status of a god.

Nehemiah and the Downfall of Shabbetai Tzvi

Toward the end of the summer, one Nehemiah Hakohen, a kabbalist from Poland, paid a fateful visit to Shabbetai Tzvi. Nehemiah was mysterious. Some considered him a madman, while others saw him as a great mystic devoted to purifying himself through exile. In any case, Nehemiah met with Shabbetai Tzvi and challenged his messianic claims. He spent three days with him in fantastic theological debate – a debate between two messiahs. Nehemiah saw himself as Mashiah ben Yosef and was prepared to view Shabbetai Tzvi as Mashiah ben David, but he maintained – based on rabbinic tradition – that Mashiah ben David could not be revealed before the appearance of and wars fought by Mashiah ben Yosef.

Shabbetai Tzvi opened numerous religious works, of which there were plenty at Migdal Oz, and revealed many kabbalistic secrets, but Nehemiah would not relent, and demanded that reality conform to the plain meaning of the midrashic text. The debate grew heated. The two messiahs slept little and ate little, but they argued at length. Those present were hard-pressed to determine who had the upper hand, but suddenly Nehemiah rose to his feet and shouted at Shabbetai Tzvi: “You say you are Mashiah ben David, but would that you would leave the people of Israel alone and let them be as they were previously, rather than bringing them to the point of the sword through falsehood and lies. There is no truth in you. You are but a scourge of Israel, deserving of death as an inciter to idol worship!”

Nehemiah abandoned the debate; he applied to the grand vizier and asked to convert to Islam. Furthermore, he claimed Shabbetai Tzvi had declared himself the Messiah and had thus revolted against the Sultan. On 16 Elul, Shabbetai was tried before the Turkish sultan. During the swift trial, he denied being the Messiah. He was then given a choice: to be tortured to the death, or to convert. Shabbetai chose to live, and to accept Islam, and took the name Mohammed Effendi.

“The House of the Talmud,” as it is still called by Sabbateans, in Ulcini, Montenegro, where Shabbetai Tzvi supposedly spent the last years of his life of imprisonment

Shabbetai Tzvi’s most devoted followers refused to come to their senses. Hundreds of families converted to Islam in the wake of his conversion; others remained Jewish but waited for him to return, convinced that his actions reflected some deep secret. Nathan of Gaza explained that the conversion to Islam was part of the mystical work of “raising the sparks of holiness” in order to advance the Redemption. But the bulk of the Jewish people remained in crisis. From the heights of messianic expectation, they plunged into deep depression and disappointment.

One Messiah, seven graves. Three of them, including this one, are in Ulcini, Montenegro

The Sabbatean movement survived another century or so, in various incarnations, and continued to influence the Jewish communities of Europe. Famous debates ensued, there were further cases of false Messiahs, but no-one would succeed in rousing the Jewish world to a pitch of redemptive frenzy such as that induced by the apostate, Shabbetai Tzvi.